A Brief Look at Colonial Attire.

The Colonial period had a particular style of dress that determined the types of garments worn. Styles would vary depending on the occasions and temperatures. Each Colonial citizen dressed according to their occupation, economic power, and social status. This is similar to other historical periods, in which your status was apparent through the appearance and style of clothing you wore.

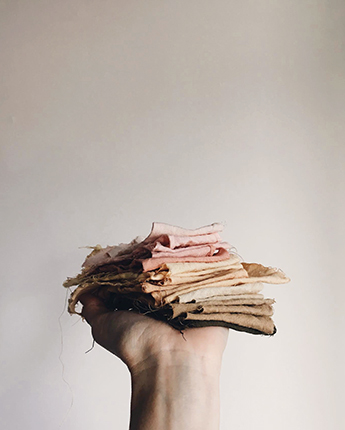

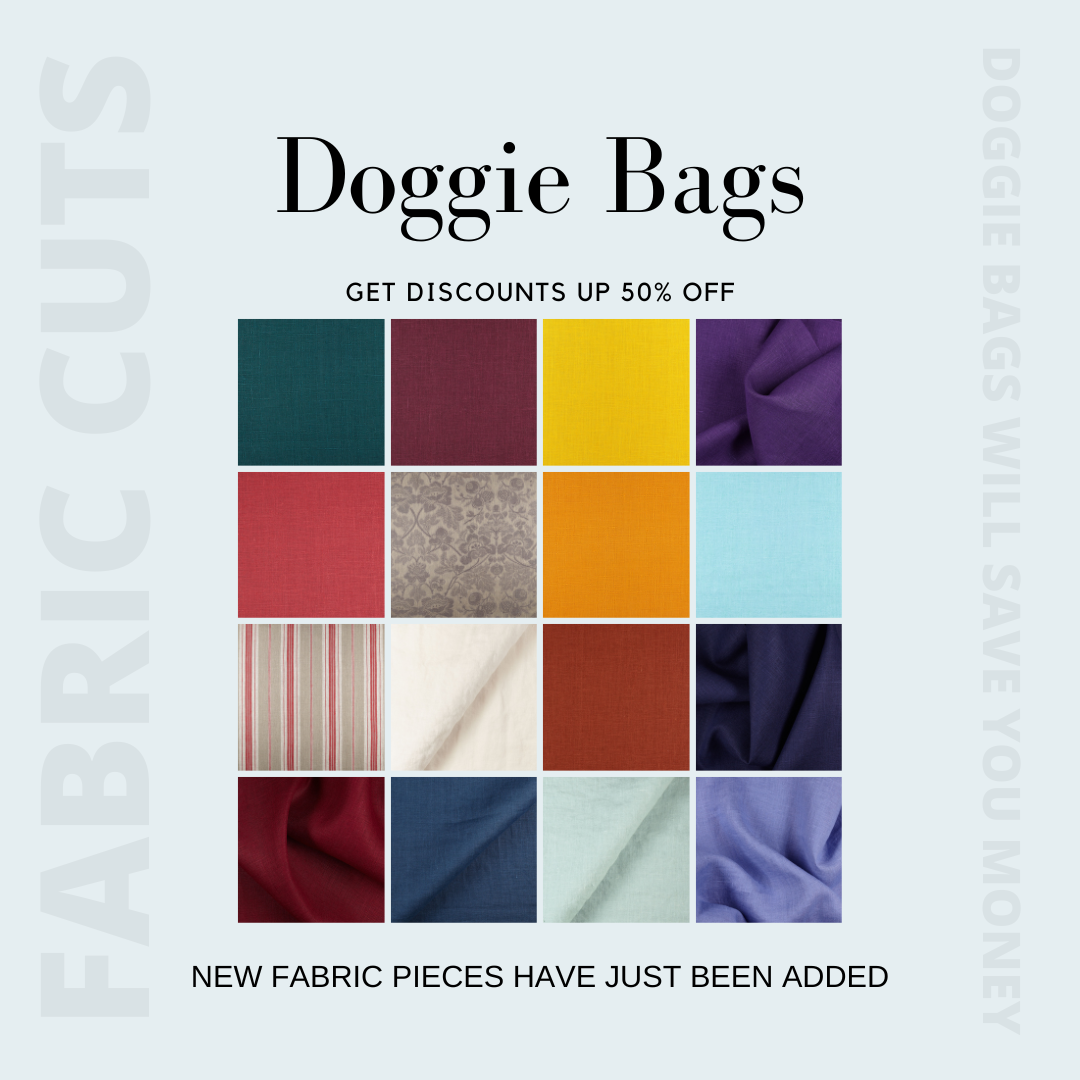

Those with greater wealth could afford more luxurious, imported materials such as satins, silks, and brocades. Colonists with less money to spare would instead use homespun linen, cotton, or wool cloths. These farming families represent a more common standard of living in the Colonial period.

There were also more customs dictating the appropriate type of dress for different occasions. The difference between formal and casual dress was much more significant than it is in most cases today.

Fashion trends existed during the Colonial period; and relied heavily upon styles brought back from Europe, and more specially London. Still in the midst of uniting their new country, most Colonists still sought to dress in the most up-to-date styles found in the European fashion capitals.

Today, we will explore the fashion of Colonial America. It is always interesting to discover more about the past and see how remarkably different we live today (or in this case, dress!). This is a great, quick read if you are interested in sewing or assembling your our Colonial outfit to dress up in too!

Everyday clothing had the same basic components of formal wear but were made of less elegant materials. Colonial wear for men, whether casual or formal, consisted of breeches, a shirt, a waistcoat and coat.

Men would wear a knee-length coat with fitted shoulders and narrow wrists over a high-collared shirt. A cravat, the forerunner to the modern necktie or bow tie, was tied around the neck. Breeches ended at the knee and were worn with stockings.

Informal clothing was worn by all men, regardless of their status, in order to cope with the hot summer temperatures. Linen and cotton were the fabrics of choice because of their light, airy nature. These easy to launder fabrics were perfect for everyday garments, such as stockings.

