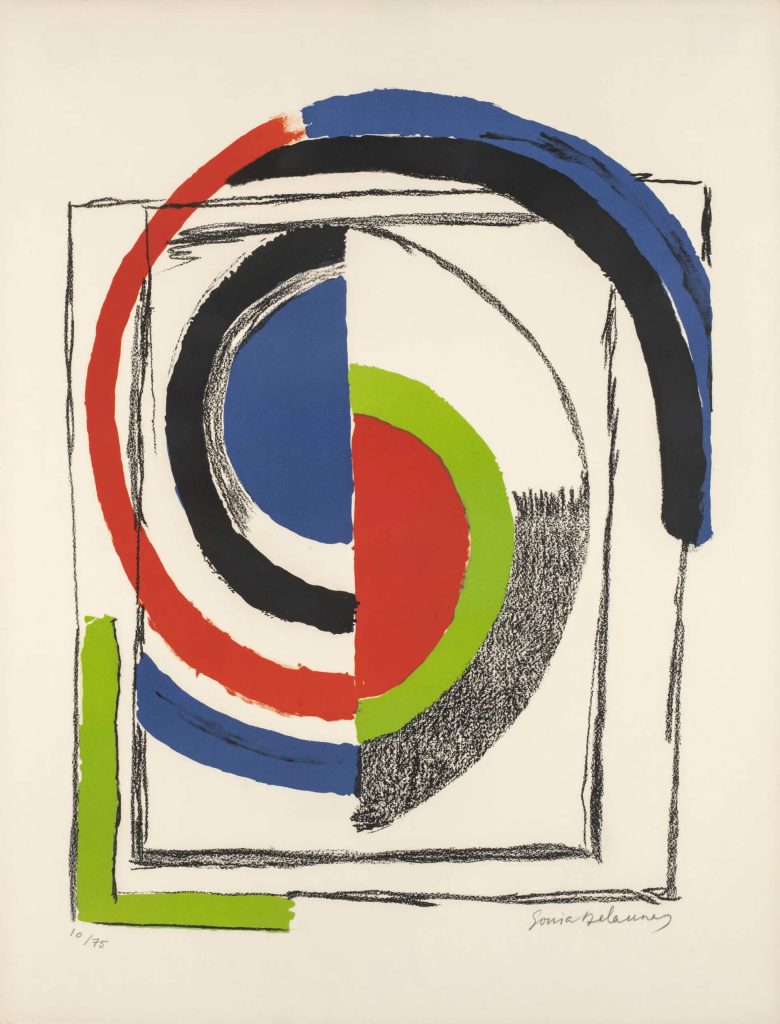

Sonia Delaunay: Wearable Art

The name Sonia Delaunay is synonymous with kaleidoscopic colours and prismatic designs that seem to splinter, shift and dance before our eyes. In a 60 year long career, her daring, vivid Simultaneisme encompassed paintings, textiles, fashion design, costume and interiors, making her one of the greatest pioneers of the Modernist era. While history has favoured her husband’s ‘high-brow’ abstract paintings over her eclectic, decorative approach, in recent decades major galleries and museums have finally woken up to the strength of her legacy, including Tate Modern and The Paris Museum of Modern Art. She said herself in 1978, the year before she died, “What had people been saying about me up to then? Muse of Orphism, decorator, Robert Delaunay’s partner. Then they conceded: “collaborator, continuer … before admitting the work existed in its own right.”

The name Sonia Delaunay is synonymous with kaleidoscopic colours and prismatic designs that seem to splinter, shift and dance before our eyes. In a 60 year long career, her daring, vivid Simultaneisme encompassed paintings, textiles, fashion design, costume and interiors, making her one of the greatest pioneers of the Modernist era. While history has favoured her husband’s ‘high-brow’ abstract paintings over her eclectic, decorative approach, in recent decades major galleries and museums have finally woken up to the strength of her legacy, including Tate Modern and The Paris Museum of Modern Art. She said herself in 1978, the year before she died, “What had people been saying about me up to then? Muse of Orphism, decorator, Robert Delaunay’s partner. Then they conceded: “collaborator, continuer … before admitting the work existed in its own right.”

