Elsa Schiaparelli: The Shock of the New

“In difficult times, fashion is always outrageous.”

Italian designer Elsa Schiaparelli was a bold risk taker, one whose eccentric, flamboyant designs brought apparel in line with 20th century, avant-garde art movements including Dada and Surrealism. Recognised today as one of the most prominent and influential voices from the Parisian 1930s, 40s and 50s, Schiaparelli’s adventurous life was filled with scandal, controversy and public attention. She famously collaborated with cutting edge artists including Salvador Dali, Jean Cocteau and Christian Berard, pioneered new approaches to knitwear, couture and fashion aesthetics and dressed the rich and famous. The title of her compelling biography in 1954 was Shocking Life, alluding to the complexity of her tumultuous life, while she goaded everyone to follow her lead, coining the maxim, “Dare to be different.”

Born in Rome in 1890, Schiaparelli’s mother was an aristocrat and her father an academic who specialised in ancient Islamic culture. Growing up in the grand Palazzo Cortini, glamorous parties filled with socialites and intellectuals were the norm, and Schiaparelli was fascinated by the eccentric styles around her, particularly those of the Marchessa Casati, who once turned up to their home with a leopard on a diamond studded leash. Schiaparelli’s older sister was the more conventional beauty, who quickly ingrained herself into her parent’s lifestyle, while Schiaparelli was often left feeling like the outsider. In retaliation she became a rebellious spirit, pulling pranks to break apart the conventions around her, including running away for three days when she was six, stuffing flower seeds into her ears, nose and mouth to become ‘more beautiful’ and opening a jar of fleas during a lavish dinner party.

After leaving home, Schiaparelli initially followed her father’s footsteps into academia, studying Philosophy at the University of Rome. But with a desire for scandal burning inside, Schiaparelli published a collection of sensuous, erotic poetry titled Arethusa, which so shocked her parents that they sent her to a Swiss convent as punishment. After going on hunger strike, Schiaparelli was allowed to return home.

In a bid to escape a Russian suitor her parents had chosen for her, Schiaparelli took a job as a nanny in London, where she meandered around the city’s streets, soaking up the culture around her, while going to various museums and lectures. It was at a lecture that she met and fell in love with Count William de Wendt de Kerlor, who specialised in palm-reading, theosophy and the paranormal; she married him in a whirlwind romance and they moved to New York, where their daughter, Maria Luisa Yvonne Radha de Wendt de Kerlor, later known as Gogo Schiaparelli, was born.

In New York, Schiaparelli found work with Gaby Buffet-Picabia, the ex-wife of the French Dada artist Francis Picabia, who owned a boutique selling French fashion to New York. Schiaparelli was as fascinated by the intricacy and craftsmanship of the clothing as her employer’s social circle of brave, experimental Parisian artists, including Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. When her marriage folded following her husband’s infidelity, Schiaparelli followed Duchamp and Ray to Paris, taking her young daughter with her.

Initially Schiaparelli found work in an antique dealer’s shop, while her friendship with the social butterfly Buffet-Picabia opened doors for her in Paris, and she quickly became enmeshed with the lively artistic scene. In 1924 Schiaparelli visited Paul Poiret’s fashion house with a friend; although she was too poor to buy his clothes, Poiret allowed Schiaparelli to borrow some dresses from him for social events and the luxury and craftsmanship of his designs lit a spark in her that would become a flame. She began making her own clothing designs with determination, while maintaining a friendship with Poiret. By 1925, she had released her first design into the public, a black, hand knitted pullover, with a grey tromp l’oeil scarf motif. The work was made by a skilled group of Armenian knitters in Paris who Schiaparelli had befriended, employing larger numbers of the group when the sweater sales shot up. The radical nature of printing decorative details attracted attention from both public and press and her design became an overnight success, selling in the hundreds and appearing in French Vogue.

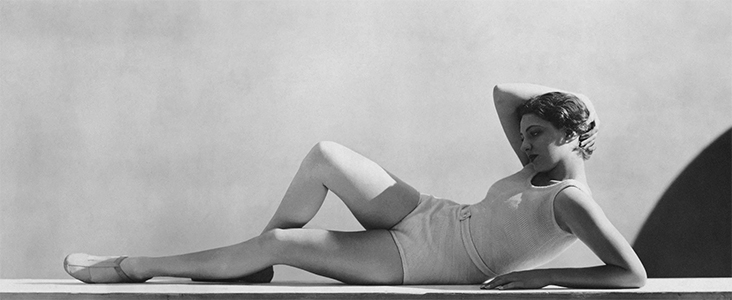

Riding on a high note, Schiaparelli began branching out into more adventurous designs which soon attracted attention and by 1927 she was ready to launch her own company, initially from her Parisian apartment. Tapping into the market for ready-to-wear fashion, particularly for women looking to break free from the constricted styles of the past, she labelled here brand Schiaparelli – Sportswear, specialising in a blend of haute couture style and sporty silhouettes. Popular designs included knitted swimsuits, beach pyjamas and tweed sportswear ensembles, with a focus on comfort and style.

