A Leap into the Unknown: Diaghilev and Matisse

Henri Matisse and Léonide Massine preparing the ballet Le Chant du Rossignol with the mechanical Nightingale

Of all the adventurous art projects Henri Matisse took on throughout his lifetime, his collaboration with Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes would prove one of the most challenging, pushing him in ways he never could have imagined. Working with Diaghilev on the 1920 production of Le Chant du Rossignol (The Song of the Nightingale) Matisse took daring, risky leaps into the unknown, exploring how his two-dimensional colours and patterns could come bursting into life on the stage. Reflecting back on the experience Matisse wrote, “I learned what a stage set could be. I learned that you could think of it as a picture with colours that move.”

Diaghilev approached Matisse in 1919, asking him to collaborate on the 1920 production of Le Chant du Rossignol for the Paris Opera, written by Igor Stravinsky with choreography by Leonide Massine. Matisse was initially hesitant, sensing the enormity of the task, but Diaghilev had a way of persuading people, perhaps through a mix of flattery, charm, and finance. The Chinese court setting for the story might have piqued Matisse’s interest too, given his enduring fascination with Orientalism. Matisse eventually agreed, declaring with some conviction, “But I’ll only do one ballet and it’ll be an experiment for me.”

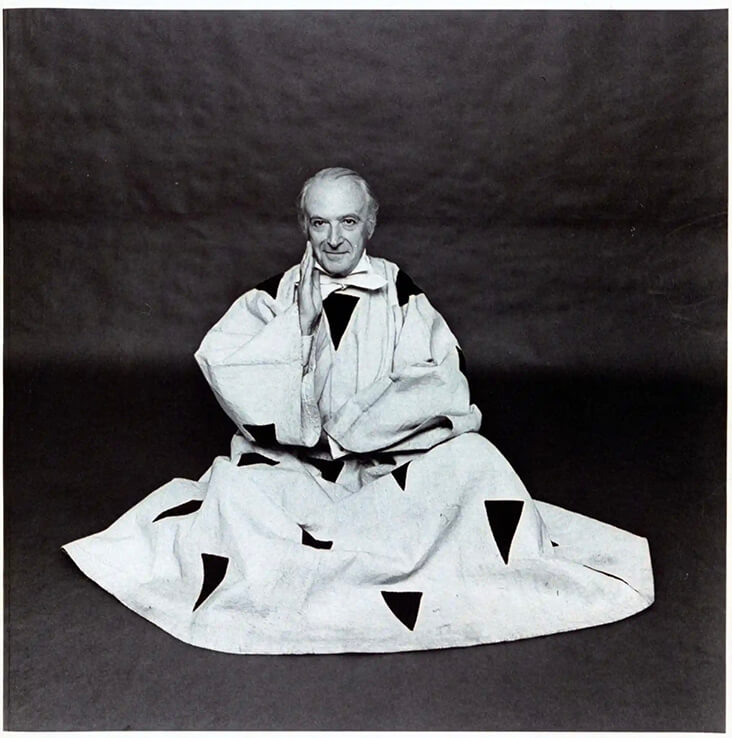

Cecil Beaton wearing a felt and velvet costume designed by Henri Matisse for Le Chant du Rossignol, 1920

Matisse initially planned to execute the designs for sets and costumes in his home at Issy-les-Moulineaux just outside Paris, and send them to the Empire Theatre in London, where the Ballets Russes was carrying out its rehearsals. But he soon changed his mind, deciding he should like to work alongside the theatre company as the entire project unfolded. Being in London also gave Matisse access to the Victoria and Albert Museum, which would profoundly influence his Oriental costume designs for the Chinese Emperor and his courtiers.

Matisse not only designed costumes, sets, curtains and stage props, but also became closely involved in the production of his ideas, hand painting his patterns directly onto costumes and curtains alongside a dedicated team and working closely with the development of angular jewellery to be seen from afar. In order to help visualise his overall stage design, Matisse turned a wooden crate into a diorama, which he filled with cut pieces of coloured paper, the first example of the cut-paper work that he would return to in his later years.