Born to a poor Jewish family in Ukraine as Sara Elievne Sterne, the young artist experienced a dramatic change in fortune when she was adopted by her wealthy Aunt and Uncle in St Petersburg at the age of 5 and renamed Sonia Terk. At her prosperous private school in St Petersburg Sonia soon discovered a talent for the arts, leaving Russia to study art in Germany. There she first experienced the true spirit of the avant-garde in paintings by the French Post-Impressionists and after graduating at 21, Paris became her new home.

In the newly built, overpopulated city of lights she found a burgeoning, experimental art scene bubbling up with the potency of new ideas. The rebellious, bohemian culture rallied against the conformity of the past and celebrated the dawn of a new era with expressive paint, bold colours and new techniques, breaking down barriers between disciplines. Despite pressure from her family to return to Russia, in 1908 Sonia arranged a marriage of convenience with her friend Wilheilm Udhe, part to ensure her stay in Paris, part to mask his homosexuality. They divorced shortly after in 1910 when Sonia met and fell in love with the young painter Robert Delaunay. In him she had found a soulmate, and was divorced and remarried as Sonia Terk Delaunay.

Together the Delaunays had family money to keep them afloat, setting themselves up as the power couple of the French avant-garde and hosting regular soirees in their city apartment. They were both painters when they met, influenced by Post Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism, but Sonia began moving towards decorative arts and needlecraft. Some have suggested she stepped back from painting so Robert could step forward, but she saw no division between the fine and decorative arts, extending the same ideas into her crafts and her paintings, saying, “For me, there is no gap between my painting and my so-called ‘decorative’ work. I never considered the ‘minor arts’ to be artistically frustrating; on the contrary, it was an extension of my art.”

