Lee Krasner: Inner Rhythm

“I never violate an inner rhythm. I know it is essential for me. I listen to it and I stay with it. I have regards for the inner voice.”

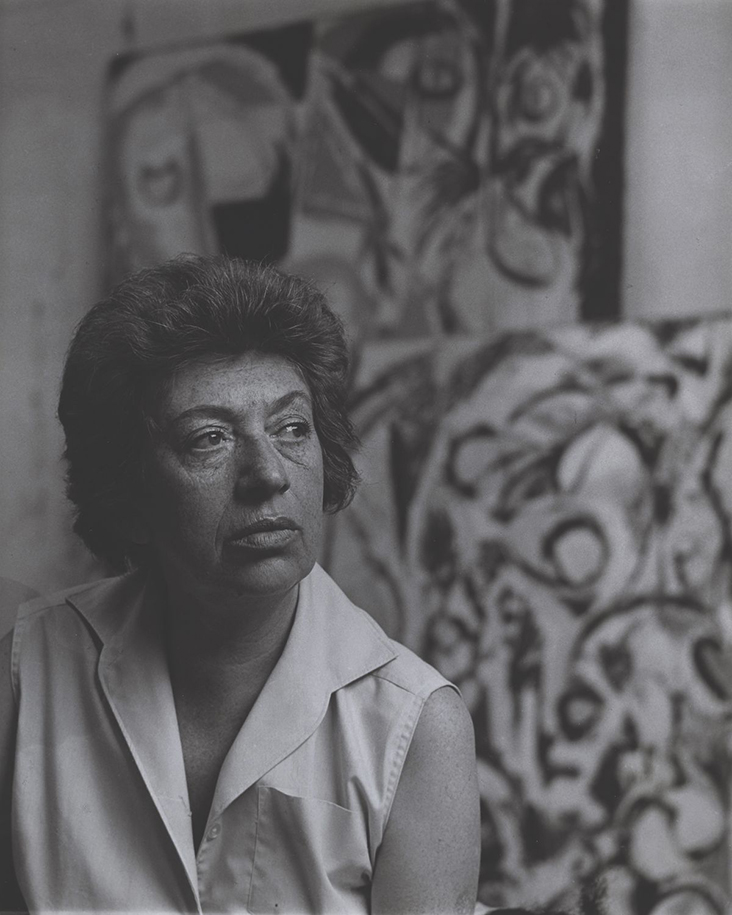

Tense, violent and shockingly bright, Lee Krasner’s abstract canvases vibrate with pulsating rhythm as if lost in their own inner tempo. Krasner was a force of nature, a pioneering Abstract Expressionist who painted fervently and prolifically for 50 years, yet she is more commonly known today as “Jackson Pollock’s wife.” Though her career was eclipsed by that of her world famous husband, she established a successful, influential career in her own right during her lifetime and her work is held in major museum collections around the world. London’s Barbican Gallery is currently presenting Living Colour, Europe’s first major showcase of her work for over 50 years; the show features over 100 paintings which bring to life the breadth and variety of her practice, as well as highlighting the vital role she played in the development of New York’s Abstract Expressionism. Curator Eleanor Nairne observes, “Hers is a story of great tenacity.”

Krasner was born Lena Krassner in Brooklyn in 1908, to a family of Russian-Jewish Yiddish speaking immigrants who had fled from their shletl outside Odessa, giving the artist a rich family history that would later feed into her art practice. Her parents owned a grocery store and fishmongers in the East side of New York but they often struggled to get by with seven children to raise. From early on Krasner was tenacious and strong willed – after choosing to pursue a path in the arts at the age of 13, she hunted down the only school in New York that offered advanced art courses for girls, gaining entry after her second attempt to the Washington Irving all-girls High School in Manhattan, a 2 hour daily round trip from her home in Brooklyn. In one of her first acts of reinvention she changed her name to “Lenore,” after Edgar Allen Poe’s famous poem. Her parents didn’t push her ambition, as she remembers, “(they) didn’t encourage me, but as long as I didn’t present them with any problems, neither did they interfere.”

