Agnes Martin: Mystic Minimalist

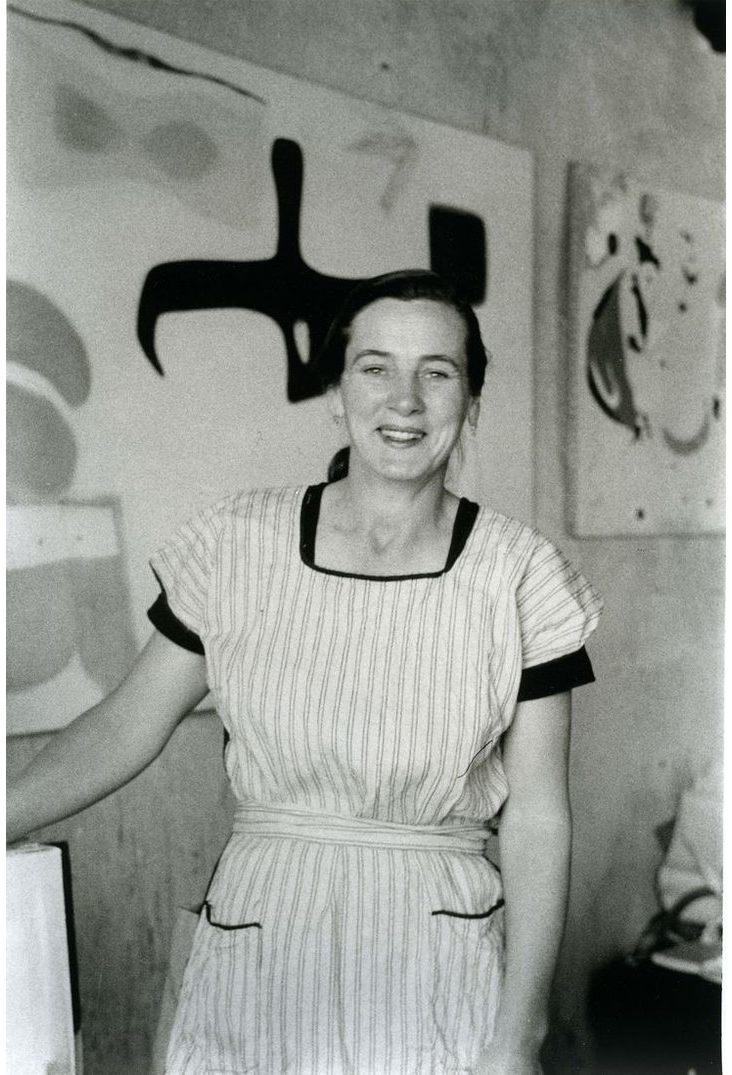

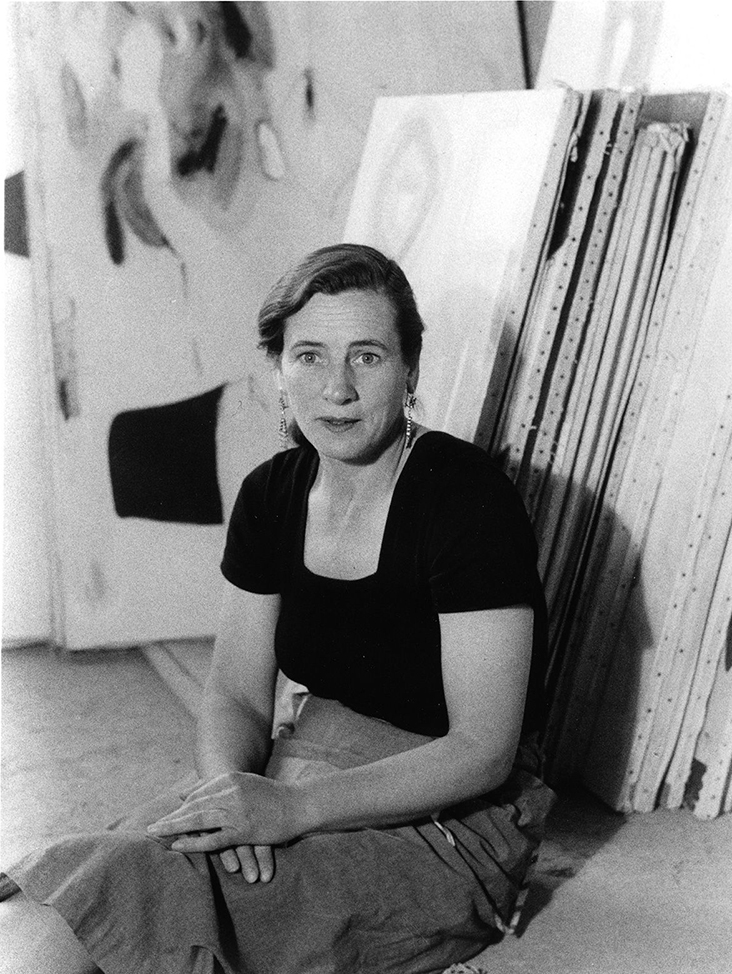

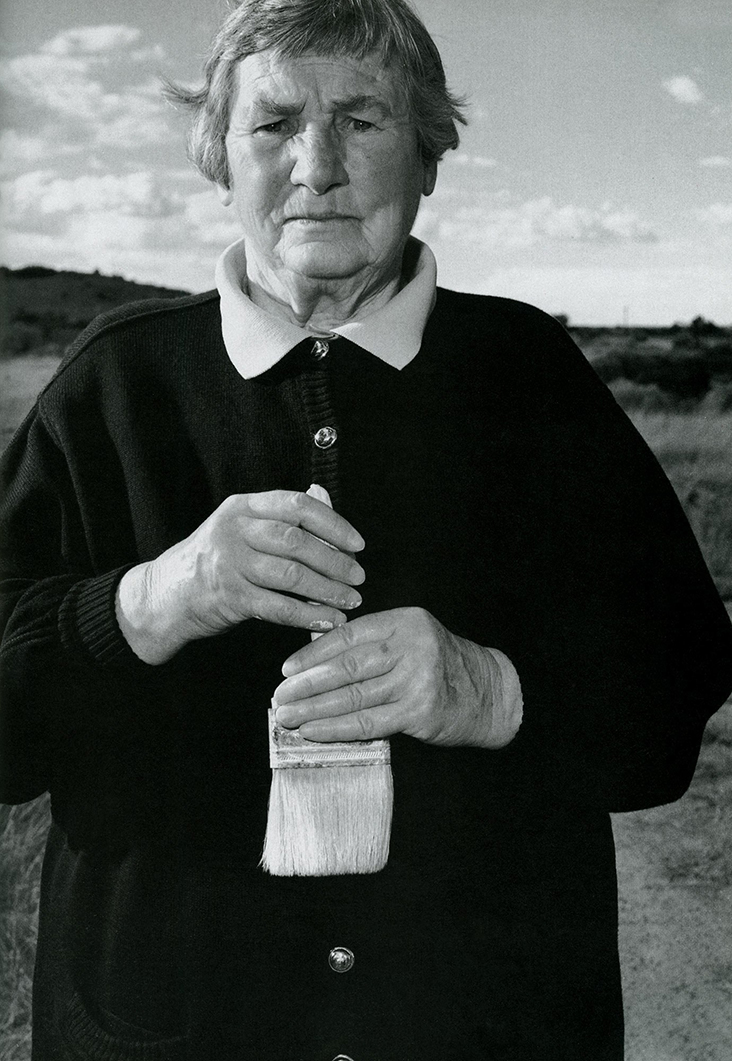

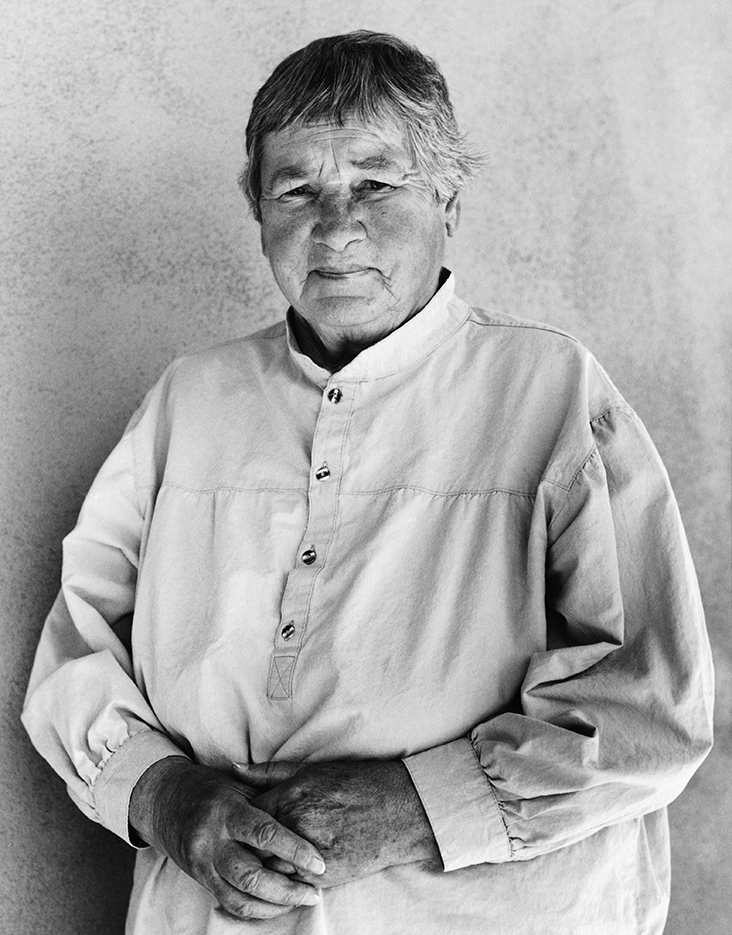

Agnes Martin photographed in her studio by Mildred Tolbert / c.1955 © the Mildred Tolbert Archive Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos

“My paintings are not about what is seen. They are about what is known forever in the mind.”

