Arts and Crafts: Rooted in Nature

From curling leaf tendrils to jagged wildflowers and scrawny weeds, growing forms were prevalent throughout the Arts and Crafts era, which was firmly rooted in nature. Such imagery came to epitomise the movement, which rejected depersonalised industry in favour of the natural and organic, celebrating our deep human need to connect with the natural world. Locally sourced plants and animals from the English countryside became particularly popular, adorning wallpapers, tapestries, hand printed tiles and stained glass panels with dense, rich patterns that seem to climb and grow into a life of their own. Reflecting on the parallels between art and nature, art critic and writer John Ruskin wrote, “Nature is always mysterious and secret in her use of means; and art is always likest her when it is most inexplicable.”

Pioneering designer William Morris was one of the first in his generation to explore an art borne out of nature. Initially trained as an architect, the young Morris’ interior design firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co., and later Morris and Co., was founded in 1861 in London, providing him with a real chance to integrate natural forms, methods and materials into the design process.

Much like Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelite painters, Morris believed true art came from the direct observation of nature, which he experienced first in lengthy country walks, and in following years as he established a wild garden in his self-designed Red House in Kent, which was decorated inside and out with floral motifs. Morris also collected herbals, 16th century books containing accurate plant and flower studies and their medicinal properties, giving him an extensive knowledge of botany, although he credited the importance of imagination in producing great works of design, writing, “ornamental pattern work … must contain three qualities: beauty, imagination and order.”

Steering clear of overtly pretty designs, he wrote, “…in choosing natural forms be rather shy of very obvious decorative ones, eg. bindweed, passion-flower and the poorer forms of ivy…”, preferring the rugged nature of weeds, which he could transform into striking, angular patterns. In Morris & Co. he was able to revive various medieval techniques including vegetable dyeing to produce indigo blues and madder reds, while promoting bespoke, hand crafted wares such as painted tiles, woven rugs and in-house woodblock printed wallpapers, levelling the field between art and design.

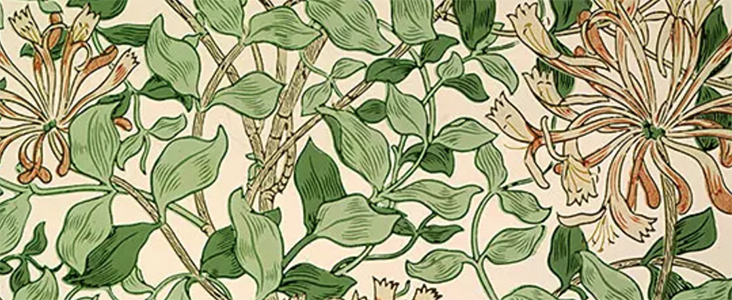

May Morris / Honeysuckle / 1883 / wallpaper design / William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest

Towards the later part of his career Morris moved away from design into the conceptual realms of writing and activism, leaving the next generation to take up the helm. His youngest daughter, May Morris, began working in Morris & Co. in the early 1880s, designing intricately woven wallpapers featuring natural motifs for London’s wealthy elite, including the hugely popular bristling forms of Horn Poppy, 1885, and Honeysuckle, 1883, a mass of tangled stems, leaves and peach blossoms. Her designs were subtle and delicate, revealing a preference for the less beautified, wild charm of countryside hedgerows. She later expanded into needlework, becoming head of embroidery design at Morris & Co. for several years before leaving to focus on her own practice, integrating medieval silk and gold thread into intricately woven pieces featuring tight arrangements of birds, flowers and leaves.

The prolific and influential illustrator, designer and writer Walter Crane was profoundly influenced by Morris’ integration of nature into art. He began his career as a commercial illustrator, rising the ranks to become one of the most celebrated children’s book creators of his generation. Much like the Pre-Raphaelite painters who inspired him, nature was the bedrock for his highly detailed drawings and wood engravings, which set characters from nursery rhymes and children’s stories amongst quaintly organised English gardens and overgrown tangles of weeds. But like the best fairytales, his illustrations often had a dark edge, featuring surreal flowers with faces and grimacing creatures emerging from the undergrowth. Crane’s flat planes of vivid, lush colours surrounded by strong contours became the ideal foundation for his wallpaper and fabric design, which proved commercially popular, featuring the same intricate, linear patterns and sinister undertones of his illustrative work.

As a founding member of the Arts and Crafts Society in 1887, Crane’s preference for lush, vivid plant life was shared with many of his peers, including architect C.F.A. Voysey, who designed some of Britain’s finest country houses, as well as wallpapers, fabrics and furnishings to decorate them. His designs were more quiet and elegant than Crane’s, with his maxim ‘less is more’ made evident in his muted colours and refined, simplified forms. The younger pattern designer Lindsay Butterfield was a self-confessed devotee of Voysey’s designs, taking inspiration from his restrained, open curving forms, yet his colour palette was broader, reflecting a passion for the raw beauty of English flowers as observed in his own garden. He transposed daffodils, sweet peas, poppies, irises and lilies into sophisticated designs, surrounding flowers with dense, curling foliage to give his designs a free, untameable quality.

Ceramicist Ada Louise Powell, born Ada Louise Lessore, initially trained in calligraphy before moving into the field of ceramics, later producing some of Wedgewood’s most popular designs. Establishing a community of artists in the Cotswolds in England with her husband Alfred in the early 20th century, Louise Powell revived hand painted pottery, or ‘art pottery’, which featured delicately hued, carefully structured networks of curling leaves, plants and vegetables that seem to brim with the power of nature’s regenerative energy – she is now regarded as one of the most outstanding ceramicists of the age.

The curling foliage in William and May Morris’ designs paved the way for the famous ‘whiplash’ curls of Art Nouveau, while Voysey and Butterfield’s retrained elegance can be seen in the streamlined forms of Art Deco. After the First World War such lyrical patterning was replaced with Neoclassical order and restraint as an attempt to instil a new societal structure, yet pockets of the style survived through various small scale guilds and factories. By the 1960s bold, floral patterns had returned to celebrate a new era of optimism and decadence, followed by the 1970s flower power, hippie era. Many of today’s designers have reconnected with the moral conscience at the heart of the Arts and Crafts era, recognising how fundamental the connection with nature is to our survival and happiness.

Designers as varied as Dries Van Noten, Consuelo Castiglioni and Christopher Bailey continue to look to naturally derived motifs, which, much like the Arts and Crafts designers, incorporate a subversive edge, as Van Noten explains, “Too beautiful scares me and too pretty becomes a little boring.” Scottish design house Timorous Beasties echoes this mindset, producing decadent floral wallpapers, fabrics and home furnishings in hallucigenic, photoreal repeat patterns and electro bright colours, prompting one art critic to describe their work as, “William Morris on Acid.” For V&A curator Karen Livingstone, the plant forms of the Arts and Crafts era have more resonance today than ever, although the ideas raised a hundred years ago are more pressing, reflecting what she calls, “more fundamental ideas about how to live in … and how to treat the world.”

Join us next time for the final chapter in this series, when we will look in more depth at the ways the rich, lavish history of Medieval culture influenced the Arts and Crafts phenomenon.

4 Comments

Pingback:

2024's Best Garden-Inspired Christmas DecorMarlene Walker

the images are beautiful. have you ever considered working with an artist to produce similar designs printed fabric for upholstery and accessories. (not me).

Nancy Schober Cross

These articles are a delight and yet a pretty good primer of the movement. Thanks for offering this. Gorgeous images too!

Elaine Rutledge

Thank you, Rosie, for a comprehensive and sensitive article. I am looking forward to the final chapter of the series.