Textiles and Resistance: The Art of the Chilean Arpilleristas

Chile en venta [Chile on sale], Fondo Isabel Morel, colección Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, Aware Women Artists

Under Pinochet’s authoritarian regime, which began in 1973, human rights were suppressed through institutional fear, curfews, surveillance and acts of unspeakable violence. Hundreds of thousands of supposed “ideological enemies” were identified by the government and harshly punished or executed, sometimes just disappearing entirely with no trace. Meanwhile, women were forced into traditional, subservient roles, thereby removing their voices from political discourse and pushing them into silence. They suffered further still through the loss of family members, breadwinners, income, and even water and electricity, making life unbearably hard.

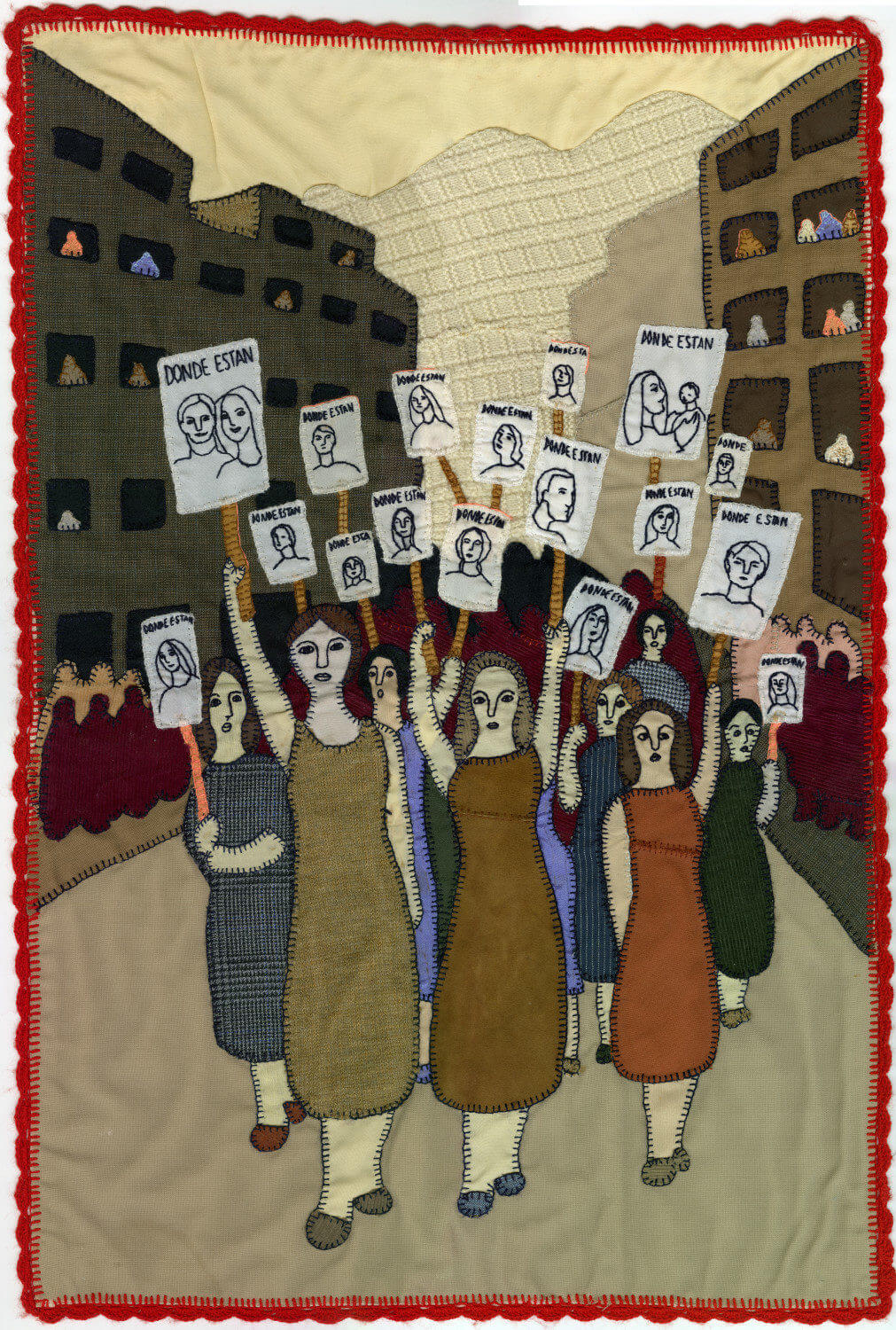

Marcha de mujeres de familiares de detenidos desaparecidos [March of women of relatives of disappeared detainees], Fondo Isabel Morel, colección Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, Aware Women Artists

Over time their imagery became increasingly politicised, documenting the harshest experiences of poverty, hunger, violence and destruction they were forced to live through. Many also included within their imagery a blazing sun, as a symbol of resistance, and hope for a brighter future, even during the darkest of times. They thereby began using textiles as a potent means of self-expression at a time when their voices had been removed from the wider political sphere.

When international networks began smuggling the textiles out of Chile, their sales provided a much-needed income for these struggling women. But they also acted as newspaper stories at a time when so much of the Chilean regime had been muted, exposing to the wider world the gritty, brutal realities of life during this time. The migration of these textiles also served a further purpose, leading to the formation of a wider network of women, who gathered in solidarity and support for the Arpilleristas.

Pinochet’s government branded arpilleras as “tapestries of defamation”, confiscating and destroying any textiles they came across, while makers remained anonymous, only signing their work with their initials to protect them from incarceration. Yet a large majority of these textiles escaped censorship, thus becoming a vital means of political and cultural expression for marginalised, feminine voices.

Today, arpilleras are still made in Chile, documenting themes that would have been branded as subversive by Pinochet’s brutalist regime, such as feminism, environmental concerns, and communal activities. Meanwhile, their role in bringing out women’s voices through the seemingly innocuous form of patchwork has gone on to inspire countless other artists since, including Carolina Caycedo’s politically engaged installation art, which often incorporates woven and embroidered clothing, and Maria Guzman Capron, whose multilayered soft sculptures, made from fabric, explore issues around identity politics and power dynamics.

Leave a comment