FS Colour Series: Willow inspired by Paul Nash’s Hazy Dawn

Pale, hazy tones of dawn swept across Paul Nash’s dreamy scenes, suggesting a place where all is hushed and still. The warm, pastel green of WILLOW linen was one of his recurring colours, invoking the cold light of frost-bitten grass, whispery strands of freezing fog or dreamy forms that seem to fade into distant, heavenly skies. Nash’s early landscapes captured the light and life of real places around him, but towards his later career representation gradually fell away, making room for a personal language of Surrealism that reflected on the deeper meaning of life. Even so, the soft colours of the early morning British landscape stayed with him, taking on mystical, imaginative properties. “My love of the monstrous and magical led me beyond the confines of natural appearances into unreal worlds,” he wrote.

Born in Kensington, London in 1889, Nash moved with his family to the Buckinghamshire countryside when he was just three years old. The nature around him was an endless fountain of inspiration, particularly the biomorphic trees near his house, which he compared to “urgent females with fantastic hats.” Though he struggled with academic subjects, his early aptitude for drawing eventually led him to study art at Chelsea Polytechnic, the London County Council School of Photo-Engraving and Lithography and the Slade School of Art, where he studied alongside an up and coming generation of artists including Stanley Spencer, David Bomberg and Dora Carrington.

Following a conflict with one of his tutors Nash left his studies at the Slade early, retreating into the Buckinghamshire countryside to make art in isolation. Nash’s younger brother John had begun painting by the 1910s and the two supported one another’s endeavours, often exhibiting their landscapes together. Nash’s early work was often made in watercolour, combining light washes of colour with carefully drawn areas of linear detail, as seen in the fresh, pastel toned The Garden at Wood Lane House Iver Heath, 1912. A wide expanse of sky opens out suggesting the brightness of a new day, while minty green leaves seem to rustle here and there. A strip of warm pale green as fresh as a new apple breaks out across the horizon, bringing warmth and spreading glowing radiance through the scene.

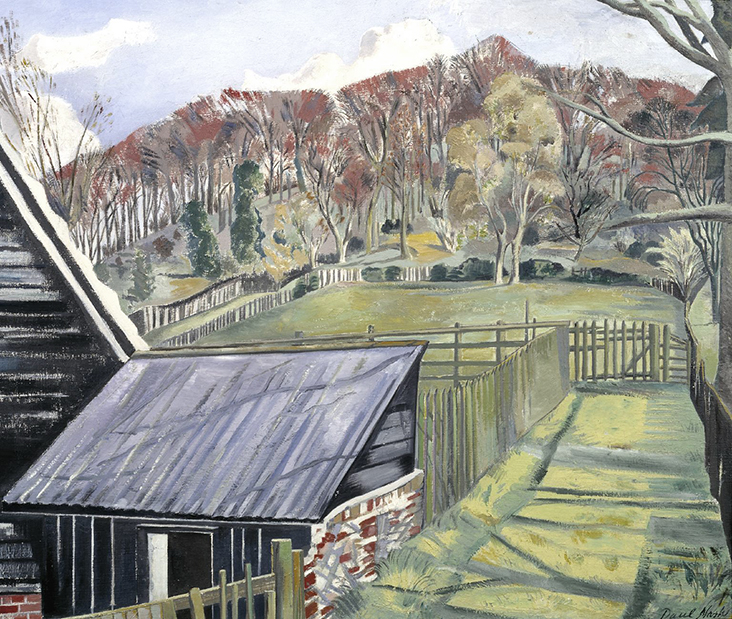

During the First World War Nash married Margaret Odeh, a Women’s Suffrage campaigner, but he was called to the front line to work as war artist shortly after their union. Though Nash found the experience of war deeply traumatic, his potent, emotional drawings and paintings received much critical praise for their “dignified rage”, helping secure him a wider reputation as a leading British artist. Though his post-war paintings were less innocent, there was a haunting sense of drama that seemed to capture the British imagination, leading to an ongoing series of exhibitions and commissions. In the landscape painting Behind the Inn, 1919–22, Nash captures the rugged Buckinghamshire countryside in the early morning light; a sea of pale greens weave in and out of the light and seem to bristle in a cold breeze, while craggy buildings in the foreground suggest a quiet trace of human presence.

By the 1930s Nash’s language was gradually turning abstract and distorted, although loose references to the mystical, spiritual properties of the landscape remained. Taking inspiration from the Surrealist languages of Max Ernst and Pablo Picasso, Nash looked inward to the realms of dreams and the subconscious mind for subject matter, commenting, “I believed that by a process of what I can only describe as inward dilation of the eyes I could increase my actual vision.” In Mansions of the Dead, 1932, an imaginary scaffold floats in a cloud filled sky, a site Nash called “aerial habitations where the soul like a bird or some such aerial creature roams at will.” Here billowing clouds form feathery pillows, falling around a light golden-green framework that shines with such pale brilliance it could be the gateway to heaven.

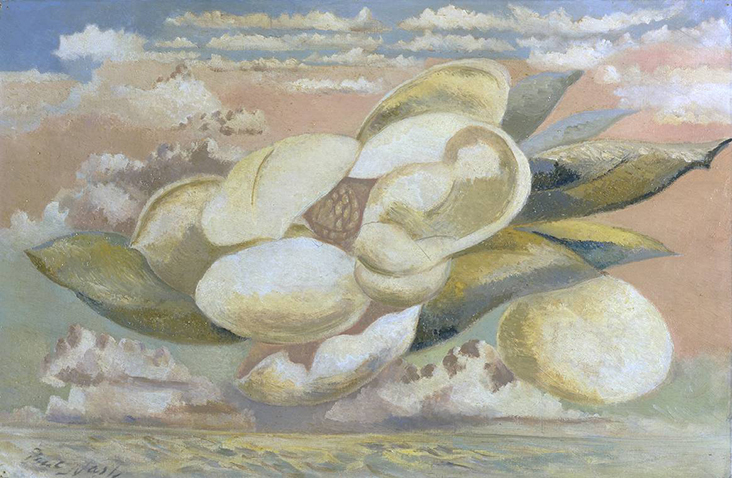

Flight of the Magnolia, 1944 was made nearly a decade later but the same ethereal, spiritual qualities remain, conveyed through limited pastel tones. A magnolia flower floats in an imaginary, early morning pink sky, while dusty greens tinge the tips of leaves, falling into earthy tones that suggest an endless cycle of growth and regeneration. Nash’s first biographer, Anthony Bertram aptly described the painting as a potent symbol of the entrance into the after-life, calling it “the last flight of the soul … in the form of a flower.”

Leave a comment