Black Mountain College: Learning by Doing

In 1933, an art school like no other was founded near the Blue Ridge mountains of North Carolina: its name was Black Mountain College. While the experimental and progressive art school only lasted for 24 years, its legacy has survived far longer. Black Mountain modelled a new, open-ended and unstructured way to teach liberal arts, subsequently birthing some of the most outstanding voices of 20th century art. Today, over 60 years since the school closed its doors, Black Mountain is still a source of wonder and fascination, particularly at a time when arts education has become increasingly monetized, segregated and elitist. Can looking back at this liberally-minded college open our eyes to the future of arts education, and its possibilities for teaching and learning in a freer and more spontaneous atmosphere?

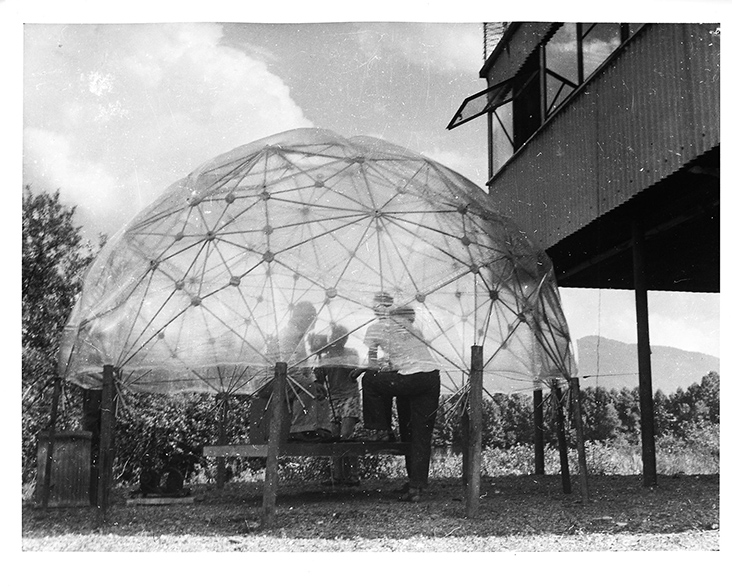

Masato Nakagawa, Buckminster Fuller’s Dome, Demonstration of Plastic Skin. Black Mountain College, summer 1949, (Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina)

Black Mountain College was founded in 1933 by a renegade Classics professor named John Rice. Having recently been dismissed from his teaching post at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida for his alternative ideas, Rice set about establishing a new educational centre, with the arts at its core. Rice took the notion of “learning by doing” first proposed by the American philosopher and social reformer John Dewey as the starting point for this new and innovative educational facility. He argued that making and creative practice should be the root of all education, and could be taught through the three defining principles of observation, judgement, and action. Rice believed students who learned these skills could then take them out into all walks of life, not just the arts.

The timing of Black Mountain College’s emergence happened to coincide with the dissolution of the Bauhaus in Germany. Rice was well aware of the Bauhaus’ reputation for excellence, and this prompted him to employ former Bauhaus professor Josef Albers as head of art at Black Mountain College, even though Albers spoke little English at the time. Albers emphasised taking an open-ended, free-spirited approach, keenly observing the real world for inspiration, and blurring the boundaries between the disciplines of art and craft. He wrote, “We do not always create works of art, but rather experiments. It is not our intention to fill museums, we are gathering experience.” Other faculty members and visiting teachers at Black Mountain included the artist Anni Albers, composer John Cage, dancer Merce Cunningham, painter Willem de Kooning, the artist Josef Beuys and the art critic Clement Greenberg.

One of the most radical aspects of Black Mountain College was its unstructured, and entirely non-hierarchical model for learning. There was no coursework, no timeline, no grades and no fees. Instead, teachers could instruct students in whatever they felt like doing that day, and students were free to graduate (or not) whenever they felt they were ready. Students and staff lived and worked closely together as equals, cooking each other meals, socialising and sharing ideas. They even worked in the surrounding farmlands together, growing produce, harvesting the land, and building furniture and tools together. This creative fusion of art, life, study and play was like nothing that had gone before, a model the art historian Eva Diaz has called, “part of a dynamic process of educational risk.”

