Colour, Pattern and Expression: Fabric in the Avant-Garde

At the turn of the 20th century artists increasingly broke away from the real world, heightening the visual and emotional impact of colour, pattern and texture. Fabric was still a vital tool for artistic exploration but its depiction became ever more varied and experimental, from the flattened, Oriental forms of the Intimistes to the broken shards of Fauvism and Cubism, as artists reworked and reimagined the once traditional trope of drapery and clothing.

Both the French Intimiste painters Edouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard had a fascination with interior space, which inevitably led them towards the painting of patterned fabrics, textiles and home furnishings. Vuillard lived with his mother for much of his life and she worked in their home as a seamstress, leaving trailing scraps of fabric around their Parisian home which would make their way into his art.

His paintings capture quiet, dimly lit interior views, enlivened with dappled patches of richly decorative pattern and texture. In Misia et Valloton, 1899, an array of clashing pattern jostle for attention, from the young pianist Misia’s thick, sumptuous tweed coat and brilliant yellow silk necktie to the flat blue jacket of the painter Felix Valloton behind her. Space is closely cropped and reduced to a shallow, low-relief surface, almost rendering the entire scene an abstract, decorative design. Le Pot de Fleurs (Pot of Flowers), 1900 takes this approach a stage further, rendering a simple pot of flowers as flat and decorative as the patterned blue chair and striped brown cushion beyond, making it difficult to distinguish one object from another.

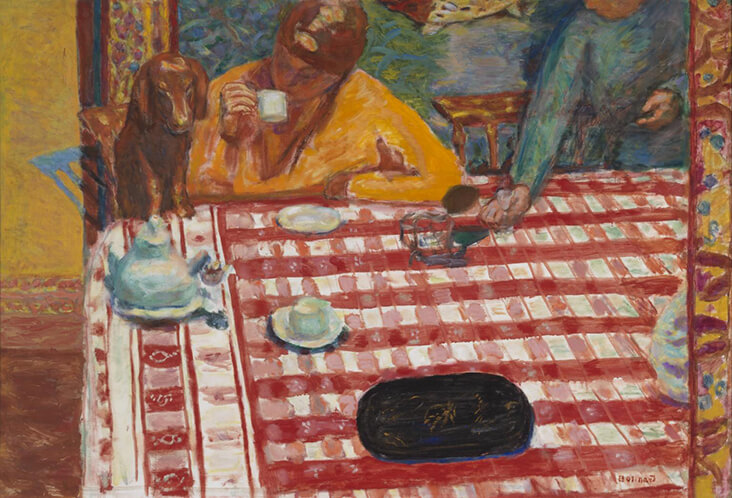

Like Vuillard, Bonnard’s paintings invest magical wonder into the ordinary and every day, heightening and exaggerating its dramatic impact through vivid, intoxicatingly bright colour and dappled patches of paint. The dazzling Coffee, 1915, is one of his best-known paintings, transforming the simple view across a tabletop into a riotous celebration of pattern and light. The red-and-white chequered tablecloth takes centre stage, tilting upwards towards us with distorted perspective to amplify its flat, decorative pattern, while peripheral figures are pushed outwards to the edges of the scene and cropped from view.

Nude in the Bath, 1925, plays with the traditional subject of the bathing female nude, updating it for the modern era with an unusual cropped design, where anonymous women are only partially seen as fleeting, spectral traces in pallid shades of pale pink and blue. Once again, Bonnard makes textured fabrics the main subject, as our eye is immediately drawn to the vividly patterned yellow bath mat below, before travelling up to the crumpled pile of clothes and shimmering translucent curtain beyond where light filters through.

Like Vuillard and Bonnard, French Fauvist painter Henri Matisse was fascinated by fabric and printed textiles, an interest that began in childhood with his family, who had connections to the textile industry of north-eastern France. An avid and obsessive collector, he gathered all manner of fabrics throughout his career, from his early days as a student in Paris to his later years once he had settled in Nice – his vast archive included African wall hangings, Turkish clothing and Parisian textiles.

To create early paintings such as Seville Still Life, 1911, he would throw his textiles over domestic objects, mixing them up to create a cacophonous arrangement of colour, before painting them in a cropped view of shallow space. As his style expanded to become freer and more adventurous Matisse would eventually abandon any sense of perspective, treating all objects, people and textiles as one flat area of integrated pattern, as seen in the masterful Purple Robe and Anemones, 1937.

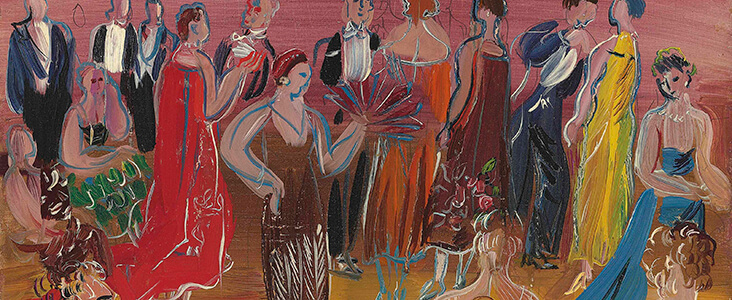

Matisse’s fellow Fauvist, the French painter Raoul Dufy also had a longstanding love of fabric, one which would eventually drive him towards creating his own printed textiles for the esteemed Parisian couturier Paul Poiret. His paintings and prints had a distinctive lightness of touch, capturing energised movement with airy, floating lines and gestural pops of colour. In the lively, spirited Reception, 1940, he fills his scene with swishing and swooping drapes of intoxicatingly bright fabric that shimmer across the room and spill out onto the floor, celebrating the inimitable joie de vivre of the Parisian 1940s, even against the backdrop of war.

Feature Image: (Detail) Raoul Dufy, Reception, 1940

2 Comments

Rosemary Antel

Thank you for the wonderful selection of images by all my favorite artists! I was especially pleased by the image Edouard Vuillard, Le Pot de Fleurs (Pot of Flowers), 1900 as I don’t think I have seen it before. The more subtle colors are very inspiring for art of any kind.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you – they are some of my favourite artists too. I always enjoy looking at Vuillard’s mysterious little paintings – there is so much to discover in them!