Casual unlined coats and light waistcoats were also made of cotton and linen. These were worn during the hot summer days instead of formal suits. Around the house or for casual meetings, a banyan or an informal robe was sometime worn. Although garments were made of lighter fabrics, men would still perspire a good deal. To hide any signs of perspiration, men would change their waistcoats during summer days.

Formal Menswear:

In the Colonial period, formal occasions required men to dress in suits. These suits were made of woolen broadcloth or silk, rather than breathable linen or cotton. They were embellished with accents such as ornate buttons.

Waistcoats were standard in formal attire as well. Formal menswear featured more luxurious styles that were not well-suited for everyday casual wear. These included striped breeches made of velvet, white blouses, and white stockings. These styles would have been uncomfortable in the heat, difficult to clean, and hard to maintain throughout the day.

No proper colonial man would dare forget to put on his powdered wig to complete his ensemble. After that, the only thing left to put on were your leather shoes that were, of course, gleaming with freshly polished metal buckles. Occasionally, a white linen stock was worn, tucked under the chin and fastened behind the neck.

Upper class gentlemen would order custom-tailored suits from London to keep up with the latest fashions. In this way, Colonists still look to Europe for style trends when trying to dress sharp. “Suits in ditto” were popular imported suits that had matching pieces. Men would wear these matching breeches and coat with an appropriate shirt and waistcoat.

Casual Clothing for Women:

During the Colonial times, casual attire for women were known as bed gowns. Bed gowns were worn daily and were made of loose fabric. The gowns were practical and comfortable enough for women to wear while performing their numerous household chores.

The main component of a day dress was a shift, or a garment shaped similarly to a plain long nightgown. This was made of linen or cotton so it was breathable and easy to wash. The shift was worn to sleep as a nightdress and stayed on during the day.