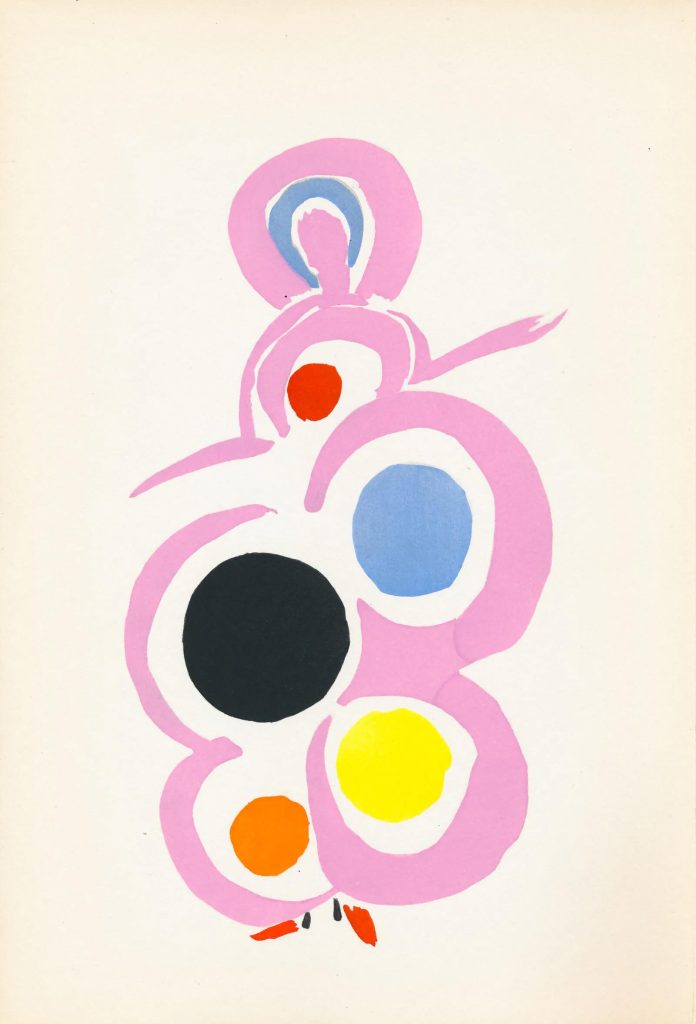

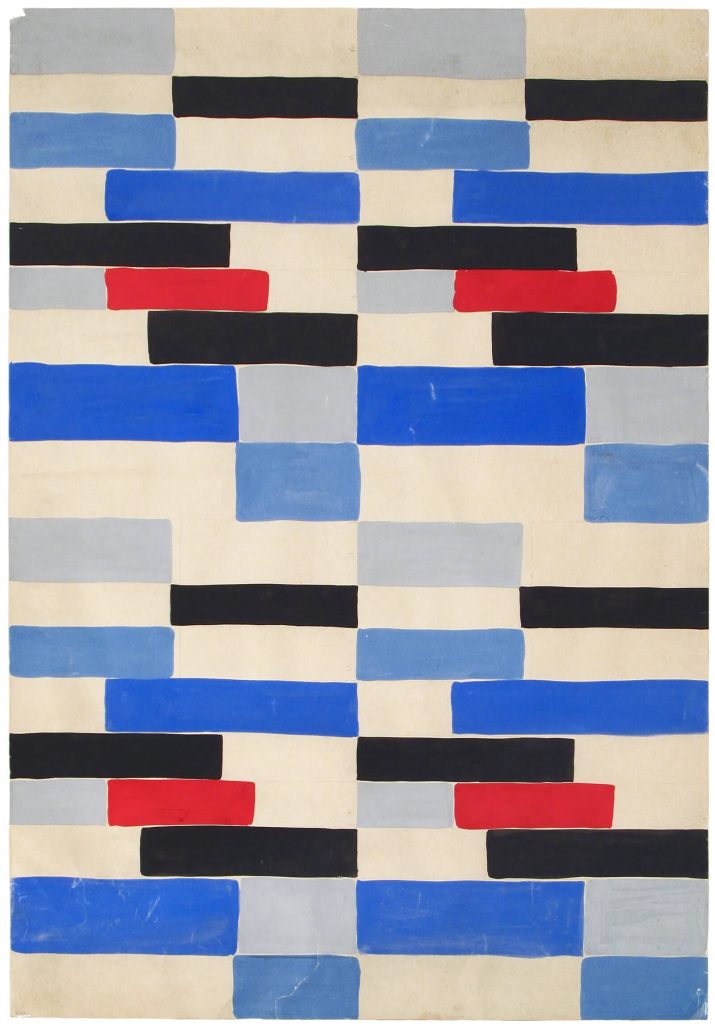

When Sonia’s son Charles was born, in 1911, she stitched a little blanket for her son, and in doing so paid homage to her Ukrainian folk craft roots melded with Parisian avant-garde of her present life. This quilt seemed to mark an important point in Sonia’s work when she moved from the figurative to the abstract, intuitively anticipating what was to become her signature style. She remembered, “When it was finished, the arrangements of the pieces of material seemed to me to evoke Cubist conceptions and then we tried to apply the same process to other objects and paintings.” From the humble child’s blanket came the advent of Simultaneisme, the radical new ideas Sonia and Robert developed together, exploring a patchwork approach to colour by separating it from reality and allowing it blend together in geometric patterns and harmonies that resonate together like music or poetry. Primitivism in Paris, and Neo-Primitivism in Russia brought with them the revival of folk arts and crafts as a reaction against the depersonalised effects of industrialisation and Sonia was keen to invest the rich colour and pattern of her Russian past into her new art.

