The Magic of Mexico: Frida Kahlo’s Fabric

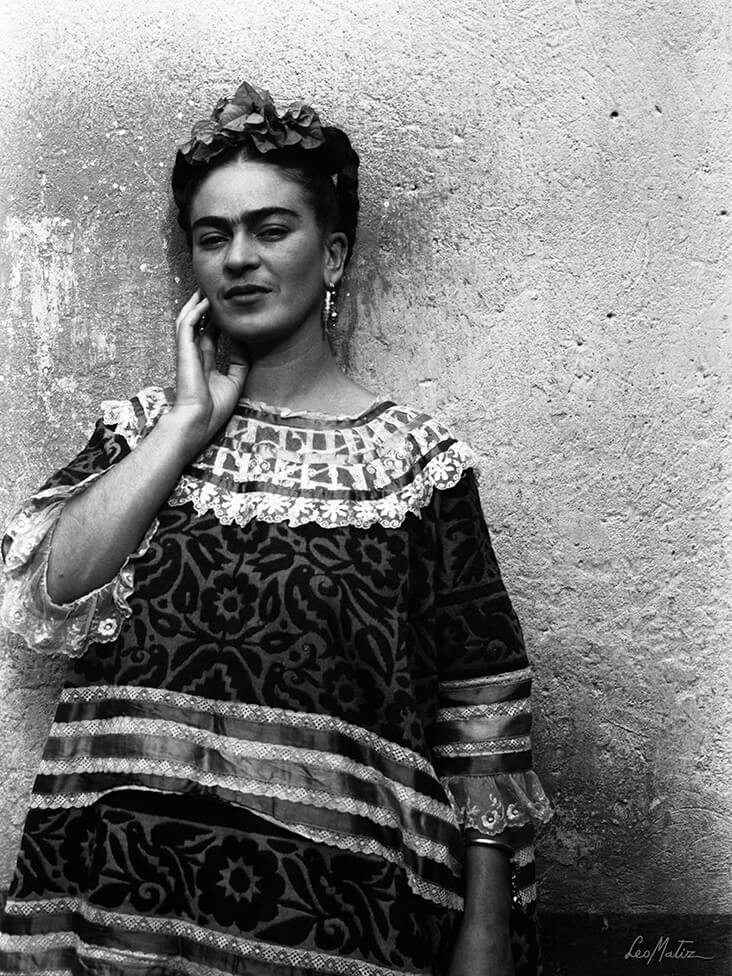

For Mexican artist Frida Kahlo fabric was an incredibly powerful form of self-expression, one that made her an inimitable icon of the 20th century. She adored the indigenous fabrics of Mexico, with their lively, exuberant prints and intricate areas of ruffling and embroidery, drenching her body in layers and layers of traditional textiles. More than just an aesthetic choice, these fabrics and garments became potent signifiers of Frida’s proud patriotism, expressing her ardent allegiance to Mexico. But they were also a great source of comfort and armour, concealing and protecting the physical ailments that so often feature in Kahlo’s art, and transforming them into a symbol of defiance and strength.

Frida Kahlo, by Leo Matiz, 1943, Coyoacán, Mexico. Private Collection. © Alejandra Matiz. Leo Matiz Foundation.

Kahlo was born in 1907 in a house known as Le Casa Azul (the Blue House) on the outskirts of Mexico, to a German father and Mexican mother. After contracting polio at the age of six, one of Kahlo’s legs grew smaller and thinner than the other, and from this young age, Kahlo adopted a pattern of wearing long, patterned skirts and layering three or four socks over one another to build a support inside her shoe. Fashion, she began to sense, could act as a form of transformation and disguise. The near-fatal bus accident Kahlo suffered as an adolescent in 1925 left her with lifelong spinal injuries that forced Kahlo to wear plaster and leather corsets to hold her body together, and this, too profoundly shaped Kahlo’s attitude towards clothing.

As Kahlo’s artistic practice expanded in the late 1920s, she began adopting the traditional Mexican Tehuana style of dressing, with ornate headpieces featuring pleats and ribbons, a huipil or short blouse and a long, patterned skirt. On the one hand, this dress style was part of Kahlo’s family history – photographic evidence shows Kahlo’s mother styled in Tehuana clothing. Kahlo may well have also chosen this style for its associations with the powerful, matriarchal society where the style originated, in the Tehuantepec Isthmus, in southeast Mexico, Oaxaca.