Agnes Martin’s world is one of order and tranquillity, as minutely patterned grids and ruler straight bands expand across vast surfaces suggesting wide open space. Yet there is also sensitive musicality at play as lines tremble and colour relationships become vibrating rhythm, tapping into the profound realms of human spirituality. Martin’s world renowned, huge Minimalist canvases can be found in major museums and collections across the globe, but even so, in the art historical canon the subtleties of her mystic, inner world have tended to be overshadowed by the bravado of her male contemporaries. Yet the courage and bravery of her closely intertwined art and life have made her an iconic figure, whose progressive ideas continue to invade the practices of countless artists working today. Tate Modern’s director Frances Morris reflected on her life’s legacy, calling it the hard-won result of “huge personal and spiritual struggle.”

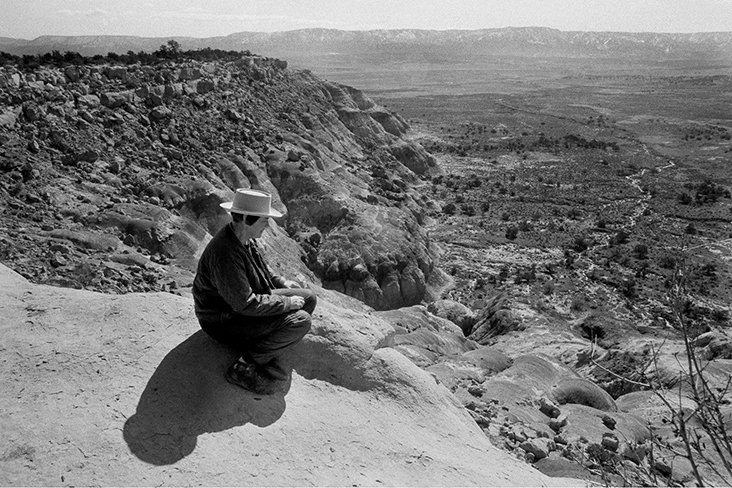

Agnes Martin in her studio in Taos, New Mexico in 1953. Mildred Tolbert / 1953 / The Harwood Museum of Art, Gift of Mildred Tolbert © Mildred Tolbert Family

Martin was raised on an isolated farm in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan by Scottish Presbyterian settlers, whose firm religious beliefs would come to inform the spirituality of her art later in life. Her father, a wheat farmer, died when she was two, leaving her mother as the sole provider, who sold real estate to keep the family afloat. Martin found her mother stern and authoritarian, leaving an emotional void between them which would never truly be filled. When the family relocated to Vancouver the athletic young Martin considered becoming a professional swimmer, trying unsuccessfully to join the Olympic team. Instead she trained as a teacher in Washington, later enrolling to study fine art at the Teachers College of Columbia University in New York in 1941. She spent the next 15 years moving between various training schools in New York and New Mexico, pursuing work as an art teacher and continuing to paint, though she destroyed most of her early work. It was at Columbia that she first encountered the ideas of Zen Buddhism and Taoism, whose calm, orderly sense of structure would stay with her for the rest of her life.

Throughout the 1940s and 50s Martin spent increasing amounts of time painting, while living between New York and the Pacific Northwest, where the dry, barren landscape of her childhood kept pulling her back. In 1947 she took part in an artists’ study programme at the Harwood Museum in Taos, New Mexico, befriending various local artists including Beatrice Mandleman and Louis Ribak. Nearly a decade later, Martin returned to New York as encouraged by gallerist Betty Parsons, where she settled in the New York artists’ community known as Coenties Slip, a series of decrepit studios on the waterfront of lower Manhattan. There she found a lively hub of free spirits who would go on to become some of the city’s most revolutionary young artists, including Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Indiana and Ellsworth Kelly. Martin was 45 at the time and a good 10 years older than her contemporaries, lending her a certain revered status amongst them. She also found the environment refreshing and invigorating, filled with what she called “humour, endless possibilities, and rampant freedom.”

The Coenties district was popular with the gay community and Martin found she was able to be more open about her own sexuality here, embarking on several relationships with women including fibre artist Lenore Tawney and the Greek sculptor Chryssa, though in the wider public she often denied being a lesbian, keeping her personal life intensely private. Yet when once asked about her role as a feminist in an interview in her later years, Martin obliquely referred to her ambiguous sexuality by retorting, “I am not a woman.”