A pocket, similar to an apron, was tied around the waist over the shift. The pocket was fairly large, hanging down to the mid-calf or lower, and could be used to hold a range of items. Working class women would wear a linen apron, and those who could afford it had an apron made of lace.

A short gown was worn over the petticoat and was usually a contrasting color.. These had very long sleeves, buttoned or fastened in the front, and extended down to the mid-thigh. A large handkerchief, folded into a triangle, wrapped around the neck and was worn as a shawl.

The status of a woman could be revealed through many things, including her shoes and hat. Working women wore leather tie-up shoes, whereas wealthier women wore cloth-covered shoes. Working women wore straw hats instead of the more costly fabric hats with embroidery worn by higher-income women.

Formal Clothing for Women:

Formal gowns were worn by colonial women to special occasions, such as a ball. Gowns were much more elaborately designed and crafted than casual attire. They were typically made of silk, featuring crisp ruffles and frills along the bottom of the gown and around the elbows.

A bodice was layered over a corset for formal gowns. The corsets, known as a stay, were constructed of boning. The skirt was made of several yards of fabric which were draped and layered. The skirt was often cut to expose the bottom of the lighter skirt, called a petticoat, underneath.

Clothing Worn by Slaves:

Slaves made up a good portion of the Colonial population, and it is interesting to note the differences in their daily attire. Their arduous labor mostly consisted of working in the field and performing household tasks.

The main priority with slave clothing was for it be functional and practical for work. The garments were made from inexpensive fabrics that were imported specifically for outfitting slaves.Men wore a linen shirt paired with woolen hose and a knitted cap. Women wore things such as calico cloaks and aprons.

Plantation owners expected slaves to dress alike while working all day. To express their individuality, slaves would personalize their clothing by sewing decorative patches of fabric to their garments. Women would wear their hair in elaborate styles and wrap handkerchiefs around their head as head wraps.

Colonial plantation owners expected all slaves, whose days consisted of working in the field and performing household tasks, to dress alike. A male slave’s clothing consisted of a linen shirt, woolen hose and a knitted cap. These garments were constructed from inexpensive imported fabrics purchased specifically for outfitting slaves.

Women’s attire would include calico cloaks and aprons. Both male and female slaves attempted to personalize their clothing by wearing their hair in elaborate styles, using kerchiefs for head wraps and sewing decorative fabric patches to their garments.

Military Attire:

Other colonial soldiers did not wear the red coats, instead wearing fairly common everyday garments. They wore a felt-cocked hat, a black leather (or horsehair) neckstock and gaiters with matching knee straps. The gaiters served a similar function to spatterdashes and were worn over the outer pants leg and shoes.

Children’s Clothing:

Clothing for children were very restrictive earlier in the colonial period. Girls wore gowns, hoops, aprons, and a stomacher, just like adult women. Young boys were also required to wear stays because parents believed it would promote better posture. Even babies were tightly swaddled.

Eventually, around the mid-1700s, children were able to dress more freely. Frocks became the common garments worn by both boys and girls. These little dresses with sashes were worn by young boys until the transitioned into pants between the ages of 3 and 7.

16 Comments

Pingback:

“Uncover the Secrets: 14 Surprising Truths About Life in Early American Settlements That Will Change Your Perspective!” | IconoclasmicLinda Dudley

A distinction needs to be made concerning the phrase “During the Colonial times…” Most people in the general public tend to think of that to mean “all of the 1700s” and lump all of the details into one pot. The general thought is that things were the same from beginning to end – this couldn’t be further from the truth. Fashion, architecture, culture, politics, foodways, and more changed a great deal over the course of the century. Just imagine the first half of the 20thC and how much life changed!

