Finery and Lace: Embroidery in Europe

From Viking Age clothing to Catholic vestments and prestigious royal gowns, European embroidery has a rich history that is closely intertwined with our cultural past. Europe was also a site for embroidery innovation; techniques that were discovered here continue to live on today in the clothes we wear and the ways we decorate our homes. What this proves is how deeply connected we still are to the people of Europe’s past, through this timeless and enduring art form.

The history of European embroidery is often traced back to the Viking Age of the 9th and 10th centuries. Many fragments of ancient embroidery have been discovered in ancient burial sites across Sweden, Denmark and Norway, proving the important role of decorative textiles in Viking societies. One of the most celebrated of these burial sites is the famous Bjerringhøj mound in Denmark. Archaeologists made this fascinating discovery in the late 19th century – such was the intricacy of the surviving textiles fragments, featuring silk, gold and silver threads, many believe they once belonged to royalty.

Embroidery was a widespread practice across all aspects of society by the Middle Ages, from the homes of ordinary people to the master workshops of professional craftsmen. Anglo-Saxon England was particularly renowned for its highly skilled embroiderers, who developed an innovative and influential style featuring knotwork, floral and animal motifs, and roundals, a style that permeated across much of Europe. They created prized garments and wall hangings featuring shimmering gold and silver threads for only the wealthiest and most prestigious members of society – namely, royalty and the Catholic church.

From this period onwards Europe became a site for embroidery innovation, dazzling the world with stunning gilded Catholic vestments, textiles and royal gowns drenched in silver thread. One of the most famous examples is the stunning Bayeux Tapestry, dating from the 11th century. It is thought it was first commissioned to decorate the cathedral of Bayeux, illustrating the conquest of England by William, Duke of Normandy in 1066. At over 70 metres long, it is one of the largest embroideries ever made. We don’t know who made the embroidered tapestry, but it demonstrates the typical Anglo-Saxon style, with decorative detailing, stem and outline stitchwork, and laid and couched work.

Dating from the slightly later 16th century Tudor period, Queen Elizabeth I’s famous Bacton Altar Cloth is one of only a few royal garments surviving from this period, and its exquisitely fine detail, featuring curling flowers, birds and animals, is testament to the skill of the embroiderers who made it, particularly as it still survives 500 years later.

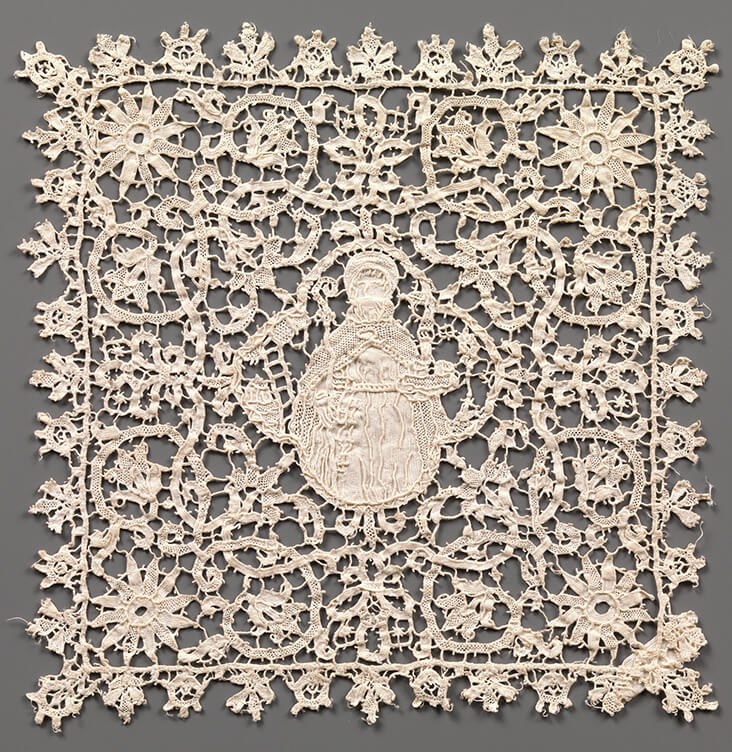

Another of Europe’s most important contributions to the history of embroidery was lace. Emerging in the 16th century, early styles of lace first appeared in Italy, Flanders and France, before becoming more widespread across much of Europe. Lace was a marker of luxury and status because it was such a time-consuming fabric to create, and it involved the handiwork of highly skilled makers. It was made with a single needle and thread, or with threads plaited together into strands. Handmade lace adorned the clothing and interiors of royalty and aristocratic men and women for the next two centuries, decorating cuffs, collars, shoulders, hands, heads and home furnishings.

