A Celebration of Life: Fabric in Realist and Impressionist Art

Realist and Impressionist art is a celebration of life, portraying real people in simple scenarios like caring for children, working the land, picnicking in the park or enjoying quiet moments of solitude. The fabric that breezes through this art is also refreshingly normal – crisp white cotton puffs into voluminous sleeves or bulbous, corseted skirts, fresh floral prints adorn Victorian home furnishings and rugged hessian is slung loosely over the shoulders of flushed young farm workers. This fabric is described with fluid, expressive brushstrokes, capturing clothing as a flurry of movement that passes with bodies through space.

French 19th century Realism was a watershed moment in the history of art, a time when artists broke away from the prescribed doctrines of the art establishment to forge their own path. Their art was a deliberate rejection of earlier, idealised styles, instead connecting with the plight of ordinary working people. They zeroed in on subjects once deemed not fit for art, such as domestic interiors and farm workers, painted with subdued, pared back colour schemes to connect them with the normality of everyday life. Clothing in rustic, earthy tones also allowed figures to merge into one with the land around them, emphasising their close relationship with the environment.

French painter Jules Bastien-Lepage was fascinated by the farm workers of his local village in Damvillers, particularly the spritely children who were sent to work outdoors from a young age. His sympathetic portraits capture the determined spirit in these youngsters on the brink of adulthood, whose faces hold hidden layers of mischief within. Pas Meche, 1882 is perhaps one of his best-known portraits, conveying a barge boy caught in a moment of respite, casually leaning into a relaxed contrapposto (the title, Pas Meche translates as “doing nothing”). His rough, worn out, dirty and oversized clothes tell a story of poverty and struggle, but they also blend him into one with the surrounding land, suggesting a life of outdoor adventure and play.

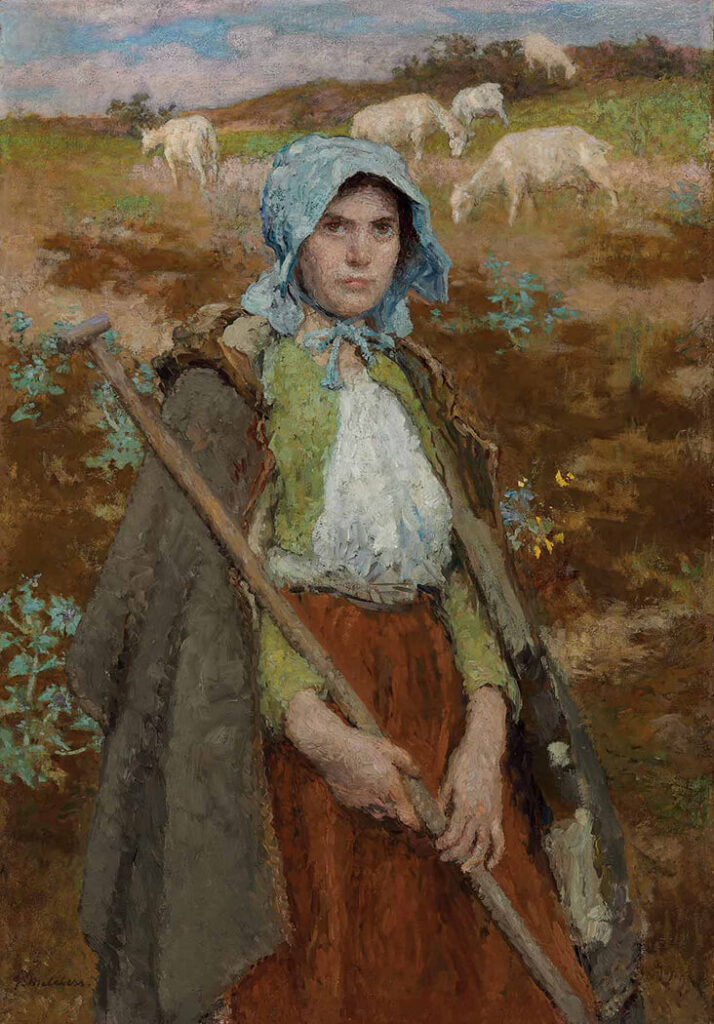

The American painter Gari Melchers trained in France in the late 19th century before settling in the Netherlands, making his name with genre scenes of day-to-day life such as churchgoers, milkmaids and villagers. Like Bastien-Lepage, fabric was a potent tool that allowed subjects to become one with their surrounding scenery, as demonstrated in The Goatherd, where the young woman’s simple, durable and hard-wearing clothing is painted in the same autumnal shades of rust, ochre, green and white as the field beyond.

Impressionist styles that emerged out of France in the late 1800s, before spreading throughout Europe and the United States also focussed on observations of everyday life, but with a looser, more rapid style of painting, and brighter, fresher colours. Vivid, patterned swathes of luminescent fabric weaves through much Impressionist art, particularly that by women painters of the era whose lives were predominantly played out in domestic settings.

American-born, French painter Mary Cassatt was entranced by the patterns of Victorian fabric, exploring how they could bring dynamism and energy into her lively interior scenes. One of her most celebrated paintings, Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878 is a dazzling array of oceanic blue furniture, speckled with tropical floral patterns that shimmer across its surface. This vivid blue sweeps through the shadowy background before encircling the young girl collapsed into its soft cushioning, drawing our eye towards her intricate lace dress and tartan sash. Similarly, Child’s Bath, 1893 is dominated by the fresh vitality of the mother’s striped dress, sweeping from left to right across the scene like a shaft of light against a warm, neutral background.

Fabric undoubtedly informed the art of Cassatt’s friendly rival Edgar Degas, particularly in his portrayals of spirited young dancers, which he regularly painted and drew during backstage rehearsals. In the pastel study Four Dancers, 1903, the group of girls are a flurry of brimming, nervous energy, shifting to and fro in puffy pink and blue tutus the texture of candy floss, with waists pulled neatly into taut yellow bodices.

American Impressionist Lilla Cabot Perry drew on the language of her French contemporaries, and she often enjoyed situating her subjects in outdoor settings so she could capture the fall of white light across their crisp, cool clothing. In Girl Reading a Book, the young woman’s white dress catches ripples of blue, green and lilac from the surrounding landscape into its folds and creases, as if soaking the fresh, bracing atmosphere deep into its tightly woven surface.

Leave a comment