After leaving school Krasner moved on to the Cooper Union in New York to study fine art, where she changed her name again, this time to the more androgynous “Lee”, and soon after dropped the second ‘s’ from her name. Moving on to the Art Students League, and later the traditional National Academy of Design, she was often criticised by teachers for her wilful independence, or for veering into artistic territory deemed more suited to men. Undeterred, Krasner continued to push herself, maintaining a steady flow of work even through the great depression of 1929 in the form of murals and mosaic designs found through the public art scheme known as the Works Projects Administration (WPA).

Krasner lived with her fellow Russian painter Igor Pantuhoff in New York for the next ten years, although his family’s anti-Semitic views would eventually come between them. In the later 1930s, Krasner integrated herself with New York’s bohemian art circles where she found a group of ostly male, likeminded spirits including Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Taking on art classes at Hans Hoffman’s radical 9th Street School was a game-changer, opening her eyes to a new way of seeing, thinking and working. Hoffman’s alternative teaching methods encouraged processes of destruction and reinvention which Krasner would soon integrate into her own work, greatly impressing her tutor, though in a backhanded compliment he callously described her work as “so good you would not know it was done by a woman.” Krasner met the older abstractionist Piet Mondrian during this time, who offered more generous praise, celebrating her “very strong inner rhythm.”

Hoffman also introduced Krasner to the fragmented language of Cubism and Matisse’s cut and paste aesthetic, influences that can be seen in her early charcoal drawings of disjointed, abstracted human bodies drawn with sweeping, energetic strokes that move dynamically across the picture plane. Though she was wrestling with new ideas, in a phase she called her “grey slab paintings,” the “all-over” rhythmic language explored here would become one of Krasner’s defining features, expanding in unprecedented ways in the following decades. As a founding member of New York’s American Abstract Artists group in the years that followed Lee’s voice was vital in promoting the public appreciation of abstraction, and it was through social events organised by this group that she first met and fell for Jackson Pollock. When Krasner first saw Pollock’s paintings, in a display including her own work, she was thunderstruck, remembering, “When I saw his paintings I almost died. They bowled me over. Then I met him and that was it.”

Krasner had found in Pollock and intellectual equal, so much so she was prepared to overlook his volatile character and excessive drinking habits, moving to live with him in New York in 1942. By 1945 they were married, and later that year, with some assistance from Pollock’s gallerist Peggy Guggenheim, the cash strapped young artists were able to buy a ramshackle, run down barn house in Springs, Long Island. With no heating or indoor bathroom they lived an ascetic life, driven by a shared desire to pursue their art. In their poverty they seemed content, gardening and taking long bike rides together, while both worked furiously and determinedly in their own separate studios, her working in an upstairs bedroom and him in the outside barn, only critiquing each other’s work “by invitation.” But Pollock was on the brink of international stardom, with Life Magazine asking of him in 1949, “Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” Some accounts suggest Krasner put her own career on hold to support her husband’s, but in fact Krasner never stopped working, and both were as aggressively ambitious and prolific as each other, though Krasner was well aware of the macho tendencies of the Abstract Expressionists and the boys club antics they encouraged within their group, as well as the culture for promoting heroism and bravado.

Krasner began her breakthrough Little Images series from 1946-50, with intensely worked, dense compositions made from patches of fractured colour and white, linear designs. Intuitive, and often destructive processes of discovery were vital to her working method, as she wrote, “I like a canvas to breathe and be alive. Be alive is the point. And, as the limitations are something called pigment and canvas, let’s see if I can do it.” In these small canvases she also made reference to Jewish Mysticism, or Kabalah, allowing her family heritage to come through in oblique ways, with shapes moving from right to left, or the inclusion of Kabalistic symbols. Though increasingly abstract, she asserted the cultural and autobiographical significance of her practice, writing, “My painting is so autobiographical, if anyone can take the trouble to read it.”

Krasner and Pollock’s marriage had hit the rocks by the mid-1950s as Pollock’s womanizing and alcoholism spiralled out of control. The destructive turmoil of Krasner’s personal life came to play out in her art as she recklessly tore up paintings with fits of rage, later reassembling them in new ways. When she exhibited these new, deconstructed works in 1955 they received rave reviews, particularly from New York’s champion of abstraction, Clement Greenberg. Though Pollock’s reckless behaviour threatened to tear them apart, Krasner was still devoted to him, often taking on the role as his carer. When asked why they never had children, Krasner referred to Pollock as the child in their relationship, before adding, “I married him to become an artist, not a mother.” When Pollock’s fame threatened to engulf him he stopped painting, while Krasner continued on.