The industrial revolution of the 19th century had a monumental impact on the nature of European embroidery, as machines gradually emerged that could recreate what was once only possible by hand for a fraction of the cost. If this meant taste for expensive, hand-made embroidery waned during this time, the Arts and Crafts movement in the 20th century did much to revive taste for the appeal of hand-made embroidery, particularly the Scottish artist Phoebe Anna Traquair, whose illustrative embroidered panels show how overwhelmingly powerful, visceral and tactile the art of embroidery can be.

Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen, 2017, a collection featuring fine lace knits and elements of narrative embroidery

In recent times, hand-made embroidery in Europe has seen a huge resurgence, particularly among makers artists and designers who want to embrace slow fashion made with care and attention, that is built to last, an antidote to the wasteful habits of fast-fashion retailers. Stitch School, established in London in 2017 by Aimee Betts and Melanie Bowles, aims to re-introduce the fine art of embroidery to a new generation of makers, while London’s Royal School of Needlework has seen a huge uptick of students signing up for embroidery courses. British designers such as Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen are re-introducing the incredible nature of hand-made embroidery back into the fashion landscape, proving how much spark and life there is within this masterful and highly skilled art form.

8 Comments

Pamela Armstrong

I love these posts, and want to contribute a book recommendation that is sure to appeal to all fabric lovers!

Virginia Postrel’s “The Fabric of Civilization – How Textiles Made the World is a fascinating read and resource (many footnotes and references) for furthering knowledge of fibers, weaving, embroidery and textiles around the world. I have always felt on some level that cloth is the center of the universe, and this book proves that intuition to be true!

Lauren Gates

Thanks for the recommendation Pamela, And if I may also chime in with a book recommendation along the same thread 😛 The Golden Thread: How Fabric Changed History by Kassia St Clair is also a fascinating read on the subject of textiles and their impact throughout history. I’m going to get myself a copy of your recommended book, thank you!

Vicki Lang

What beautiful stitchery from the past. I have a book originally from Therese de Dillmont. She opened an embroidery school around 1846 and published my book in 1884. Mine is the 3rd printing. I can’t wait to do some lace.

Lorraine Palamar

Hand made lace was very time-consuming. It could take a year to make one foot of lace so only the very rich could afford it. Some of the lace-makers would go blind from the work, it was so intricate.

Karen Bell

Yes the lace is beautiful but a cruel and blinding profession to adorn the very wealthy.

Without mentioning the actual humans and conditions to create these fabrics you leave a hole in the story. Nothing to honor the artist…all that is important is the finished product.

Karen Sheridan

The Royal School of Needlework teaches many of this techniques and students can actually earn certificates in these skills. Embroidery of all kinds is experiencing renewed interest and its not just for us little old ladies any longer. On youtube we are know as flosstube and there are hundreds of stitchers making videos. The RSN is also creating a library of stitches to preserve the art and people can sponsor the effort by contributing to the stitch of their choice. Sajou of Paris has beautiful things for stitchers and sells a tapestry pattern that I believe is a reproduction of a portion of an antique. Crosstitch, hardanger, goldwork, needlepainting …its goes on and on its a art will many techniques.

Sherry Berbit

I totally agree with Margaret’s comments, above. I look forward to your postings, they never disappoint. I’ve always loved embroidery, harkening back to the days I wore hip hugger bell bottoms which I embroidered with flowers and leaves up the sides of the legs- wonder what ever happened to those ….. I so loved them, thanks for another great mini lesson, Rosie.

Margaret Hough

I just want you to know how much I appreciate your historical articles. It is enjoyable to learn about art history, colours, fabrics, and historical additions and modifications. It makes coming to this site each day a lovely experience. thank you