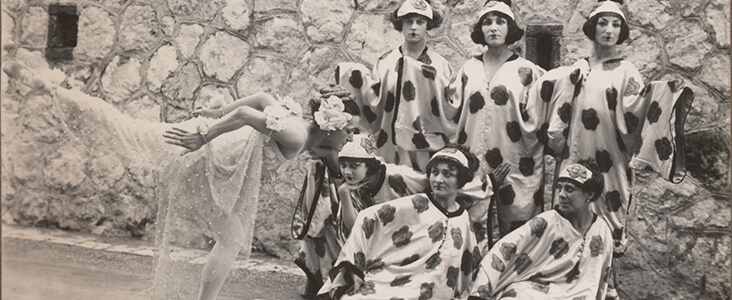

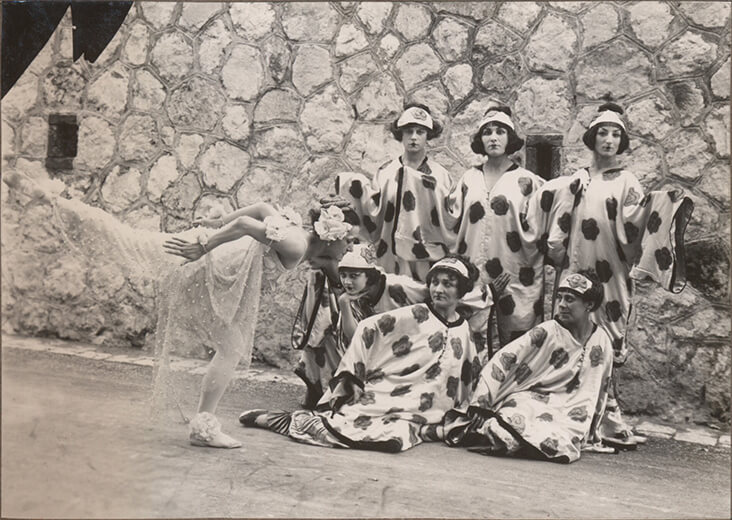

This process allowed Matisse to envision a turquoise blue backdrop and black ground which formed a sharp contrast with the array of rainbow-coloured costumes in red, pink, yellow and green, featuring abstract geometric or floral motifs in repeat patterns. These figures formed a flurry of frenetic coloured energy, circulating around the dead Emperor in the centre, who remained static throughout the entire ballet, drenched in black on a bed throne. At the climax of the story, when the Emperor is brought back to life by the nightingale’s song, a dazzling red train painted with a golden dragon unfurled to fill the entire stage.

Although Matisse had this colour scheme planned out in advance on a small scale, when it came to enlarging his ideas to life-size, he encountered a series of unforeseen issues. Theatrical lighting changed the way his black ground looked, making it appear red in tone and forcing him to shift instead to a Prussian blue. Matisse was also quite taken aback at how movement changed the nature of his costume designs, disguising or concealing areas of colour and pattern that he had considered vital to his overall design. Working closely with Matisse, the choreographer Massine changed his original sequences to suit the dancer’s costumes, a move which prompted critics to deride the performance for its ‘hermetic choreography.’

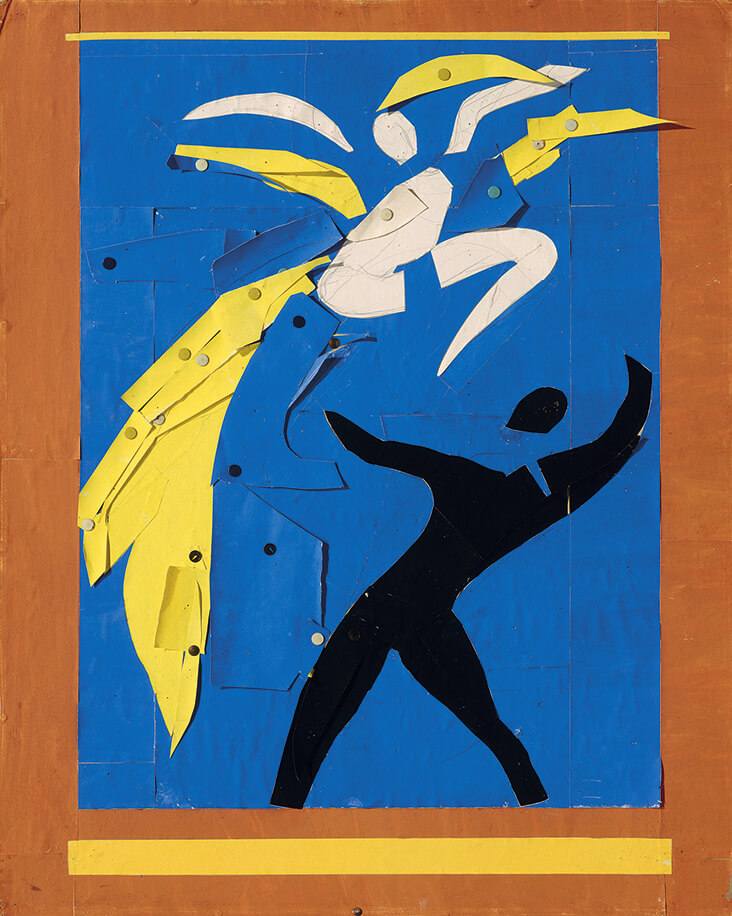

Despite the setbacks and criticism, Matisse would later return to the Ballets Russes in 1937, some years after Diaghilev’s death in 1929, creating sets and costumes for the ballet Rouge et Noir in Monte Carlo. This time Matisse had more confidence in his overall vision, linking set and costume together with the same limited colour schemes of red, yellow, blue and black, a vision one critic praised as “like an abstract painting set in motion.” Onto the dancer’s costumes he placed a random smattering of flame shapes which appeared to flicker and move with bodies through space.

Although Matisse loved dance throughout his entire career, his experiences with ballet undoubtedly shaped the nature of his art throughout the 1920s and beyond. The scope and scale of ambitious public art commissions such as the Barnes Mural in Pennsylvania and the Vence Chapel in Nice particularly nod towards the theatricality of ballet, exploring how simple, understated arrangements of colour, light and pattern on a vast, all-encompassing scale can completely transform the space around it.

2 Comments

Rene Azzara

Fabulous!! Thank you for writing this. I immensely enjoyed it.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you so much!