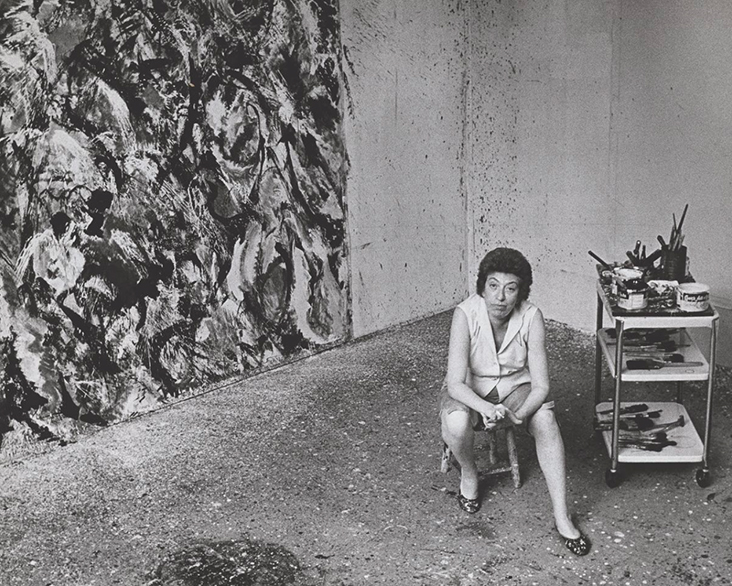

Just a year later, while Krasner was away travelling in Europe, Pollock died in a car crash while drunk-driving – his mistress, Ruth Kligman had also been in the car but survived. Krasner was blinded by grief, while even years later friends suggested she never truly recovered from the shock. Krasner chose to remain in their home at Long Island and painting became an outlet for her grief – as if in homage to her husband, she took up residence in his barn studio and blasted through her grief with an outpouring of creativity, producing vastly proportioned paintings in a phase now seen as the most successful and productive period of her life. Helen Harrison, director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Centre observes, “It is mind boggling. Straight away she does this wonderful, colourful, upbeat work. Painting was her antidote to grief.” Wild, chaotic and expressive, the work from this period onwards was often made at night, including her “Umber Paintings” which she also called “Night Journeys”, made during bouts of grief induced insomnia which worsened worse after her mother’s death in 1959. Following these works Krasner moved towards a brighter palette, broadening her language even further still.

Krasner has often been described as a style chameleon who cycled between different styles and methods, but there is an innate sense of movement, rhythm and psychological intensity that ties all her work together. There is a sense, in these later works, that she is processing deeply held emotions through her art. Nairn observes, “The fixed image terrified her. She felt that it was an inauthentic gesture to think that some singular imagery could contain everything that she was as a person. She went through these cycles of work and these rhythms, and it was often a very painful process.”

Towards the end of her career Krasner’s work seemed to finally be receiving its due, with a major retrospective at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts in Texas which travelled widely throughout the United States, culminating at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In the last paintings she made before her death in 1984, Krasner seemed to bring together many of the styles she had cycled through in a 50 year long career, including elements of drawing, collage and painting, as if finally finding some points of resolution.

In the years following her death Krasner’s work has steadily grown in popularity, while her legacy has continued with the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, set up with donations after her death to support the next generation of leading artists. Her work is reaching progressively higher prices at auction today, which are set to rise even higher given the success of her Barbican retrospective. As one of few women associated with the macho world of Abstract Expressionism Krasner proved women could charge through territory dominated by men and find their own path – today’s expressive, bravado women painters, including Cecily Brown, Jenny Saville and Marlene Dumas have clearly taken note. Reflecting on the obstacles she charged through like dynamite, she wrote, “I was a woman, Jewish, a widow, a damn good painter, thank you, and a little too independent.”

Feature Image: Lee Krasner, The Seasons, 1957

2 Comments

Taryn Yamane

This is one of my favorite movements in art and I love hearing about female artists who persisted in creating phenomenal works, despite of the lack of recognition that the men received in the male-dominated field of Abstract Expressionism. True artists. Thank you for shedding light on Lee Krasner’s boldly expressive creativity Rosie!

Vicki Lang

Love the boldness and whole surface use of Krasner’s work. Some thing to pick out in different areas.