Sticking to fashion, styles followed what was popular in Fance and England and were not more than 6 months behind (even on the frontiers). When reference is given to Colonial Williamsburg, that covers the late 1600s-1750s. Popular fashion trends included hoops (actually panniers) but not like the styles used in the Civil War. The panniers as shown on the Colonial Williamsburg site (referenced above) fazed out of common use by the 1760s and were reserved for fancy ball wear. For day wear, they were replaced through the period with, successively, hip, bum, and kidney rolls – pads in various sizes that added dimension to the appropriate part of the body.

Up to approximately 1772, common casual (undress attire) at home or day work attire included bedgowns (loose-fitting garment, not loose fabric) over a shift/chemise, stays (not “a stay”), pocket(s) and a petticote (or two or three depending on the temps). Note: petticote is like our modern skirt but a skirt is like a peplum on a jacket. Public (dressed) attire in towns would still be a gown, petticote, and handkerchief over shift, stays, and pocket(s). By 1778, in general the bedgown had been shortened and transformed into the shortgown. This is evidenced by estate inventories of the period (Cloth and Costume 1750 to 1800 by Tandy and Charles Hersh).

Need to run – more later. 🙂

Lester Angrisano

Have you ever considered publishing an ebook or guest authoring on other blogs? I have a blog based upon on the same ideas you discuss and would really like to have you share some stories/information. I know my audience would enjoy your work. If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to send me an e mail.

Lorraine Palamar

Take a look at “How to bustle a wedding dress” on Youtube. The instructions are quite good and show several ways to do the bustle.

Wendell Cochran

Regarding length of pockets: I checked my stash of grafted period patterns (books and photo copies)to affirm my disagreement on your asertion as to the length of pocket for the 18th century period. Pockets were worn for such a long time in fashion history, so I’m sure that length varied according to the shape of garments, the necessities of what to carry in one’s pocket, and the socio-economic situation of the wearers. Accoring to my research materials, pockets of examples from the 18th century varied in length from 14 inches to 18 inches (11 1/2″ wide), finished. The latter length and width seemed to be the norm. Also, about the article’s observation about the commonality of the use of cotton, one must be aware that prior to the invention of the cotton gin, cottom fabrics were enormosly more expensive to produce than either linen or wool. And, even silk. Most coton fabrics during the early to mid-1700s came from India where hand labor costs were dirt cheap. It was so cheap to export that it competed with domestic production of fabrics in Europe. France and England passed imbargo laws against the import of cotton for domestic consumption within each of the nations. It could be imported only as raw materials to be printed or dyed and then re-exported to other nations or locations, to the colonies in the Americas specifically. The additional manufacturing processes and the import and export taxes added greatly to the final prices of all cotton materials and goods. Linen remained the most common fabric in use in the colonies and the new Republic until the second quarter of the 1800s at which time slave labor was exploited in the Southern plantation culture. Through out the 1700s, linen could be made in every quality of goods from rough canvas to the finest gossimer-like qualities, and it could be dye almost every color and hue imaginable, in the yarn or in the woven goods. Many producers perfected the art of printing linen goods to mimic the motifs and appearances of India made “calico”. The disadvantage of Linen was the length of time and amount of effort it took to render the harvested stalks into supple strands of fibers ready to be spun into thread and eventually loom woven into fabric. After the introduction of the cotton gin, which could mechanically process raw cotton into useable fibers for weaving, American grown cotton quickly usurped linen’s place as the fabric of preference in the garment industry and decorative arts businesses. For all its exellant qualitys for durability, comfort, and practicality, the industrial revolution killed Linen as a viable fabric for the masses of consumers.

