Why We Need Craft – From Waterways To Social Media

As consumers we engage with a hybrid of art, design and craft, and its artefacts to form social bonds, and a sense of identity: I am a Nordstrom person, a Harrods; Bloomingdale’s or John Lewis… It is an engagement which helps comprehend and navigate our daily lives. Ceramics or textiles, for instance, can give us a visceral connection to the world we live in. Craft, seen in this context, can be a stabilising force in unsettled times. The globalised world is too large to comprehend within nuanced identities but relies upon broad brushstrokes: a revolving catwalk of quickly sketched caricatures of peoples, cultures and their perceived styles and values. Globalism and populism are influencing our day-to-day experiences, and design needs to respond to these influences – but how?

Large load of combed hemp is pulled into courtyard for weaving by two small horses in Italy. Photographed by George Silk for LIFE Magazine / 1944-05

Well, the London Design Biennale recently brought together 40 countries, cities and territories. The Artistic Director of the biennale comments: ‘ [it] investigates the important relationship between design, strong emotional responses, and real social needs’ where designers can ‘create new social possibilities and more positive conditions for human flourishing.’ And Fashion too, has returned to the importance of craft and emotions: from Dior’s knitted dresses to Jill Sander’s recent use of crochet in their collection; craft is at the forefront: “We want emotion,” comments Jill Sander’s creative director Lucie Meier. “It’s industrialization that kills everything’.

It is this connection with ‘emotion’ which is central to how we understand design today – it goes beyond simple function and materials. Through the alchemy of the designer an immersive – even spiritual – connection with the user can be established. A connection that underpins contemporary design. A sense of ‘place’ is important too. Design often oscillates between the local and global: between its manufacture and inspiration; to how and where it is used and consumed. Fashion is an example of this unique position in design.

Fashion of course is a global industry par excellence; although a long-time plunderer of visual cultures it can also locate the places of skills and craft within ‘fashion districts’ in cities and provinces. But as consumers we are inclined to focus on the point of purchase rather than the place of manufacture: John Lewis, Macey’s, Target, and increasingly Amazon and Alibaba; over Stoke on Trent, Detroit, or Hainan Island China, and their incumbent links to creative or industrial output. Any Sense-of-Place is can be obscured by the entry stamp to a globalised world. A world increasingly populated by handheld mobile devices which allow us to facetime our friends locally whilst engaging in twitter trends globally. The invisible flows of information which ebb on our screens compound the sense of a virtual – placeless – world: we no longer need to walk to the 24/7 convenience store because we are now plugged-into a 24/7 information store – Google!

Designers, and makers, can play a role in re-connecting us to a sense of place: both the locality of making, and by making visible the ‘road-travelled’ for the raw materials used. Hobbyists and makers alike can, in many cases quite literally, weave a history into their products by re- establishing a history to the place of its making: the social practices in construction or use. Weaving and embroidery, for example, share a long history of women working collectively and has been used to give voice, or empower, the domestic sphere of much early craft-making. This history has new resonance to a #metoo generation. Craft orientated online platforms from Etsy to social enterprise like Love Craft and DMC. The latter provides a support framework: including workshops, inspiration blogs and materials needed for the ‘handmade’. DMC also capture one other strand of craft when it states ‘[The] Handmade is about living more mindfully’.

Indian activist Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) works on a weaving machine, circa 1930. Photo by Pictorial Parade/Getty Images

Google is often the gateway to the so-called ‘Network Society”. A society which is often understood through a series of watery metaphors – from Amazon, to surfing the net, and the flows of currency – allowing us to comprehend the invisible network, metaphorically at least, to which we are plugged-in to. Metaphors are useful in allowing us to see something new, and outside of our experience, by referencing something we know and understand. A metaphor provides a safe place to understand complicated, and environmentally worrying, changes to life today. Perversely I have been inspired by these metaphors to provide a jumping-back point. A point from which to look at the history of craft design and making. Looking at social networks, and their histories, created by design and craft over the last 100 years or so.

The purpose of these essays is to disentangle histories in art and craft. How place and the environment are imbedded in craft today. Craft can provide psychological and physical traction beyond pure consumer choice. By tracing the UK waterways from the Chelsea Docks, in London to Nottingham and its lacemaking tradition; from ceramics in Stoke-on-Trent to the textiles and crafts alongside the rivers and canals of Northern England. These early physical networks of commerce and industry will navigate us towards the data-driven ‘networks’ of today.

This journey will look at relationships between local culture and creativity. In a google mapped world where everything is flattened into pixels dictated by screen size. It is easy to miss the nuances and specificities of place. Even the symbolism of unfolding a physical map – to remind us of the three-dimensional, temporal quality of space – is lost.

Over the coming posts we will lay out a landscape of crafts. Iron out the wrinkles and, maybe, weave in a few contours and creases of our own!

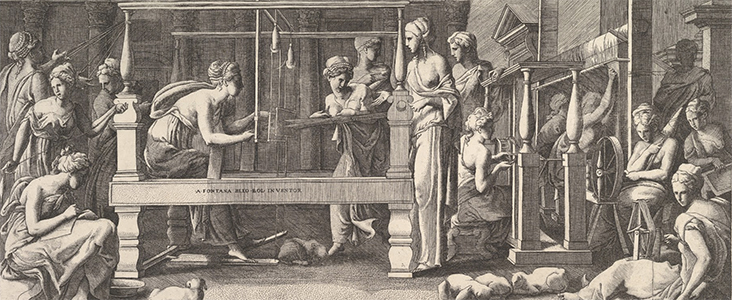

Feature Image: Women spinning, weaving and sewing / Francesco Primaticcio / 1540–50

One Comment

Vicki Lang

Thank you for such a knowledgeable article. I am a needle worker-quilting, embroidery, sewing. Seeing other artists’ work is very inspiring.