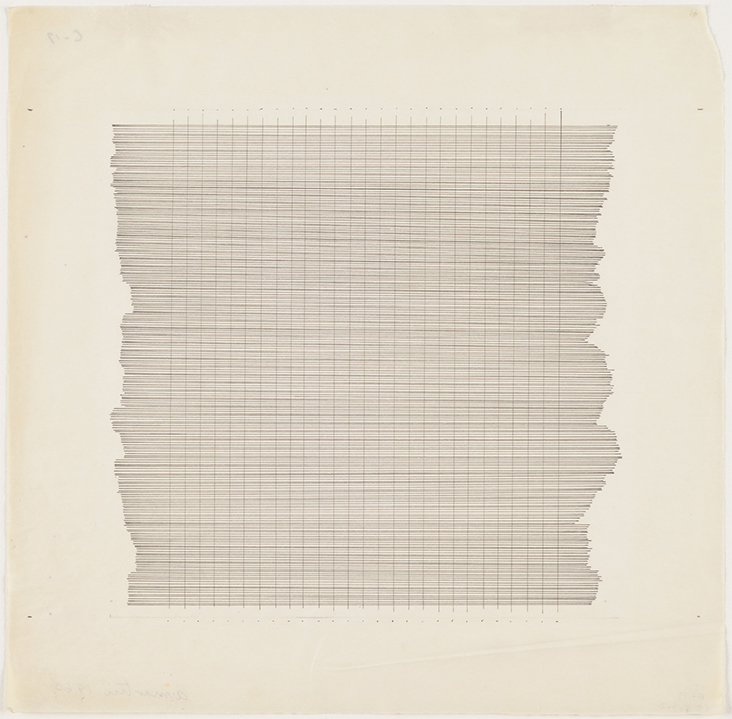

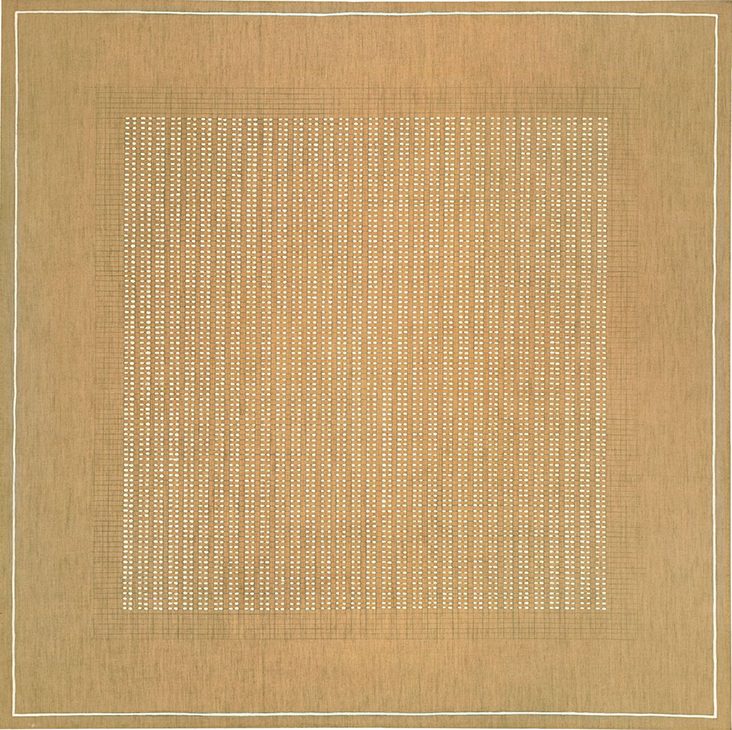

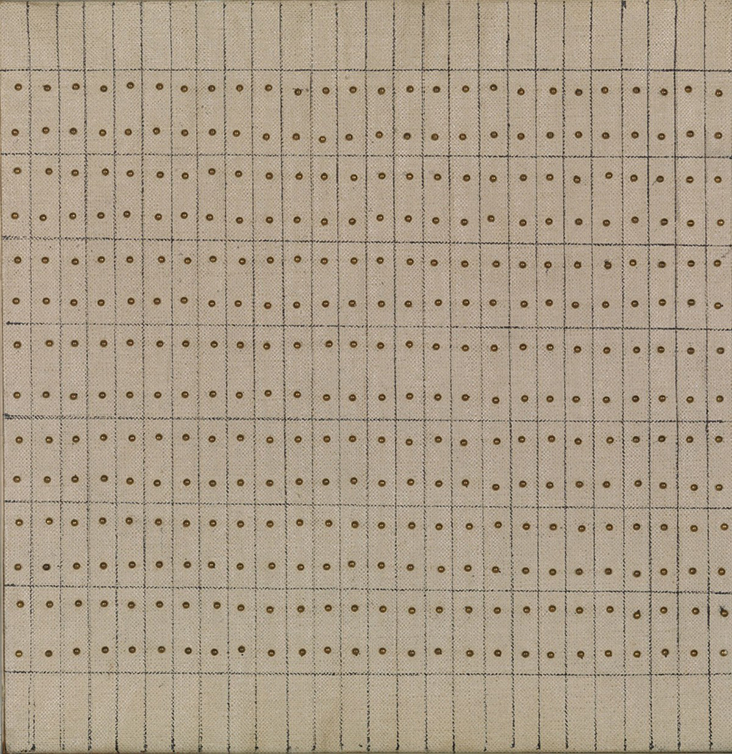

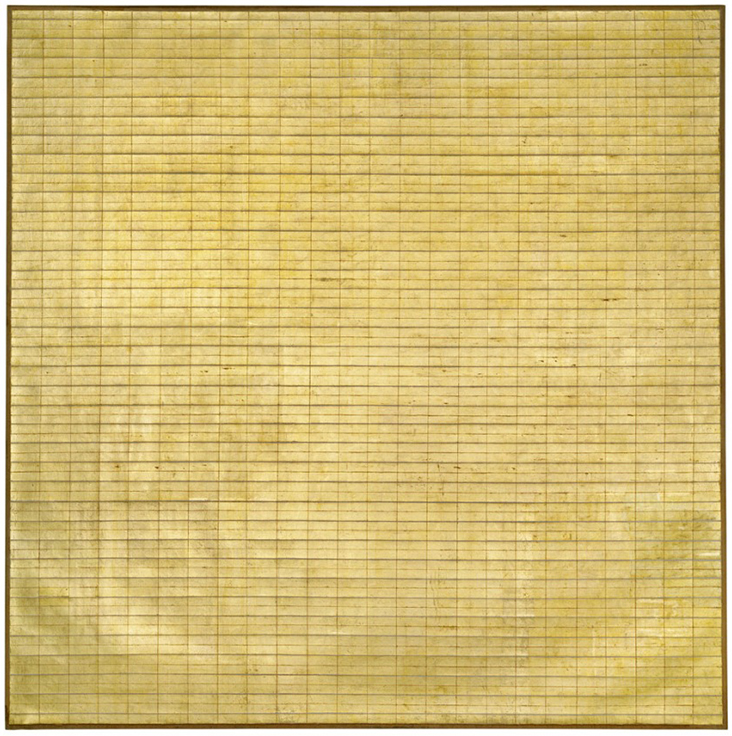

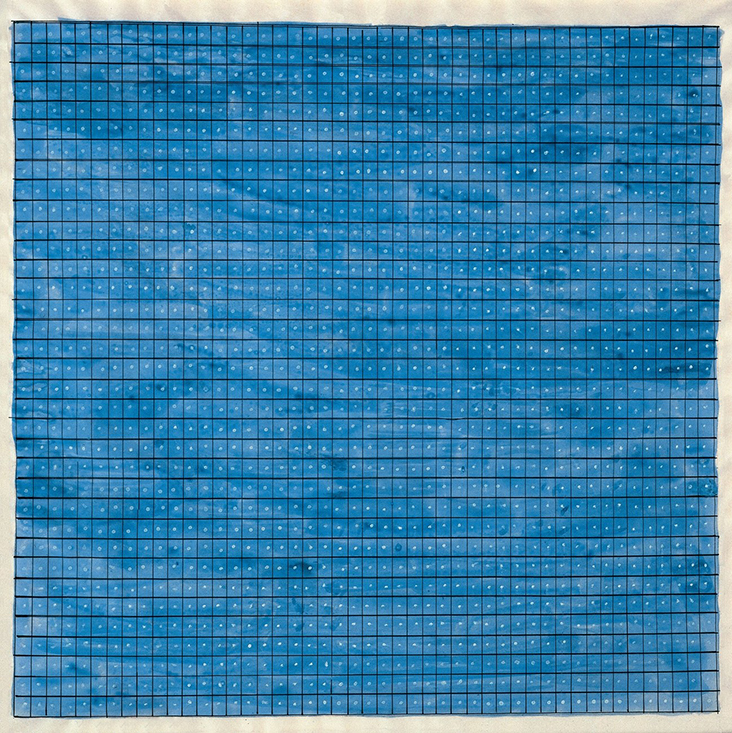

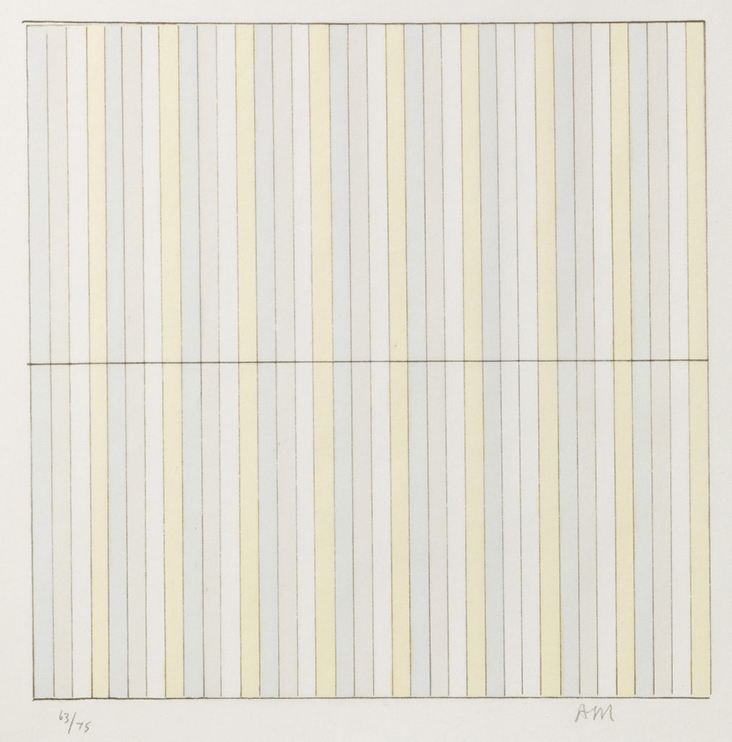

In the cavernous former sailmaker’s loft Martin rented at Coenties Slip, though shabby, rundown and freezing, with no water or central heating, it spelled a unique kind of freedom for Martin as she began producing her first Minimalist grids here, tight networks of trembling lines threaded with subtle colour modulations or even strands of gold leaf, lending them a quasi-religious property. In distinction with the more blatant Minimalism of her contemporaries Martin’s work was loaded with quiet sensitivity, a quality which could invoke a spiritual, sublime experience for the viewer. In The Islands, 1961, Friendship, 1963 and The Tree, 1964, tightly woven hand drawn pencil grids spread over muted, painterly backgrounds, merging precise mark making with the warmth of human touch; she was an exacting perfectionist, destroying any work that didn’t measure up. When her work was included in landmark exhibitions including Solomon R. Guggenheim’s Systematic Paintings, 1966 and Virgina Dwan’s 10, 1967, alongside the mostly male band of Minimalist leaders including Carl Andre, Jo Baer, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt, Martin’s