Kahlo’s adoption of the Tehuana style came during a politically charged time for Mexico, when José Vasconcelos, the Mexican Minister of Education, was encouraging the adoption of traditional Mexican values. Kahlo’s husband, Diego Rivera was a leading Mexican muralist and Kahlo’s celebration of Mexico chimed well with his political beliefs. Both artists rejected the homogenised Hollywood style for a socialist celebration of indigenous Mexico and its ability to connect with the pueblo, or people. Kahlo was 20 years younger than her husband Rivera and this Mexican fabric and clothing, with its brilliantly bold colours and prints, made her stand out from him wherever she went. When exhibiting her work in Paris, Kahlo’s clothing attracted as much attention as her art, while on the streets of San Francisco, children would ask her, “Hey, where’s the circus?”

Sometimes Kahlo would mix up the Tehuana dress with pieces from Chiapas and other Mexican regions, including rebozos (fringed shawls), enaguas (skirts) and holanes (flounces). She even included traditional European garments such as embroidered blouses, looking back to her father’s German history, or mixed things up with hand-painted corsets featuring religious and communist symbolism. But Kahlo almost always maintained the Tehuana style of construction with a short blouse and long skirt. Kahlo also cannily observed how the Tehuana emphasised the torso and head with intricate areas of adornment and jewellery, drawing attention away from the lower body and this was significant for Kahlo, allowing her to transcend the areas where her disabilities lay.

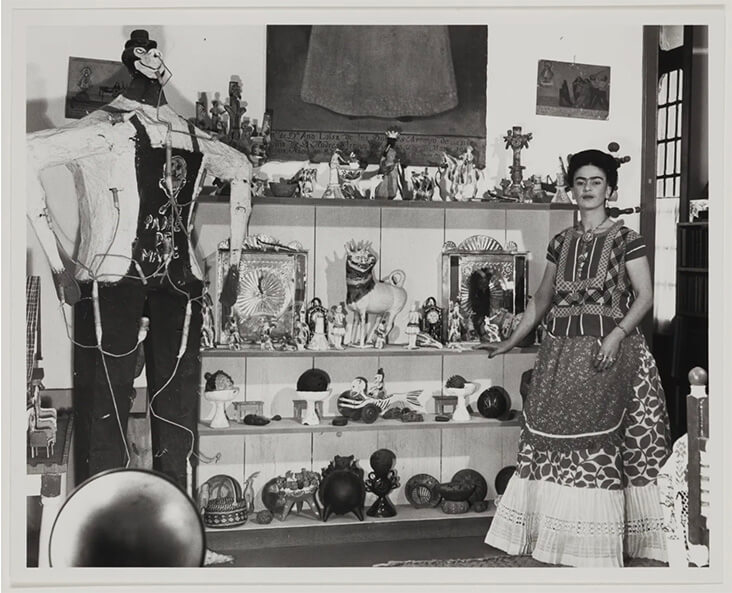

Beyond its political leanings and attention-grabbing potential, Mexican fabric and clothing were also a great source of comfort to Kahlo as she struggled to cope with increasingly challenging health issues. She found the soft silks and cottons of Tehuana clothing easier to wear because they were gentler and more comforting on her fragile frame, while short, loose huipil blouses skimmed gracefully over the restrictive corsets she had to wear underneath. As Kahlo’s health deteriorated she continued to use fabric and fashion as a means of self-expression and freedom, one that allowed her to escape from her pain and suffering. Mexican curator Circe Henestrosa observed how, “The more she was suffering or worse she was feeling, the more adornment she would wear.” This focus on the celebratory, uplifting nature of fabric extended into Kahlo’s home, which she filled with the exuberant and joyful prints, patterns and textures of Mexico. Hilda Trujillo, Director of La Casa Azul Museum sees this escapist attitude Kahlo had to clothing, fabric and art as her greatest legacy, pointing out, “It’s this interpretation that young people can relate to today, a woman that suffered many injuries but who was able to transform this pain into art.”

4 Comments

Jay Evert

Kahlo suffered even more. During the bus accident, a metal rod pierced her abdomen and ran through her uterus. This long-term damage also caused pain and suffering. She was left unable to carry a pregnancy to term, which caused great emotional pain.

Maureen Christensen

I have always been curious about Frieda Kahlo…Thank you for such an interesting article.

Marilee Henneberger

I saw an exhibit [was it last year or two ago?] of Kahlos’ clothing. At first glance, the outfits seemed discordant and just haphazardly thrown together, but as I wandered through and became more familiar and comfortable with them, I soon realized the power of her choices of color, form and stylings. Of course, those familiar with her physical sufferings following a terrible accident and subsequent botched treatments and operations, know that she chose to wear long voluminous skirts and tops to both hide and yet draw attention to her condition while also paying tribute to her heritage. I am not nearly as fearless in my own sartorial choices, but truly admire hers.

Vicki Lang

What a strong woman. Suffering pain as she did and using color and shape to help take her mind off the pain.