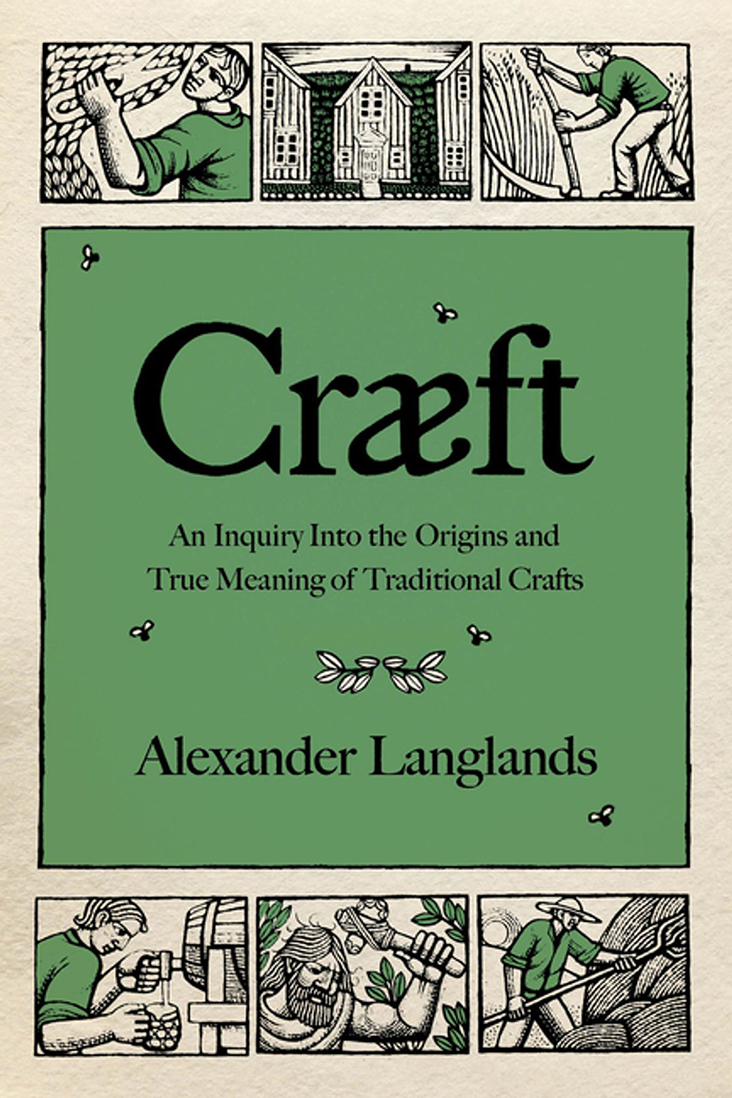

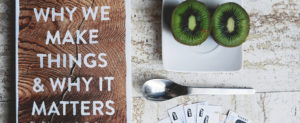

Book Review – Cræft: An Inquiry into the Origins and True Meaning of Traditional Crafts

Cræft, is written by a British archaeologist Alexander Langlands; who looks at Craft with a particular professional enthusiasm. Archaeology often uses craft as a way of interpreting a culture. Craft is the building block in the narrative of the past. Each chapter (there are 14 in total) investigates a series of tools and practices – from scythes to sticks; from digging to weaving. It provides a rich broth of interpretation by bringing the ingredients together in a historical mix – from Palaeolithic tools to contemporary shoe design.

The book opens with the word Cræft, and how this meaning has changed over time and continues to evolve. The Anglo-Saxons used the term with far greater nuance than today. Cræft was a skill of both hand and thought – think of a ‘crafty person’, rather than a maker alone.

Slithers of meaning have been stripped away over the centuries. The connections with intellect and mindfulness, over practical skill alone; have largely been forgotten or marginalised. It is this ‘almost indefinable knowledge or wisdom’ of craft which Langlands laments and reenergises throughout the book.

Written with a passion for the handmade and hand tools, it explores his admiration for the ingenuity of mankind. He calls himself a ‘Renaissance Man’ and the book is often driven by a boyish enthusiasm. His wife is never mentioned by name (the book is dedicated: ‘For Nicola’), but she follows in the flume of his passions: pottery, bee-keeping, thatching to name a few. Each ignited by the landscape and predicament he finds himself in. Thus, when he, or later, his family, move to a new home it will lead to his learning to thatch or the importance of wool: we learn how heating his home was an important by-product of wool production.

