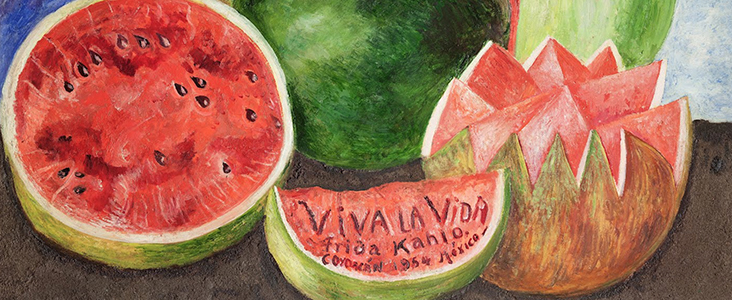

Frida Kahlo: Viva La Vida

“Feet – what do I need them for if I have wings to fly?”

Frida Kahlo is a timeless icon, a great storyteller who weaved personal tragedy with fantasy and Mexican folklore to produce enduring images that speak of the universal human condition. In her lifetime her stunning, exquisitely detailed paintings seldom sold, yet today she is recognised as the first female artist to reveal with such ripe candour her own world of suffering, which is perhaps why her art reaches such staggeringly high prices at auction today. Driven by an urgent desire to create, Kahlo wrote, “I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.” In her final painting, capturing juicy watermelons bursting with pink and green vibrancy, she inscribed the words “Viva la Vida” (Long Live Life), a parting message that, along with her art, would exert a powerful and lasting influence on generations to follow.

Kahlo was born to half-German, half-Mexican parents and raised in Mexico, in a family home known today as The Blue House or Casa Azul. As one of four sisters, she later referenced her childhood as “surrounded by women”, although she was incredibly close to her father, an architectural photographer. Kahlo was 3 years old when the Mexican Revolution began, remembering a childhood filled with gunfire and street violence. At the age of 6 she contracted polio, leaving her bedridden for 9 months, an illness that caused her right leg and foot to grow thinner and smaller than the left, which she would cover with long skirts for the rest of her life.

On her recovery Kahlo’s father encouraged her to take up sports to build up her strength; she took up various activities including football, swimming and even wrestling, an unusual activity for girls at the time. She later remembered, “My toys were those of a boy: skates, bicycles.” The artist’s father also taught her photography skills, including how to retouch and colour printed photographs, and asked one of his friends to give her drawing lessons.

In 1922, age 15 Kahlo began attending the renowned National Preparatory School in Mexico City, one of only 35 female students in the whole school. Her outspoken confidence and charismatic, mischievous spirit soon made her stand out above the crowd. It was here that she first met Diego Rivera, the famous Mexican muralist, who had been commissioned to create an artwork on the school campus and Kahlo would often play tricks on him, rubbing soap on the steps he worked on or stealing his food. Rivera was struck with the young Kahlo, later recalling her “unusual dignity and self-assurance, and … a strange fire in her eyes.”

The ambitious young Kahlo planned to become a doctor, studying biology, zoology and anatomy, inadvertently learning skills that would later come to inform her paintings. She fell in with a left-wing, political collective known as the “Cachuchas” who protested against the violent armed struggles they witnessed in the streets of Mexico City as the Mexican Revolution wore on; included in the group was Alejandro Gomez Arias, Kahlo’s first love. On a fateful bus trip home from school with Arias a tram collided into them and Kahlo was seriously injured as a broken metal handrail jammed into her hip, fracturing her pelvis and spine and impaling her womb. So severe was Kahlo’s accident that she had to spend a month in hospital undergoing a series of operations, where she feared she might die, telling Arias, “In this hospital, death dances around my bed at night.”

On return to her parent’s house Kahlo was bedridden for 3 months and had to wear a plaster corset to hold her spine together, while a lingering chronic pain from the accident would haunt her for the rest of her life. But tragedy made room for progress; as a captive invalid Kahlo found freedom through art, later remembering, “Without giving it any particular thought, I started painting.” Art became a vital spark of life that aided her recovery, which her parents encouraged by making her a special easel she could use in bed, bringing her paints and brushes and attaching a mirror to the end of her bed so she could paint her image on canvas. She later wrote, “I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best.” Her paintings from this time revealed an intense period of introspective self-reflection as she considered the impact of her near-death experience on her psychological state of mind.

As she gradually recovered Kahlo became involved in politics again – she re-joined the Cachuchas and became an active member of the Mexican Communist party with her friend, the photographer Tina Modotti. Through Modotti’s acquaintance Kahlo met Rivera again, who was enchanted by her “fine nervous body, topped with a delicate face”, likening her distinctive eyebrows to “the wings of a blackbird, their black arches framing two extraordinary brown eyes.” Kahlo was equally taken with Rivera, whose unbounded creativity and knowledge fascinated her, and she invited him to critique her paintings.

Over the next year Kahlo and Rivera formed a romantic relationship, though they were an unlikely pairing, he being 21 years older, already previously married twice, with a reputation as a womaniser, and significantly larger than the elfin young Kahlo. When they married in 1929 Kahlo’s mother regretfully described their relationship as a “marriage between an elephant and a dove.”

Throughout the 1930s Kahlo adopted indigenous Mexican clothing as her signature style, particularly the traditional clothing of the powerful, matriarchal Tehuana women which her mother had worn as a child, including voluminous skirts featuring panels of hand-made lace, multi-layered huipil tunics and lavish, theatrical headpieces. Friend Edward Weston wrote about her, “People stop in their tracks to look in wonder.” In her paintings she portrayed herself wearing the same clothing, celebrating flamboyant, tropical colours and intricately hand-woven patterns.