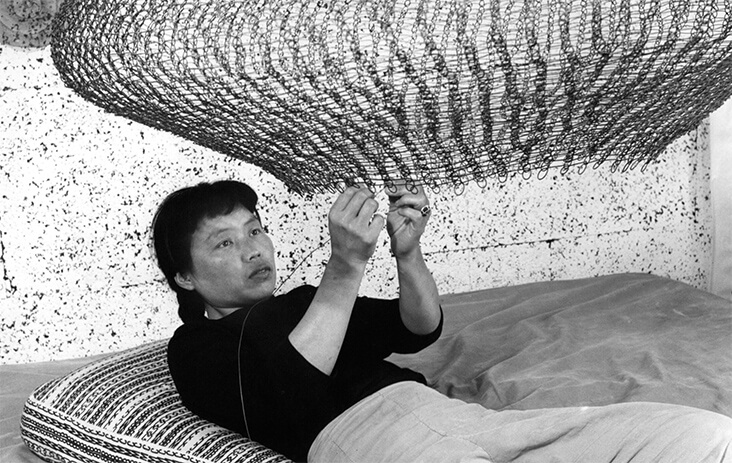

Many students who were immersed in this all-encompassing environment flourished, and went on to become internationally recognised postwar artists, including Robert Rauschenberg, Ruth Asawa, Kenneth Noland and Cy Twombly. Meanwhile, the first ‘happenings’ and performance art emerged out of Black Mountain, fusing art, poetry, dance and music into one. Merce Cunningham later founded the Black Mountain Dance Company during the early 1950s, and worked with Black Mountain artists to create props and set designs.

Sadly, Black Mountain was forced to close in 1957 due to insufficient funding. However, its legacy lives on through the art and ideas that emerged out of the American wilderness, now preserved at the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Centre in North Carolina. In her subsequent publication The Arts at Black Mountain College, 1987, the independent scholar Mary Emma Harris neatly summed up the legacy of this curious and inspirational moment in time, writing, “There was a rare coming together of kindred spirits in an environment receptive to interaction, experimentation, and a lively, imaginative exchange of ideas.”

5 Comments

Wendy Avery

Great post! The Southern Highland Craft Guild was founded in the 1930’s with the goal of keeping “mountain” handcraft skills alive and helping people to make a living via their art and craft, I don’t think that it’s a coincidence that Black Mountain College was located in Western NC. I had no idea of the well known names who “:taught” there. Sound like Hampshire College in MA in the 70’s…graduate when you are “ready”!

Jenn Kirby

I just live about 40 minutes from Black Mountain… Definitely need to go check out that museum!

Diane Kenny

What a truly fabulous article, Rosie! Learning about a school that taught collaborative creativity within community is deeply interesting to me. The areas of dance and musicianship have always relied on working together, and I frequently wonder how much of the resulting work is synergistic by its very nature. For visual artists and writers, the journey is more solitary, typically. I have wondered why. It’s especially fascinating that so many innovators in the arts came out of their Black Mountain experience. Hmmm… was it too cool to be a school?

Carol Buxton

Your articles are so interesting and I always look forward to reading them and learning about artists, color, and concepts. I also love reading the interesting comment above mentioning the town and the library, which I would love to see. Do you have additional information or references to read about the funding of the school, and data about today’s increase in “arts education becoming more monetized, segregated, and elitist.” Thank you.

Patricia Johnson

I LOVE Black Mountain. I took my first solo vacation there in June. I stayed at the Black Mountain Inn which was SO charming and walked (okay hiked) to town twice (which was stupid because I’m handicap). Great people, food, galleries, history, mountain views, shopping, AND if you do go… be sure to check out the southern Highlands Folk Art Center! Swoon! If you love books, there is a library with 2000+ books on art and design history from all over the world. I needed out so hard when I held a book on natural dyes published in the nineteen-teens. Fair warning though… getting a rental car, uber, lyft, or cab… is the stuff of trains planes and automobiles. Nearly ruined my trip but… how could it with so much to love. I was stranded MANY times and though it was stressful (especially alone in a place everyone warns about bears) there was so much to love about the town.