place in art history as a leading Minimalist was confirmed. In 1967 a retrospective was staged at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, featuring her Minimalist grid work from the last 10 years.

Though there were patches of security and happiness during this time as Martin found her voice as an artist, her personal life became increasingly troubled as she was plagued by growing mental health issues. After suffering from auditory hallucinations and bouts of catatonia she was hospitalised on several occasions and eventually diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic. Suffering from such issues made her a somewhat solitary figure, but she found solace in the realms of Taoism and Zen Buddhism, which influenced both her personal and professional life. She was particularly fascinated with the prospect of art as the visual representation of a mystical, otherworldly realm, which became a salve for, and an escape from her mental health struggles, as she wrote, “Nature is like parting a curtain, you go into it. I want to draw a certain response like this … that quality of response from people when they leave themselves behind, often experienced in nature, an experience of simple joy… My paintings are about merging, about formlessness … A world without objects, without interruption.” Even so, there is an unnerving, disquieting sense of unease that quivers beneath much of her art, as writer Charlie Lee-Potter points out, “traces of torment are always present.”

Legend has it, in 1967 Martin dramatically ditched her life in New York, bought a pickup truck and disappeared into the New Mexico desert. The move may have been prompted by an increasing dissatisfaction with her life in New York, as she later commented, “I left New York because every day I suddenly felt I wanted to die and it was connected with painting. It took me several years to find out that the cause was an overdeveloped sense of responsibility.” For the first year of her disappearance, she was a complete ghost, though some accounts suggest she visited India and the Western United States, eventually resurfacing at a gas station in Cuba, New Mexico in 1968 in search of some land to rent. Settling in a barren area of wasteland 20 miles from the nearest highway, with no electricity, phone line or neighbours, Martin constructed a hut for herself from adobe bricks and built a log cabin with trees chopped down from a nearby forest. Much like Georgia O’Keeffe and Mark Rothko before her, in this land of wilderness and isolation, Martin found a sense of spiritual liberation, free from the trappings of urbanised materialism, where she could grow and harvest her own vegetables and live a modest, simplified life.

