Art into Life: The Radical Textiles of Liubov Popova

“No artistic success has given me such satisfaction as the sight of a peasant or a worker buying a length of material designed by me.” Liubov Popova

Russian Constructivist Liubov Popova was a force of nature, expanding her creative ideas across painting, theatre set design and textiles. But many would say the bold, graphic power of her fabric design is her strongest and most influential legacy. Breaking free from the floral prints of Russia’s past, her daring, angular edges and striking, simplified colours came to typify the aesthetic of Russia’s Soviet era. Moreover, her desire to merge “art into life” by integrating avant-garde designs with the industrial production of fabric allowed her to bring her art into the lives of ordinary people, an accomplishment she greatly cherished.

Born into a prosperous Russian background in 1889, Popova showed early artistic promise. Formal art lessons began at the age of 11, followed by training in Moscow’s School of Painting and Drawing. Widely travelled throughout her youth, she was as much inspired by the Italian Renaissance as French Impressionism and Russian icons. In 1912 Popova travelled to Paris to study with the Cubist painters Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger and it was here that she first began to dissect objects with a crude language of angular geometry – aspects of industry appeared in her work including cogs and wheels.

Returning to Russia burgeoning with new ideas she soon befriended a likeminded set including Vladimir Tatlin, Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, before becoming an active member of the Constructivist/Productivist art group, who shared a unified belief that art and industrial production should be merged into one. Rejecting traditional art forms for their ‘bourgeois elitism, ’ the writer Osip Brik summed up their ethos in his essay From Picture to Calico Print, 1924, noting, “The art culture of the future is being made in the factories and workshops, and not in attic studios.”

Popova was first drawn towards textile design in the early 1920s, at a time when the industry was on its knees. Years of war and revolution had all but destroyed Russia’s once flourishing textile trade, and most of the fabric being produced was plain in design. In a bid to inject new life into the industry, an open call went out in Russia’s Pravda newspaper in 1923, encouraging artists and designers to step in and produce designs for the First State Textile Printing Works in Moscow. Seizing the opportunity with both hands, Popova stepped forward to work with Ivanovo textile factory, along with her close compatriots Varvara Stepanova and Alexander Rodchenko.

Though they were refined in aesthetic, the patterns we now see associated with Popova’s name were the result of hard-won labour, as she produced thousands of sketches for possible designs – only around fifty went into final production. A descriptive passage published in LEF, the journal of the ‘Left Front of the Arts’, shortly after Popova’s untimely death in 1924 described her work ethic: “Popova was a Constructivist-Productivist not just in word, but in deed… She would spend days and nights over her designs for cotton prints, trying to bring together in one creative act the demands of economy, the laws of design and the mysterious taste of the Tula peasant woman… To hit upon a simple cotton print was to her incomparably more appealing than to curry favour with the pretentious intellectuals of pure art.”