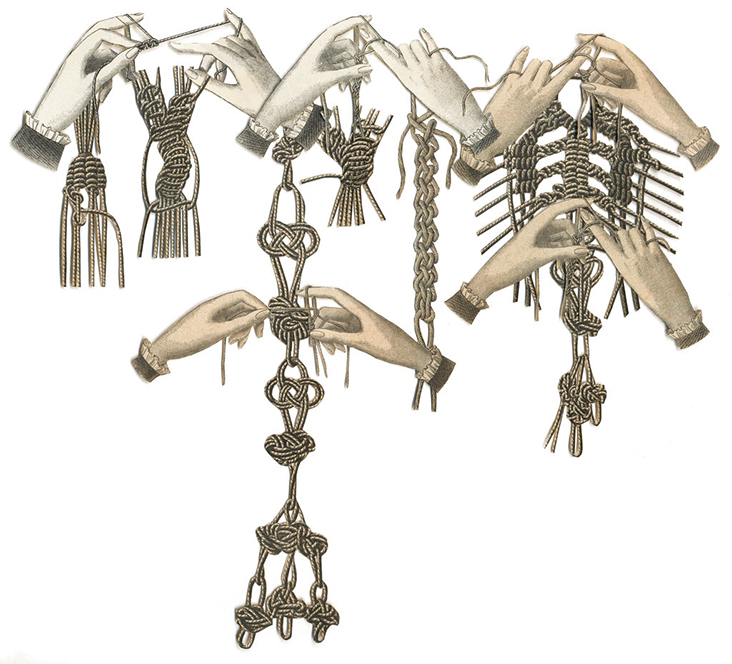

Each chapter captures the crossover in how skills are used across crafts: Weft and Warp and Under Thatch, capture the cross-fertilizations in making practice. How basket weaving can lead to cloth making for instance.

The book makes clear how craft, once defined as such, is always in tension with mechanical modernity. This tension is evident in the chapter about haymaking: Making Hay, captures the problematic nature of craft and industrialisation. And importantly, how we become detached from craft and craft making. Today: ‘western society is almost as removed from haymaking as we are from the fifth millennium BC’. In this context haymaking is a very good starting place to look at the critical relationship between making and industry. As he comments: ‘There is undoubtedly a cræft to haymaking’.

Like so often in this book, this chapter takes us on evocative sweeps of the landscape, as we swoop over the topography of the Cévennes region in France, and Britain too. Cévennes in France is ‘an area particularly celebrated for the continuous negotiation between man and nature’.

He uses the Scythe as an example of how craft reengages us back into the world of making – in this case hay-making – and he argues the popularity of the tool today, especially in America, is due to it making a stance against the reliance on fossil fuels.

Maybe it’s because of his background in archaeology but there is something earthy about this book, you are never far from the friable soil beneath our feet. From which springs the relationships between tools, craft and man. ‘Digging has obsessed me from an early age,’ he comments in the chapter The Craft of Digging.

He always looks at craft holistically. Craft is as much about time management and ensuring sound financial management as it is about the more romantic sense of the ‘handmade’. This is no more so than when he talks about the arts and crafts movement at the end of 19th Century. He acknowledges it was an ideological movement and not solely an aesthetic one. He also demonstrates that part of the failure of the movement was its non-engagement or abandonment of economics in relation to production. Thus, moving production to a countryside idyll for craft makers, separated it from its consumers: urban dwellers in London.

Countryside versus the City is a conundrum which has vexed craft makers ever since William Morris tried vainly to amalgamate the two. The issue has been alleviated in recent years by the Internet and outlets like Etsy. But this has only reinforced another thread to Langlands’ book – how we are increasingly detached from knowing and appreciating the skills in craft making. We consume Craft without appreciating the time and skills involved in its making.

In chapter Weft and Warp, he talks about the fashion industry being a conspirator in this phenomenon. Technological developments in cloth making – from cottage industry to the textile mills and factories of the 19th Century – lead to a separation from the skills of making. Its apotheosis is fast fashion today, which has ‘outsourced’ construction skills to countries outside of the USA and Europe.

It is important, he believes, to reengage with a broader understanding of craft and its influence on our day-to-day living. Langlands mentions our ‘illiteracy of power’: if we lose contact with the making-practices we forget the consequences or magnitude of industrial power which arrives with a ‘flick of a switch’.

Each chapter captures the crossover in how skills are used across crafts: for example Weft and Warp and Under Thatch, capture the cross-fertilizations in the making practices of both.

Throughout the book, Alexander Langlands entwines passion and critical commentary.

Langlands comments in the conclusion ‘Cræft is a form of intelligence…’ but in a world, which is suffering from overconsumption via industrialised production it ‘no longer feels all that intelligent in a world of diminishing resources and increasing environmental instability’ to continue to produce ‘things’.

Craft makers can again take up the mantle against consumption-for-consumptions sake.

We cannot all become makers but engagement with, and knowledge of, crafts, could allow us to develop a connection with the processes involved and to audit the things we consume.

As Langlands comments – ‘a new cræfty-ness is reqiured’ To be Mindful.

The book is beautifully illustrated throughout by Harry Brockway.

[Please note this post contains affiliate links and we may earn a commission if you make a purchase.]

3 Comments

Suzanne Raupp

My husband and I have read this book cover to cover. It is a must read for anyone who values craftsmanship and understands the real possibility of losing the knowledge and practice of these techniques due to the passage of time.

Elaine Rutledge

I am a craftsman of advanced age. Am at the part of my life that I am experiencing the spiritual element in what I do.

Vicki Lang

thank you for acknowledgement of some of the older crafts. Most have faded away.