FS Colour Series: AUBURN Inspired by Georgia O’Keeffe’s Rust Red

Warm rust reds like AUBURN Linen tinged many of Georgia O’Keeffe’s most famous paintings, invoking dry autumn leaves, worn out buildings or the barren wilderness of old America. O’Keeffe was one of the most pioneering painters of the early to mid-20th century and she captured the spirit of America during this momentous period in history when industrial change was clashing with a desire to preserve the American outback. Her bold, uncompromising motifs celebrate both strands of thought, coupling rising modernity with sublime visions of nature.

Born on a wheat farm in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, O’Keeffe’s wild childhood would come to influence her for the rest of her life. As a young woman, the anticipation of city life beckoned, and she trained at the Art Institute of Chicago, followed by the Art Students League in New York. A love affair with the photographer Alfred Stieglitz kept O’Keeffe in New York for much of her early career, but her paintings were often focussed on nature, zeroing in on close-up flowers that were bold and dramatic, painted with minimal lines, sensuous folds and angry accents of darkness that grabbed public attention. “I’ll paint what I see,” she wrote, “… what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it – I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

Between 1919 and 1928 O’Keeffe would spend her summers at Stieglitz’s farmhouse in Lake George, on the outskirts of New York. These retreats were important moments in O’Keeffe’s practice, offering her an escape from the intensity of city life. She established her own studio space here and became endlessly prolific, producing around 200 different paintings and drawings inspired by her surroundings. In The Red Maple at Lake George, 1926, O’Keeffe responds intuitively to the depth of red colours in the landscape. She focusses on a single maple leaf, painting it in a weathered patina of rust red and burgundy that suggest the gradual encroachment of autumn. Stark accents of black and white bring theatrical drama into its folds, particularly when coupled with these searing shades of red.

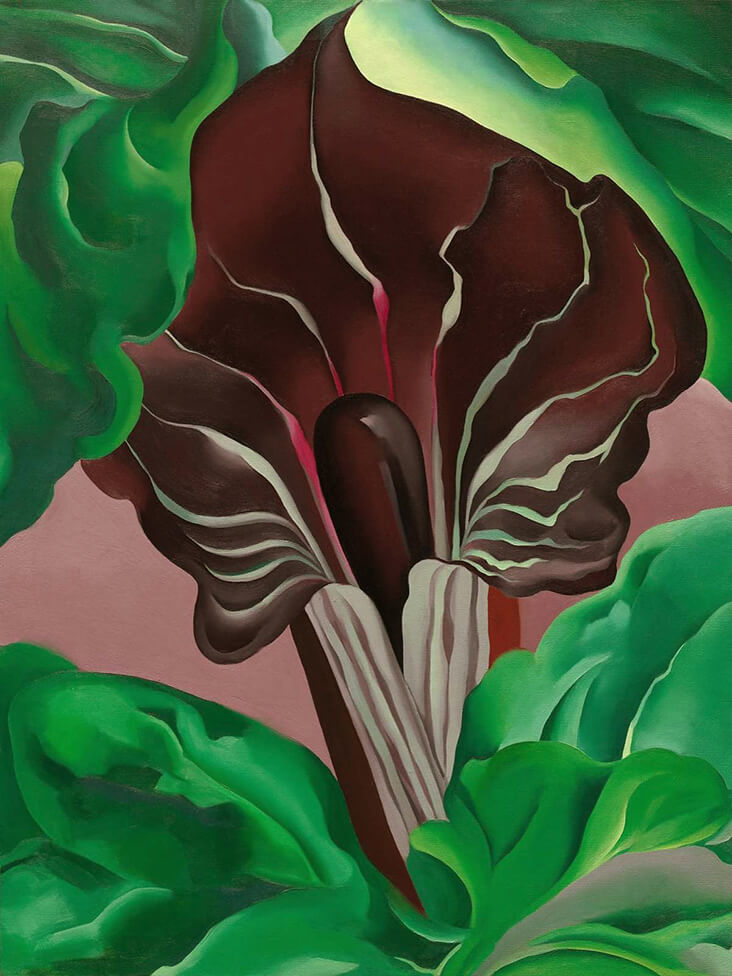

Lake George Barn, 1929 takes in a wider view of the landscape, contrasting man-made constructions with the wild weather around them. Painted in deep autumnal reds, the barns stand out against the encroaching storm overhead, which is a wash of grey and beige. The comforting shade of deep red in these old barns came to signify O’Keeffe’s relationship to the place at Lake George, a quiet safe haven from the rugged surroundings, yet perhaps also an escape from the stresses of city living in New York. The slightly later Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. 2, 1930 is one of O’Keeffe’s last series of flower paintings made in response to the landscape of Lake George; she paints the strangely sculptural volume of the plant with warm burgundy tones, made all the more striking when enveloped in acid-sharp green leaves.

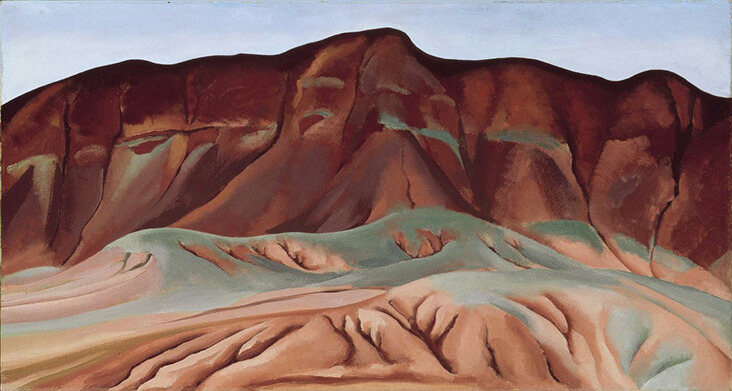

From 1929 onwards O’Keeffe began making regular trips to northern New Mexico, a place she came to call “the faraway.” Her relationship with New Mexico gradually evolved into an intimate bond, particularly when she later relocated there to live full-time. The landscape here had a profound impact on O’Keeffe’s career as she began painting the vast, expansive mountain ranges and craggy, dry rocks with dusty shades of umber, peach and red. Purple Hills Ghost Ranch – 2 / Purple Hills No II, 1934 conveys the barren, sandy wilderness of New Mexico with deep red, maroon and flesh tones that seem to ripple and fold into one another like fabric, opening out wide across the horizon. This desolate, isolated place of awe and wonder became an enduring obsession for O’Keeffe, and many would argue it was here that she was able to fully consolidate her practice, and cement her place in history.

2 Comments

Vicki Lang

O’Keeffe’s paintings have been such a standout for decades. The colors of the desert of New Mexico are classic in her paintings.

Rosie Lesso

Yes indeed – thanks for the comment!