Beyond the Studio: Serge Diaghilev’s Artistic Collaborations

Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev was a formidable giant of the 20th century, fusing ballet with cutting-edge drama, music and art. But by far the most influential aspect of his legacy has to be his ‘Artist Programmes’, in which he invited the world’s leading avant-garde artists to produce daring Cubist, Surrealist and Neo-Primitive sets and costumes for his ballet productions. Through these surprising and unexpected collaborations Diaghilev was able to completely transform the once classical, traditional art form of ballet into a site for radical experimentation, while giving artists the freedom to move outside the studio into an entirely new creative playground. “There is no interest in achieving the possible,” said Diaghilev, “but it is exceedingly interesting to perform the impossible.”

Diaghilev began his career in St Petersburg where he founded a fine arts magazine and curated a huge survey exhibition in Russian portraits. Known for his precocious confidence and winning charm, he earned a wide band of followers from early on. In 1906 Diaghilev moved to Paris and just three years later he had founded his ballet company The Ballets Russes alongside a talented and renowned band of fellow Russian emigres including the choreographer Michel Fokine, dancer Vaslav Nijinksy and the composer Igor Stravinsky. Russian painter Leon Bakst was the first artist to create décor for the Ballet Russes, producing stunning oriental costumes and backdrops for the company’s incantation of Cleopatre in 1909 featuring dazzling bejewelled colours and the swirling linearity of Art Nouveau.

Parisian audiences were intoxicated by the colour, sensuality and exoticism of the Ballets Russes, and early success led Diaghliev to establish year-round performances across Europe and America, spreading the company’s reputation far and wide. Charismatic and entrepreneurial, Diaghilev networked with the Parisian avant-garde and forged a series of collaborations with artists that were unlike anything anyone had seen before. “Surprise me!” said Diaghilev to any creative who approached him with a proposal, encouraging them to bring the most daring and provocative ideas to the table. Contemporary choreographer Christopher Wheeldon observed how these collaborations reinvented the experience of ballet, creating what he called “the idea of music and art and movement coming together to create a whole artistic experience.”

Natalia Goncharova, Seahorse costume from Sadko, Museum Rolf de Maré Stockholm, 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Adagp, Paris

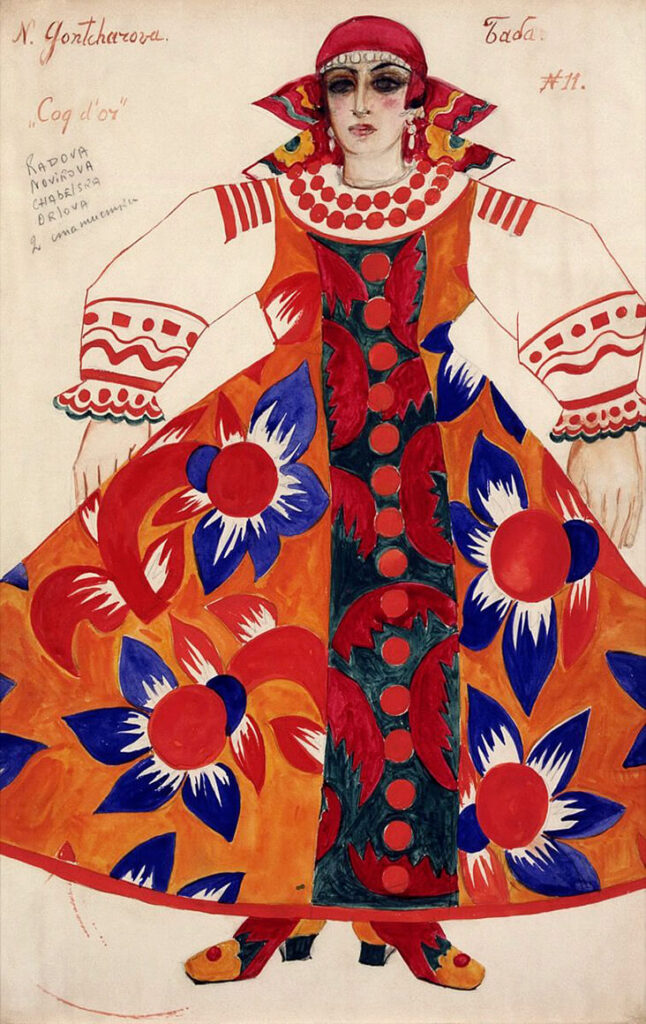

Working with Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes was transformative for artists too – taking ideas outside of the studio and into living, breathing three-dimensional forms was a liberating process for many, while the temporal nature of their backdrops and costumes meant artists could experiment with ideas they might not have otherwise dared to produce. Russian artist Natalia Goncharova worked with Diaghilev on the costumes for Le Coq d’Or in 1914, merging the iconography of Byzantine art with angular, Cubist forms, discovering profound ideas related to Neo-Primitivism that would feed back into her paintings and prints.

Natalia Goncharova, Peasant woman costume design for Le Coq d’Or, 1914, © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Courtesy of the Tate

From 1916 onwards Pablo Picasso worked with Diaghilev on six separate ballet productions, seizing the opportunity to expand his studio practice out into an entirely new arena, revealing some of the most adventurous work he would ever make. Through his work with the Ballets Russes Picasso’s style gradually moved from abstraction back into representation, informing developments in his wider artistic practice. Similarly, French painter Sonia Delaunay befriended Diaghilev in the early 20th century and through her stunning work on the production of Cleopatre for the Ballets Russes in 1918 she was able to consolidate divergent ideas in movement, costume, colour and abstraction.

A poster with a Cocteau drawing of the dancer Nijinsky, for the company’s 1913 season. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

All this experimentation was not without its risks; critics accused Diaghliev of turning the ballet stage into an art gallery, while he was known for going way over budget and struggling to stay financially afloat. But since his untimely death in 1929 Diaghilev has had a profound and far-reaching influence on the nature of ballet, inspiring countless choreographers and ballet companies worldwide to take a more inclusive, interdisciplinary and progressive approach to the much-loved theatrical art form. Following on his example, leading artists continue to experiment with the stage as a platform for their studio practice, from Olafur Eliasson’s visual concepts with the Manchester Opera House to Howard Hodgkin’s painted sets for Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London. “Ballet suddenly became electric under Diaghilev,” observes Wheeldon, “it became cutting-edge, it became daring and rich.”

Feature Image: Natalia Goncharova, Set design for the final scene of The Firebird, 1954. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Courtesy of the Tate.

2 Comments

Christina Daily

Once again Rosie has left us with a lovely look at another creative person who had vision and imagination. The colorful and fantastical coustumes for Diagihilev ballets are fabulous. thanks!

Rosie Lesso

Hi Christina, thanks for the positive feedback – great to hear you enjoyed the article!