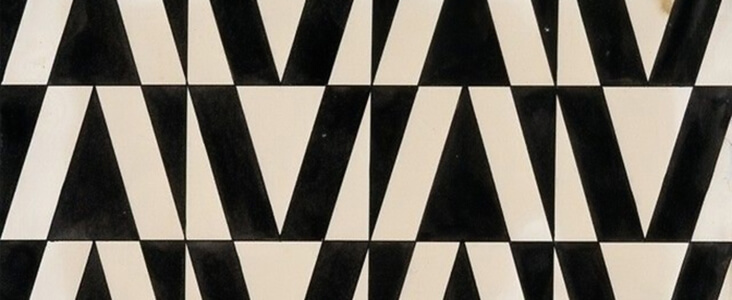

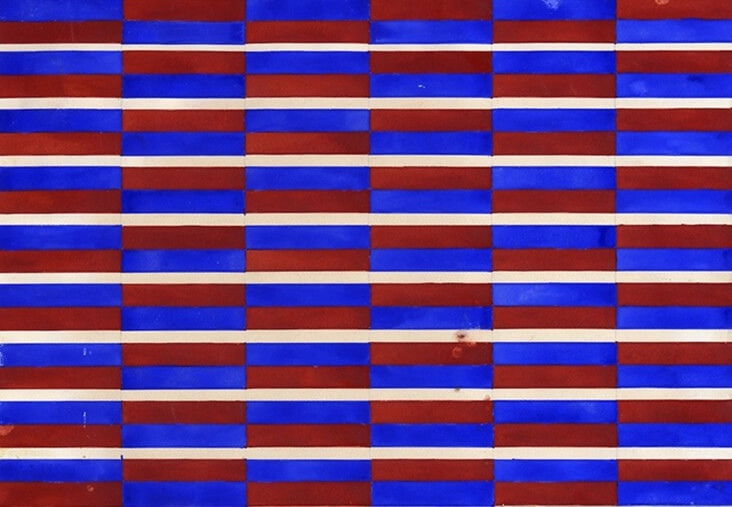

Economic in style, her stylised designs echoed the refined geometry and ‘spatial force constructions,’ in her earlier paintings, but with a greater emphasis on flat forms, pared back colours and dazzling, eye-catching motifs. All designs were made by hand using stencils and rulers, prioritising a machine-made aesthetic. Popova particularly favoured orthogonal forms with a balanced, clear structure, including stripes, right angles and dazzling zig-zagged straight lines to create dynamism and energy, which were sometimes intersected with circles and triangles. The inclusion of black and white elements created even more drama and visual impact.

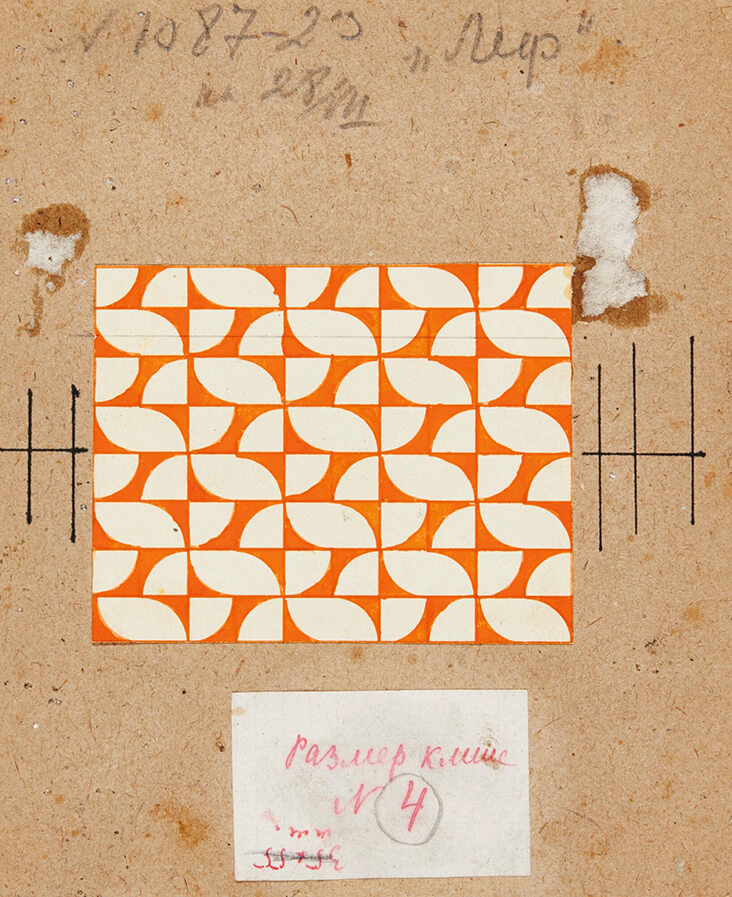

Liubov Popova textile design in orange and white, which was used to illustrate writer Osip Brik’s article ‘From Easel Painting to the Printed Fabric’, 1924, image via Sotheby’s, London

Politically, Popova’s patterns were deliberately free from any references to class or social status, ushering in a new ethos of freedom and equality. In one of her most famous designs Popova made a repeat pattern featuring a simplified version of the hammer and sickle insignia, the symbol of the new Communist state in Russia, which represented the union of the peasant and the industrial worker, demonstrating her allegiance to the cause.

Although Popova died prematurely at the age of 35, in this short time she achieved her desire to create ‘wearable art’ and produce artworks with a shared, collective ethos, living out here belief that art is for everyone. Because of their radical and progressive nature, Popova’s Constructivist textiles took a while to catch on, but today it is clear to see the influence her textiles have had on some of today’s most popular designers, from Anna Andreeva’s precisely mathematical arrangements to Orla Kiely’s dazzlingly simple motifs.

2 Comments

David Unruhe

I love Popova’s designs. (I first encountered her work at this 2009 exhibition: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/rodchenko-popova.) But is actually possible to buy the fabrics? I especially like the blue circles with black and white zigzags (shown above) – and would love a shirt made with that fabric.

A. She

How serendipitous! About a decade or so ago I thrifted some random orange and white canvas that was originally printed for MoMA I believe. And would you know it’s the orange and white design shown here! I never had any info on it, but have used it in my design classes. Thank you for sharing!