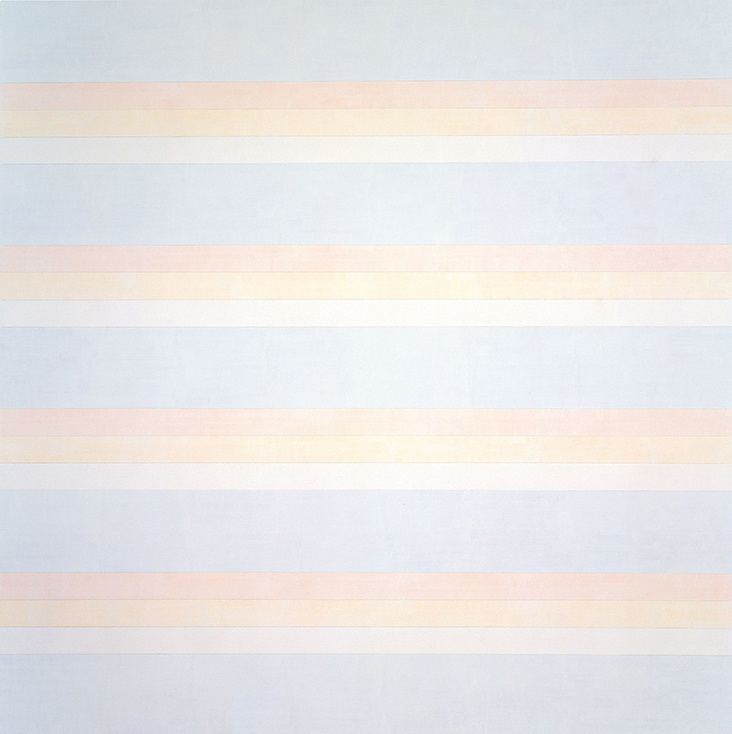

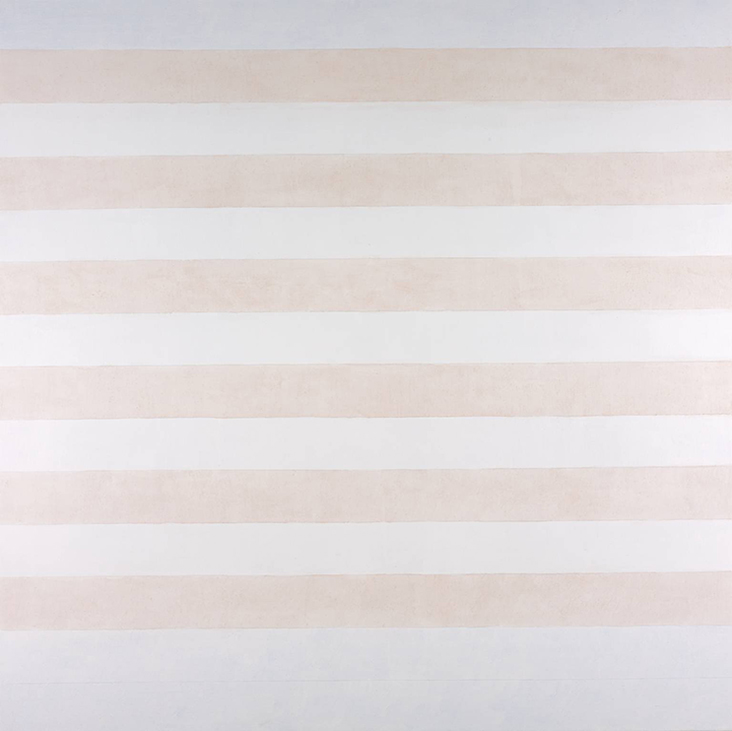

For seven years Martin stopped making art, but found a creative outlet through writing poetry and prose, with a spare, minimal language that echoed the style of her art, forming abstract reflections on the meaning of life, such as “Beauty is the mystery of life. It is not just in the eye. It is in the mind. It is our positive response to life.” Slowly Martin began to make art again, as her ascetic lifestyle infused into a new, more pared down style, appearing first in prints, then drawings and eventually as paintings again, which featured watery stripes of pastel colour and trembling pencil lines drawing in horizontal bands across wide open, huge panels. The isolation had revived her, where she says she found, “A world without objects, without interruption … or obstacle,” to “…accept the necessity of the simple direct going into a field of vision as you would cross an empty beach to look at the ocean.” By 1974, Martin was ready to show her new work to the world, inviting her dealer Arne Glimcher to come and visit her in New Mexico, sending him a hand drawn map with directions.

Glimcher continued to promote Martin’s new work in his Pace Gallery, while her reputation grew exponentially following this spell of reinvention. Martin’s apparent isolation set her apart from the pack and gave her a cult status as a form of desert mystic, attracting swathes of artists who would make pilgrimages to seek her out. Though she has been portrayed in the media as an isolated hermit, more recent accounts of her life reveal her role as a generous philanthropist who was involved with the local communities around her, in Cuba and later Galisteo, where she donated funds for improving local facilities, while giving generously to charities for supporting disadvantaged youths and victims of violence.