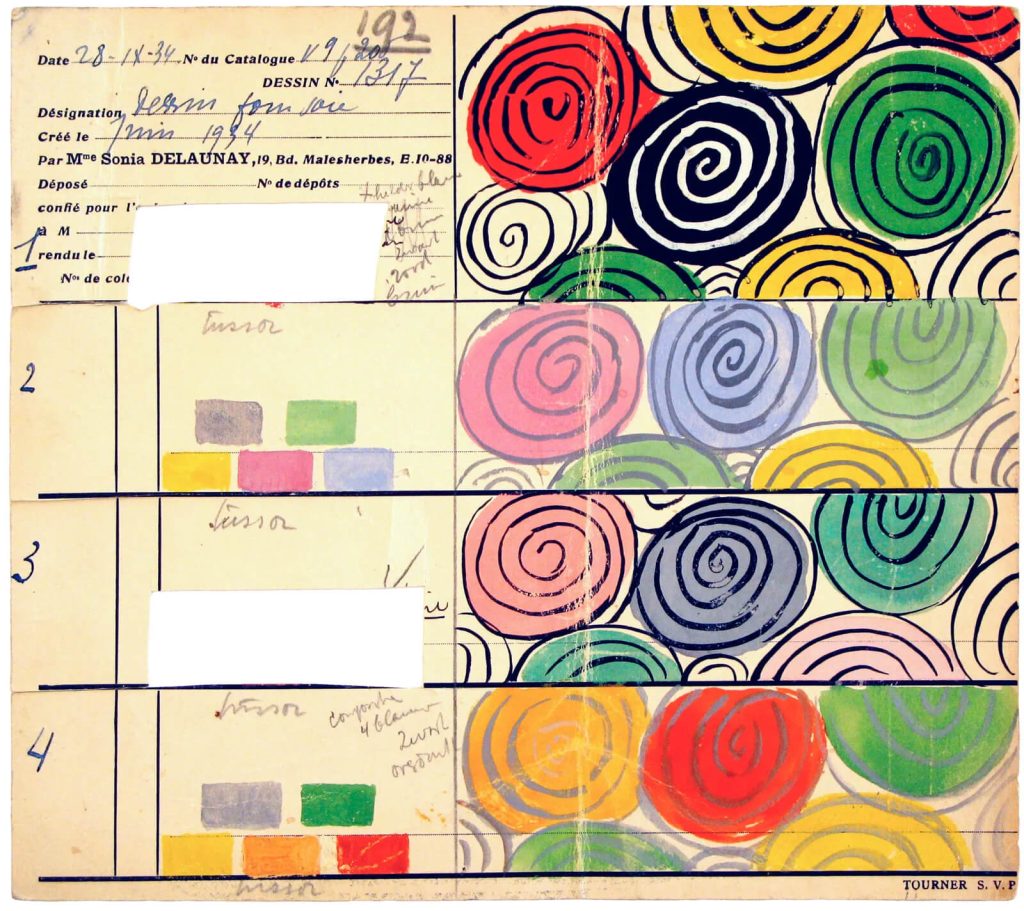

In 1914 whilst Sonia and Robert were on holiday in northern Spain, the First World War broke out. They decided not to return to Paris and instead spent the next seven years traveling and painting within Spain and Portugal. Three years later, after the October Revolution in 1917, Sonia stopped receiving financial support from her family. To further her own interest in applied arts and to create an alternative source of income, Sonia began making costumes for her friend Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. With his support in 1918 she was able to establish a very successful fashion and design house Casa Sonia in Madrid (she later opened subsidiary branches in Bilbao, San Sebastian and Barcelona), selling fabrics for interiors and her own self-made items of clothing.

On their return to Paris in the 1920s Sonia continued to develop her fashion house, producing fabric designs and garments under the clothing label Simultane. The Delaunays’ Parisian apartment became a Simultane showcase, with Sonia’s coloured patterns emblazoned on everything from lampshades and wall hangings to furniture, creating a living art that extended far beyond the confines of the canvas. They again opened up their stylish home on Sunday afternoons to artists, poets, writers and intellectuals and many wore Sonia’s dress designs, including Sonia herself posing as a “living sculpture.” The eye catching patterns of her ‘wearable art’ clothing, went on to attract wealthy high profile clients including American film star Gloria Swanson and the English model Nancy Cunard, coming to epitomise the liberation and freedom of the era. The garments were deliberately cut to suit the real lives of women, allowing them to play sport, work, dance, making her a pioneer in feminism, at a time when women’s roles were finally beginning to shift and loosen.

