Fashion after the Fin de Siecle: A Style Revolution

The fin de siècle was a time of cataclysmic change: rising industry, the age of enlightenment and women’s liberation pulled apart 18th and 19th century Victoriana. Fashion adapted quickly as designers broke away from centuries of stifling tradition with loose silhouettes and experimental designs, allowing both men and women to move freely without constriction, and to find a new freedom of expression through clothing. In the past 100 years since then the fashion industry has soared to dazzling new heights of success. In this new series we will explore the trailblazing fashion designers who led this style revolution, examining their lives, the times they lived in and the powerful influence they have had on the way we dress today.

Even before the 19th century, changes were taking place which would reshape our relationship to fashion. The 18th century Industrial Revolution’s impact on textile manufacture was profound, shifting clothing production from small scale, cottage or home industries to huge, mass manufacture. This meant far more fabric and clothing was being bought and made, moving fashion from necessity to luxury as people had access to more, less expensive goods.

Lifestyles were also changing as the 18th century rolled into the 19th; following the Age of Enlightenment, cultural ideas about religion and the family values it promoted came into question, inviting philosophical enquiries about our place in the world, particularly for women, who sought greater levels of independence and freedom. Even so, in the mid-19th century women still wore the same corsets, bonnets, bustles and petticoats that they had for centuries, while men wore traditional frock coats, waistcoats and top hats. Undoubtedly women’s clothing was the most restrictive and uncomfortable, reflecting their position in society to be confined, contained and aesthetically pleasing for men. One sign that the times were changing was the rising trend for ‘dandy’ men in the 18th and 19th century, who dressed in increasingly feminine, flamboyant clothing, with bows, ruffles and gold jewellery, while some even wore corsets to streamline their waists and accentuate broad shoulders. Led by society gentleman Beau Brummell, the dandy style lingered well into the 20th century.

But perhaps the greatest influence on fashion at the fin de siècle was the rise of the modern city. Paris led the way after being redesigned in 1870 and became a cultural mecca, attracting people from all walks of life, including workers looking for employment and a wealthy elite who spent time in leisure pursuits both within and on the outskirts of the city. Cities across Europe and the United States followed Paris’ example and a new, brimming metropolis was born. Women’s roles were changing in these increasingly liberated societies as they sought greater independence and freedom, both professionally and in free time as the city opened up opportunity like never before.

The conservative 19th century writer Max Nordau saw the rise of this libertarian culture, where the boundaries between men and women were being broken down, as the apocalyptic demise of reason, writing in his book Degeneration, 1892, “We stand in the midst of a serious spiritual national disease, a black plague of degeneration and hysteria.” In contrast, novelist and writer Sarah Grand celebrated the dawn of a new age, coining the term “The New Woman” in 1894, to describe rising numbers of women who were strong minded, educated, sporty and independent. Women’s dress styles began to shift towards the Artistic Style during this time, with long skirts and un-corseted waists, a look captured in the art of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the mid-19th century.

With its already booming textile industry spurred on by the Industrial Revolution, Paris was the first city to establish ‘haute couture’ bespoke fashion at the end of the 19th century, to suit the needs of wealthy clients, many of whom were women. These fashion houses started small, but quickly grew and expanded due to popular demand, an environment which first cultivated fashion houses that would eventually expand from Paris into Milan, London and New York, with many still running today. The haute couture industry in Paris was led by a series of trailblazers including Jeanne Lanvin, whose small hat couturier grew into an emporium with lavishly detailed clothing for women, men and children that explored luxury fabrics and intricate details.