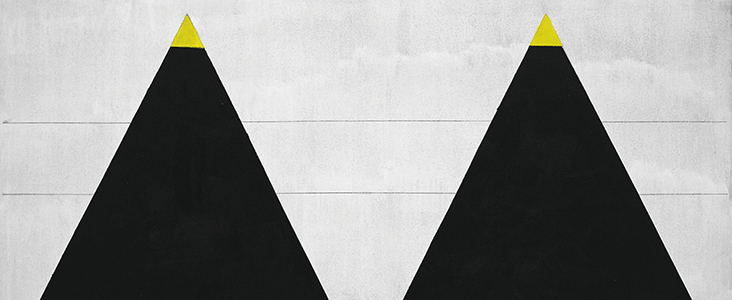

In her later years Martin also gave a series of public lectures reflecting on the meaning of life and art, gaining her an even wider pool of followers. She moved into a less remote retirement community in Taos with a nearby studio, and began including a broader range of shapes in her art, including triangles, trapezoids and squares, while continuing to explore a meticulous language of order and restraint, as seen in Untitled #2, 1992. In 1994 the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos began work on a dedicated wing for Martin’s practice, a site now known today as the Agnes Martin Gallery. Martin died in 2004; she had hoped to be buried in the garden of Harwood Museum in Taos but was forbidden access; maintaining her reputation as the rebellious outsider, a group of Martin’s friends sneaked in and scattered her ashes under an apricot tree on site.

Much like her art, Martin’s life was private and enigmatic, loaded with mystery and intrigue. An endless stream of artists have followed in her footsteps, continuing her spare, delicate language that speaks of mystical spirituality and sublime beauty, including Eva Hesse, Ellen Gallagher, Vija Celmins and Julie Mehretu. Her much loved gallery in Taos has been likened to Matisse’s Chapel in Nice and Rothko’s Chapel in Houston, comparisons which reflect her overarching, lifelong desire to create art as an escape from the chaos of urban life, lifting us out of the ordinary and into the realms of the great beyond.

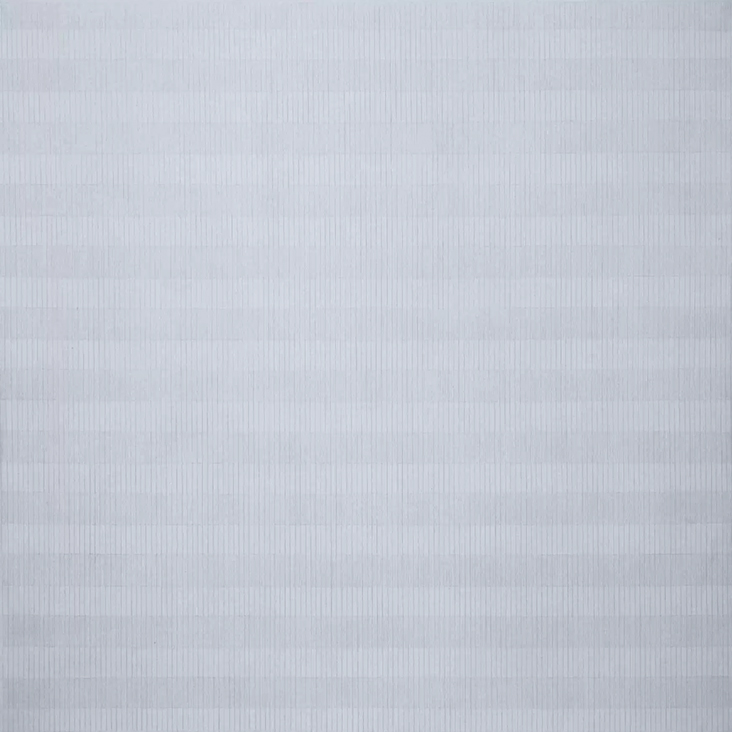

Feature Image: Untitled #1 (Detail) / Agnes Martin / 2003

5 Comments

Mary Chapitis

I think the work shown in this article is more design than art, suited for textiles. I find some of her other work to be much more interesting.

Emily Ulrich

I have always had a heart for Agnes Martin. I just saw one of her paintings at Crystal Bridges in Bentonville, Arkansas. Her work brings a sense of calm and peace. Thank you once again for your insightful bios.

Marian Spadone

I had the opportunity to see many of her works a few years ago when I lived in Taos. Thank you for this wonderfully enriching article. It helps me to see more deeply into what she was doing and what she might have been working toward. It makes such a difference to have a bit of surrounding information when looking at an artist’s work. I’ve recently finished a 3 week silent retreat and as a result of that and your well written article I am appreciating Agnes Martin and her works even more.

Maureen Christensen

Beautiful article Rosie and what a fascinating woman to read about

Susan Johnson

Thank you. as always, your writing inspires me. Agnes Martin being a soul favorite.