Kahlo travelled with Diego across the United States, following where his commissioned murals took him, but she grew increasingly homesick. Through her painting she explored these emotions, as seen in her Self Portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States, 1932, portraying Mexico as a lush, fertile landscape beyond the industrial smog of the city. Painfully direct autobiographical content also began to appear; she was desperate for a child, but after suffering a series of miscarriages it became increasingly clear her bus accident had left her unable to remain pregnant, a realisation that sent her into deep wells of depression, particularly after her mother died. In Henry Ford Hospital, 1932 Kahlo is naked, vulnerable and alone, bleeding onto her bed while haunting references to babies surround her. Rivera’s increasing infidelities only served to increase her feelings of isolation.

By 1933 Rivera and Kahlo had returned to live in Mexico on Kahlo’s request, but she wrote to a friend that Diego was resentful of the move and the negative impact it had on his career, saying he “thinks that everything that is happening to him is my fault because I made him come (back) to Mexico…” For their new home in the San Angel district of Mexico City the pair commissioned a new build from architect Juan O’Gorman, a house divided into two, so they could have separate wings joined by a bridge. But when Rivera had an affair with Kahlo’s younger sister Cristina, she was so devastated she chopped off all her hair and moved to her own apartment, a moment captured later in Self Portrait with Cropped Hair, 1940. Kahlo also began having extra-marital affairs, including brief dalliances with sculptor Isamu Noguchi and Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, while continuing a longer on-off relationship with Hungarian photographer Nickolas Muray.

Towards the end of the 1930s Kahlo’s paintings became ever more technically skilled and she sold a series of paintings to actor and art collector Edward G. Robinson, writing of her new found financial freedom, “This way I am going to be able to be free, I’ll be able to travel and do what I want without asking Diego for money.” Kahlo held her first New York solo exhibition in the same year, to rave reviews, travelling without Rivera. In 1937 she was photographed by Toni Frissell for American Vogue, with one arm raised in triumphal defiance. Buoyed up by her success, she travelled on to Europe in 1939, mingling and exhibiting her work with the Surrealists in Paris. In a letter to Rivera, Picasso expressed his deep admiration for her painting, writing, “Neither Derain, nor I, nor you are capable of painting a head like those of Frida Kahlo.” On her return to Mexico, Diego had begun an affair with another woman, and the pair decided to divorce.

Kahlo returned to her family home at the Blue House following their separation, where she worked on several of her largest paintings ever made, with the determination to achieve financial independence, including The Two Fridas, 1939. One year later Kahlo and Rivera had realised that despite the infidelities they could not live without each other, and were remarried in San Francisco in 1940.

Kahlo’s health began to deteriorate in the 1940s, although her career continued to flourish and she never lost her vivacious passion for life. With Rivera they hosted raucous evening events, where, as Kahlo’s stepdaughter Guadalupe Rivera remembered, “Frida’s laughter was loud enough to rise above the din of yelling and revolutionary songs.” Her artwork gained critical acclaim through a series of international exhibitions and during this period she produced some of her most iconic works of art, including the world famous Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Humming bird, 1940 and the heart-breaking The Broken Column 1944, which illustrates the stark horror and suffering of her spinal injuries. She also took on teaching work in Mexico, amassing a group of followers who became known as “Los Fridos,” telling her students, “It is necessary… to learn the skill very well, to have very strict self-discipline and above all to have love, to feel a great love for painting.”

In the 1950s Kahlo endured a series of painful operations on her spine, foot and leg and 1953, following a severe infection she had to have her right leg amputated below the knee. When her first solo exhibition in her beloved Mexico City opened she was still recovering from her operation, but determined to soldier on she was brought to the event in an ambulance, while a decorated bed was set up in the gallery for her to lie on. Despite her failing health, in the final years before her death Kahlo remained a dedicated leftist, attending various anti-nuclear demonstrations and infiltrating political ideas into her art. Her life was cut tragically short at the age of 47, after she suffered a pulmonary embolism. Following her death, the heart-shattered Rivera locked away thousands of Kahlo’s personal, intimate possessions in the Blue House, instructing a friend to keep them hidden until 15 years after his death.

The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Myself, Diego, and Señor Xolotl / Frida Kahlo / 1949

Since her death, Kahlo’s reputation has grown exponentially, achieving an international reputation that has rippled through into the worlds of art, fashion and literature. Along with major art retrospectives, various international exhibitions have been staged that celebrate her inimitable and instantly recognisable sense of style, influencing figures as various as Jean Paul Gaultier and Madonna, while her tumultuous love life has been a source of ongoing fascination with writers and art historians alike. Today her Blue House has since been converted into The Frida Kahlo Museum, dedicated to her life and work, revealing many of the fascinating secrets Diego tried to hide during his lifetime, while their shared home, the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo House Studio Museum, houses many of their most famous paintings.

Kahlo’s ability to achieve worldwide recognition across disciplines is almost unheard of within the art world, as writer Susana Martinez Vidal points out: “… a half indigenous, who didn’t belong to a first-world country, who wasn’t in show-business (she wasn’t an actress, singer or dancer) managed to become one of the most iconic women of the 20th century, next to Marilyn Monroe, Jackie Kennedy and Maria Callas.” In 2002 she was immortalised in a biopic film, played by Salma Hayek, which revealed how intertwined her art, life and style really were. Janet Landay, curator at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, surmised: “Kahlo made personal women’s experiences serious subjects for art, but because of their intense emotional content, her paintings transcend gender boundaries. Intimate and powerful, they demand that viewers – men and women – be moved by them.”

One Comment

Susan Johnson

thank you! love your written offerings.