Wendell Cochran

How to fasten a wedding dress, or any other kind of 18th century gown: Buttons and button holes were not used during the 1700s. The common form of closing garments were A.) straight pins (later an improved pin called a blanket pin, similar to a flat unadorned metal broach), and, B.) a cord laced zig-zag fachion through hand sewn eyelets — some what like a shoe lace, except the cord was laced from top to bottom and not doubled back and criss-corssed like a modern shoe lace. Straight pins were sold in paper. There was a huge cottage industry in the slums of England where poor families, children, et al, would make straight pins at home by the thousands each year. Millions were exported to the colonies before the Industrial Revolution, where upon safety pins were manufactured cheaply and in great quantities by machine. Buttons were rarely used for day to day fasteners because it was time consuming and expensive to make buttons in great quantities by hand, therefore, buttons were reserved for decorations (false button holes and decorative jewel-like buttons), for prestigue (wealthy clients could afford unique-looking buttons) and to signify rank (military buttons were designed to indicate rank, regiment, and company). Hooks and eyes were also used for attaching garment pieces to other garment pieces, such as a dress top to a skirt at the waist band, and for closing some garments at the neck for cloaks and heavy coats. If you chose to close the garment down the center back with hooks and eyes, you will need to make/add a separate false overlay of the fashion fabric to conceal the possible gap-osis between the sets of hooks and bars/or/eyes. To keep the opening flat and stable, it was customary for dressmakers to insert ridged boning in the facing on each side of the center back opening (in a channel sewn at the edge of the facing turn back.) Quick reminder that the dress must (should/ought to) be made and fitted over a period “stay” or corset so that it the final garment bodice is form fitting to the shape and size of the wearer. There was almost no fitting ease; freedom of movement in the upper torso was provided by high, tight armscyes and curved sleeves. Never the less, movement was restriced; but for the wealthy with servants to do the drudge work, a lot of ease for movement to work wasn’t a prerequiste anyway. FYI: For more info on 19th century fasion, Dover Publications (catalog online) has some excellant, well documented instuction books on fashion and how-to-make books (with diagramed patterns) for beginners. I also suggest the book “Fiting and Proper” published by Scurlock Publishing Co., Texarkana, Texas; I got my used copy from

Aliberis.com, an online book sellers.

Diane

Here is a great bustle. Comfortable to wear and simple to make. http://www.trulyvictorian.net/tvxcart/product.php?productid=20&cat=3&page=1

Heather Jeanes

We benefit is so many ways in history and it often repeats its self.

blake gambini

that’s what I’m saying

goldberry

Interesting write-up. I’ve been reading a lot about Colonial clothing lately, and a few things don’t seem to match up. For one thing, stays were the predecessors of bras, and were worn by almost everyone almost all the time. I’m not sure why teh statement that they were “sometimes” worn. Also, I have never heard pockets described as so huge before. All the examples I’ve seen are less than a foot long. They were reacehd through a slit in the gown and petticoats, so it would be tough to reach them (and to walk) if they were hanging down around the calf.

I’m not a member of the reenacting community, but I know that reenactors are trying to correct some mistakes of the past, like the lack of stays. So just a word to the wise! 🙂

Jacquelyn

Thank you for your wonderfull articles,

I enjoy reading them very much.

Vija Lagzdins

Did the women’s dresses have a bussle in those days? What does a modern day bussle look like, for example, at the back of a wedding gown? How do you put one on?

I am a seamstress and a customer requested it on a wedding gown. I’m not sure what it should look like.

Thanks in advance for your response.

Expert Alterations By VIJA

Baltimore, MD

ELAINE B. FAVRE

What a delightful surprise! As a sewing buff, history major, former teacher, and former docent in a colonial Louisiana house museum, I found this interesting and informative. I look forward to reading the other offerings listed below this one. Thank you and please continue this feature.

Patti

I learned something new. Spatts were called spatterdashes. I have a picture of my great grandpop in spats that were about ankle high. Can you believe it, my mother, who was one of eight children wore high buttoned shoes as a toddler, handed down from her older sister. I have a picture of her on a tricycle taken around 1925. Very fun and interesting piece.

Canada W. Squizzero

The young man in the first picture at Plimoth Plantation is my son Justin. He really is getting his 20 minutes of fame!!!

blake gambini

word!