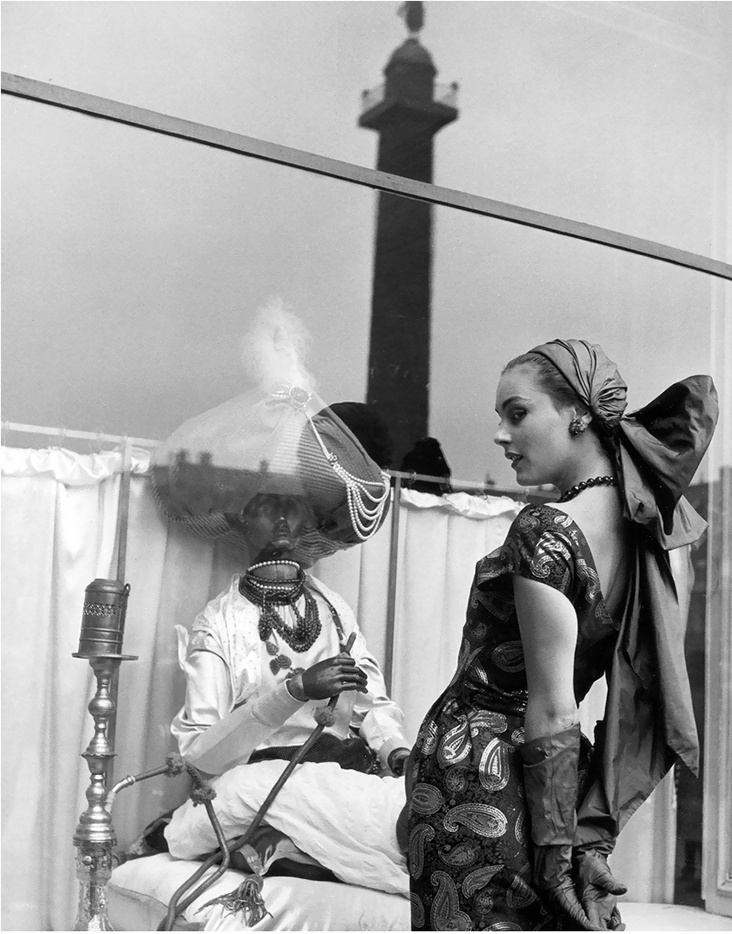

At the same time, Paul Poiret’s unstructured, streamlined designs liberated women from the confines of corsetry with harem pants, sultana skirts and dresses that ripple and fall over the body like water. Famously collaborating with artists including Raoul Dufy on hand printed fabric designs, he introduced dazzling, eye catching motifs that broke with convention and invited room for self-expression through clothing, writing, “I do not want all women to look and dress exactly alike. I want them to be as different in their dress as there are in their personalities.”

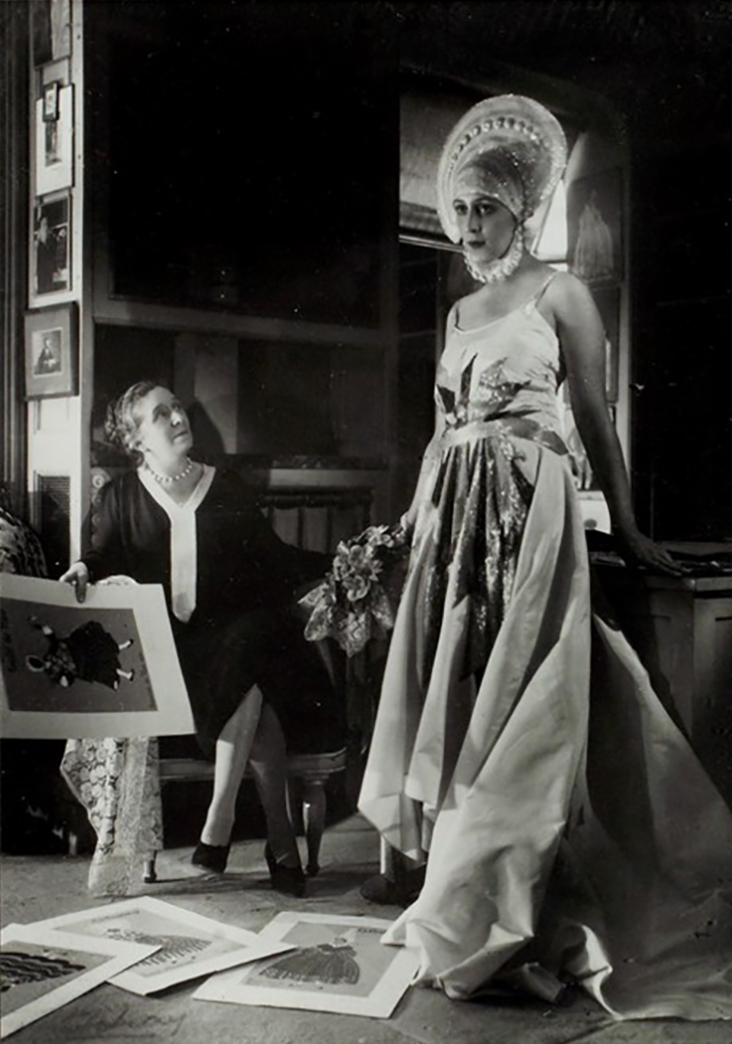

Italian designer Elsa Schiaparelli followed Poiret’s freedom of movement, draping fabric directly on the body and pioneering various popular styles that persist today including wrap dresses that skim the body and visible zippers. Closely linked with Dadaism and Surrealism, Schiaparelli brought playful irreverence into fashion to create ostentatious prints and designs, including collaborations with artists Salvador Dali and Meret Oppenheim.

During and after the First World War, Coco Chanel was instrumental in transforming women’s fashion for a new era, modelling order, restraint and simplicity with clean, masculine lines and a sporty physique which symbolised a new kind of freedom through movement. She wrote, “Look for the woman in the dress. If there is no woman there is no dress.” Her designs came to define the free spirit of the flapper age, with mini-skirts, little black dresses, Breton stripes, dropped waists and cropped jackets, items which are still in production and circulation in various forms today. The androgynous, mannish tailoring she promoted was played out by celebrities and film stars of the time including Louise Brooks and Marlene Dietrich, while her revolutionary use of jersey was outrageous at the time, as designer Karl Lagerfeld points out, “Jersey was men’s underwear material and it was much more shocking in those days because women weren’t supposed to know that men wore underwear. And Chanel made dresses from them.”