Sonia also delivered a series of hugely influential lectures including The Influence of Painting on the Art of Clothes in 1927 at the Sorbonne, asserting her belief in the ways rhythms and harmonies of colour could be translated into wearable works of art and give women a greater freedom of expression. In a bid to further blend fashion into art, her clothing designs merged seamlessly with her fabric, as her husband wrote, “Until now, fabrics were dealt with the same way as wallpaper, by the kilometre, with no conception of their future use – or at best, by chance. That was up to the dress designer … Sonia is simultaneous. She gives her conception a perfect creative harmony, by thinking about all the transitions between the ready-made fabric and the final garment.”

In 1925 Sonia was hired to design fabric for the luxury Dutch store Metz & Co. and later made patterns for Liberty in London. In the 1930s, when the textile industry was booming under the influence of mass production she declared, “In this way, fashion will become democratic, and this … can only be welcome as it will raise general standards.” Throughout the 1950s and up until her death in 1979 Sonia continued to paint alongside her successful work as a designer, living out Simultaneisme for the rest of her life.

Modernist culture was almost destroyed by the war and many women artists were written out by male historians in the preceding, oppressive culture of the 1950s, making her part of what writer Axel Madson calls a “lost generation.” Chris Dercon, director at Tate observed, “Sonia Delaunay has been less recognised for her contribution to the history of modern art and abstraction than she deserves, marginalised by an account of the history of art that has prioritised male artists and, at times, positioned her work as decorative.” In recent retrospectives at Tate Modern and Paris’ Museum of Modern Art her divisive, yet hugely influential position on the border between art and design has been celebrated and she is finally receiving her rightful place in history as a trailblazing pioneer in art, design and feminism. Her influence as a designer fed through into many of the most important styles of the Jazz Age and the roaring 20s, and was felt throughout the 1960s when fashion was liberated once again into bold, Op Art prints and mini dresses. Her seamless, simultaneous blend of mediums and the belief that art and life should merge into one can be compared to artists as diverse as Joseph Beuys, Gilbert & George and Marvin Gaye Chetwynd. Curator Cecile Godefroy rightfully states, “She was a …complete artist: dressed by herself, in front of fabric by herself, or a painting by herself!”

6 Comments

Matthew Baines

I love her passion for colour and for movement in her geometric patterns. I also love her continuous link to her childhood experiences in Ukraine and Russia. She reminds me in that sense of Alexander Girard, both of whom used their passion for folk art to influence their Modernist design patterns. I think she was treated unfairly in comparison with her husband for many years, yet she did have a fantastic ability to promote herself as a living artist, some 50 or so years before Andy Warhol did and was a canny enough businesswoman to drop the Russian styling for Parisian when it came to her American audience! I’ve left a link below of my own blog containing my view of her and her work.

https://billingtonpix.com/blogs/news/sonia-delaunay

Ellen Morris

Where do I buy this fabric? Didn’t find a link.

Carol Koch

Sonia Delaunay also designed the most fabulous playing cards deck. Love this bold style. Thanks for enlightening.

Marta Horesovsky

Thank you for this article. I am horrified that as a graduate with a BS in Art from a well known university, I never was exposed to Sonia or her work. I am gratified to read your well done essay! Gee, my education continues at age 79. Being very intrigued, I will research to see more of her work. Maybe there is a way to incorporate her ideas into my quilting. Thank you again! Marta PS In the meantime starting work on my Akira,

Lisa Lentz

Thanks for an inspiring and enlightening essay.

Rosie Lesso

So glad you enjoyed reading it!