The hat in the shape of an upturned shoe, on which Schiaparelli collaborated with Salvador Dalí / 1937

By the late 1920s Schiaparelli, now known by her friends as Schiap, had released her own perfume brand, and had earned a name for her quirky, striking sweater designs, incorporating abstracted, vibrant motifs into her designs inspired by Surrealist art, including fish, tortoises and skeletons in yellow, red and lime green. Various innovations first appeared in her designs during the 1930s, including visible zippers, jumpsuits and tailored, feminine evening jackets. This period also signalled the beginning of several successful collaborations with artists. With Surrealist painter and sculptor Salvador Dali, Schiaparelli introduced a series of outrageous designs including the macabre, all black Skeleton Dress with visible, protruding bones, the Lobster Dress, featuring a bold red lobster motif emblazoned across a simple white dress, and the Shoe Hat, transforming a simple heeled shoe shape into an elegant hat. She brought Jean Cocteau’s dreamy, whimsical drawings onto dress and jacket designs, introducing a Dada spirit of play and experimentation into the realms of fashion. Statement pieces that would make an impact like these became her calling card as she commented, “Never fit a dress to the body but train the body to fit the dress.”

Even so, there remained an emphasis on celebrating femininity in her most marketable designs, particularly her innovative use of the first built in bra, which she brought into her swimwear collection, and the endlessly flattering wrap dress that she introduced into the realms of haute couture. In 1931, Schiaparelli went a stage further with her split skirt culottes, causing a huge scandal and raising a media frenzy. In the 1930s women still rarely wore trousers, so to break the status quo put Schiaparelli on the map as a progressive radical who fearlessly took on the system. When tennis player Lili de Alvarez wore one of her split skirts at Wimbledon the world sat up and took notice.

Schiaparelli’s business was booming and by 1932 she had established huge premises over several floors and employed over 400 members of staff. Just a year later, she opened offices in London and New York and in 1934, became the first female fashion designer to appear on the cover of America’s Time magazine. The strength of her designs symbolised a new kind of feminine power which attracted some of the world’s most prominent and successful women, including Hollywood stars Greta Garbo and Katharine Hepburn. In 1937 Schiaparelli released her perfume Shocking, while bringing the colour she defined as “shocking pink” into her clothing designs, which would become a vital strand of her signature brand.

Throughout the Second World War, Schiaparelli worked tirelessly to keep her business running, designing comfortable clothing to be worn during air raids, such as the zippered jumpsuit with a maxipocket and the coat with built-in bag, injecting style into the darkest of times. Leaving Paris for New York for much of the war, Schiaparelli left her boutique in the hands of her trusted colleague Hubert de Givenchy, while some suspect she was working as a German spy, leading the FBI to keep her under close observation.

Following the liberation of Paris in 1945 Schiaparelli returned to the city once more, where she continued to push the envelope, inventing the first capsule wardrobe for the travelling woman, called the Constellation Wardrobe, weighing under 12lbs, including six dresses, three folding hats and a reversible coat.

Like many designers who made their name during the fin de siècle Schiaparelli’s business struggled to maintain its buoyancy during postwar austerity and she saw the fashion landscape around her shifting in new directions. Aged 63, she was ready to retire, and in 1954 she closed her company, choosing instead to focus on transforming her scintillating life story into a best selling book.

Although it would be over 50 years before the fashion house was resurrected by businessman Diego Della Valle, the seeds of Schiaparelli’s influence had already been sown across the fashion landscape and begun sprouting new forms. Her ability to blend the adventurous spirit of Surrealism and Dada into fashion remains her strongest legacy, one that continues to live on in the experimental shapes, forms and fabrics of Muccia Prada, Issey Miyake and Diane von Furstenberg. In 1934, Time magazine summed up her legacy, calling her “… madder and more original than most of her contemporaries, … Schiaparelli is the one to whom the word ‘genius’ is applied most often.”

One Comment

Vicki Lang

A strong powerhouse of creativity. Elsa Schiaparelli played her way and won.