By the end of the Second World War Christian Dior had defined a new, more wearable style of cinched waist dress without the corset, lending the 1950s a boost of femininity, a style which still proves popular today. Hubert de Givenchy’s famous Breakfast at Tiffany’s ‘Audrey’ dress launched his career in the same era, earning him a cult following as his fashion for creating understated, minimal elegance highlighted without constricting the female form.

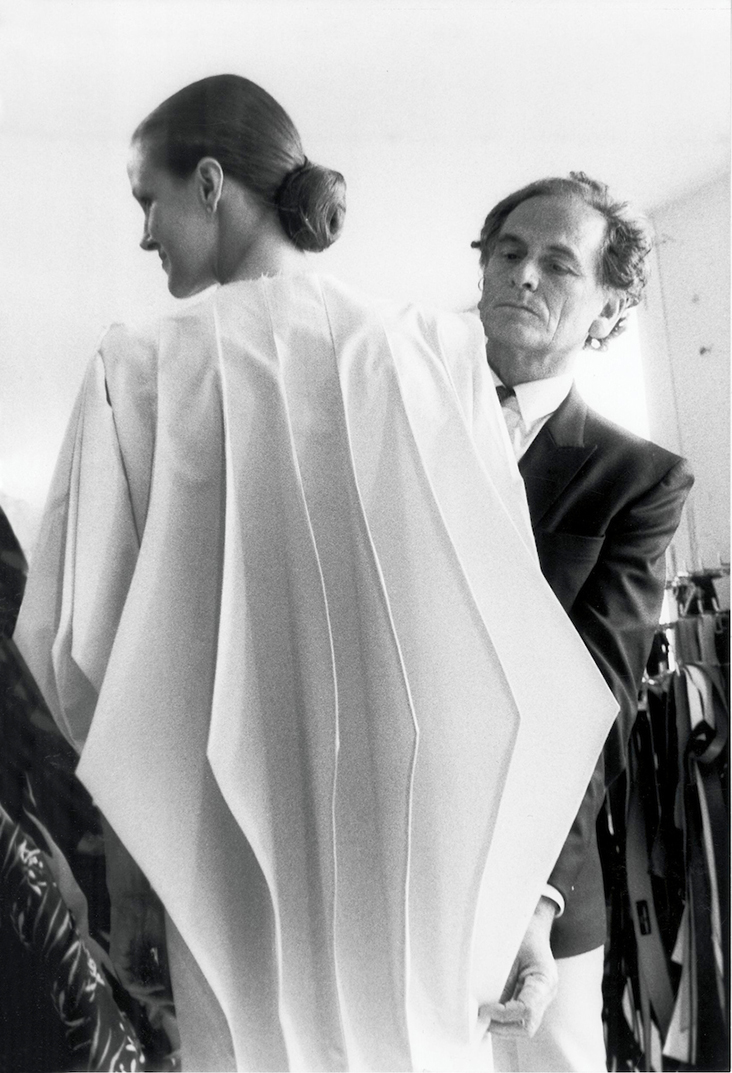

Originally trained as an architect, couturier Pierre Cardin worked with Schiaparelli and Dior before founding his own fashion house in the 1950s. Like Schiaparelli, Cardin’s sculptural designs for men and women pushed the boundaries between fashion and art, with jutting angles and sharp edges that move away from the human body. After visiting NASA he imagined a future universe where humans live on another planet, designing a series of unisex ‘Cosmocorps’ suits for us to wear on Mars, encouraging crossovers between men and women’s clothing for a distant future. More recently, Italian designer Giorgio Armani’s androgynous aesthetic also dissolves lines between men and women’s clothing, with loose fit tailoring that epitomises understated sophistication. He writes, “A woman in a man’s coat is much more sensual than a woman in an evening dress.”

The radical past 100 years of fashion have irrevocably altered the industry’s identity, leading to the freewheeling, madcap universe of free play that is the international phenomenon of fashion today. But as many of today’s designers will testify, it is the spirit of reinvention pioneered by these leaders and many more at the turn of the century that opened up the floodgates, allowing experimentation and adventure to take hold. Join us next time when we will delve into the weird and wonderful world of Elsa Schiaparelli, whose daring designs made her one of the 20th century’s most prominent and ground-breaking designers.

2 Comments

Cassandra Tondro

I love your articles on colors influenced by artists and now the fashion industry. It gives so much depth to the products that you’re offering. Bravo!

Mary Storey

Wow how wonderful to read your piece on fashion history. It is not often we see a retailer pay homage to our fashion history.

I love the color references to art, but this just adds another dimension to your site.

As a university fashion instructor, I have recommended your site for shopping for linen.

Many shoppers may know little of apparel history, hopefully your article will foster an interest to search for more information about various designers and important changes in fashion history.

Keep it coming!