FS Colour Series: ALLURE Inspired by Paul Cezanne’s Sky Blue

Soaring shades of sky blue like ALLURE Linen dominated Paul Cezanne’s late paintings, filling them with the crisp vitality of the Mediterranean coast. By now settled in his home town of Provence, the art Cezanne made in the last decade of his life are now considered his greatest contribution to the history of art, cementing his place as the great father of modern art. He obsessively painted the Provencal landscape over and over again as a shifting tapestry of pastel blues and sandy beiges, merging sky and ground into one prismatic whole. “I think I could be occupied for months without changing my place,” he observed of Provence, “bending a little more to the left or right.”

Cezanne was born in Provence in 1839, but he spent much of his early adult career living in and around Paris. There he mingled with the Impressionist painters and took part in several of their ground-breaking displays that broke with tradition, moving away from the stuffy traditionalism of the Parisian Salon towards a new world of avant-garde modernism. Much like the Impressionists, Cezanne enjoyed painting en-plein-air, but in contrast with the feathery lightness of fellow Impressionists including Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, Cezanne’s works from this period already had a heavier, sturdier and more sculptural quality that was moving towards Post-impressionism.

This separation between Cezanne and the Impressionists only grew wider as the years rolled on, and Cezanne became increasingly reclusive, retreating into a self-imposed exile that, however hard, would prove fundamental to the development of his mature art. From the 1880s onwards Cezanne became obsessively preoccupied with the Provencal landscape of his childhood, capturing its dry, sun-baked scenery with pastel toned shades of blue and orange contrasted with vibrant green. In Houses at L’Estaque, 1880, the dazzling azure blue sky seems to bleed into the sandy rock faces below, tinging it here and there with its constantly roving light. The later painting The Gulf of Marseilles Seen from L’Estaque, 1885 typifies the colour scheme of Cezanne’s late art, with a solid stretch of blue sea dominating the scene, while wood-toned houses in the foreground are stacked over one another like building blocks as they nestle into the greenery around them.

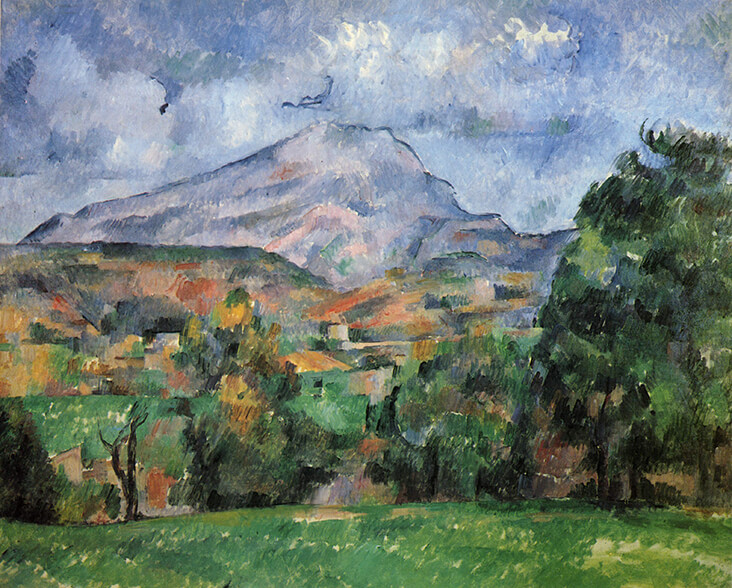

1886 was a significant year for Cezanne; he married his long-term partner Hortense in April, and in October his father sadly passed away. In the years that followed this deepening state of maturity seemed to profoundly affect Cezanne, pushing him to create works of art with an iconic grandeur and monumentality. The ancient, enduring outline of Provence’s Mont Saint-Victoire was a defining feature of Cezanne’s most mature art, sometimes standing strong and proud like an ancient ruin, other times disintegrating into the land and sky around it with the fluidity of water. In Mont Saint Victoire, 1890, dazzling blue sky weaves in and out of patchy clouds, scattering its colours onto the hefty mountain below, and continuing to ripple in patches through the lush green undergrowth.

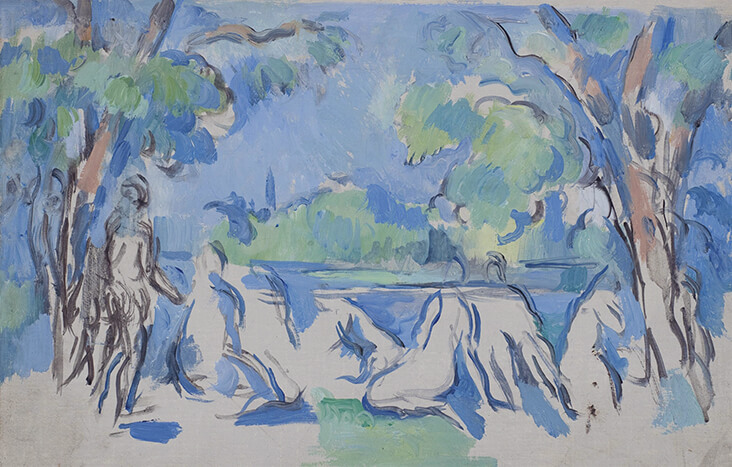

Between 1902 and 1906 Cezanne embarked on his most ambitious project yet, to paint a series of three large-scale, multi-figure paintings with nude women situated in an arcadian landscape. He made a vast series of studies in watercolour which allowed him to experiment freely with various compositional motifs before settling on a final layout, and these fresh, vital and expressive studies each have their own unique character traits. Study for Bathers, 1902-6 is awash with great swathes of blue that encircles the female bodies, drenching them in the paradisiacal light of Provence that had Cezanne hooked for the last decade of his life. In Cezanne’s final oil paintings of The Large Bathers, 1906, the same dazzling shade of blue fills two-thirds of the canvas, flickering in and out of shadowy clouds with the impermanence of air, in stark contrast to the heavily grounded, classical figures below, who seem to carry with them the weight, permanence and history of art.

Leave a comment