FS Colour Series: Froth inspired by Edouard Manet’s Luminous Blushes

FROTH linen’s pale blush tone is reminiscent of an apricot ripening in the white spring sunlight, recalling the luminous flesh tones in French master Edouard Manet’s paintings. As a Realist painter, Manet made the human figure his central focus, whose pale blush tones become visions of purity and light when set against deep, earthy browns and velvety blacks. On constructing his own distinctive, high contrast paintings Manet wrote, “… look for the main light and the main shadow; the rest will come naturally.”

Born to a wealthy family, it was hoped the young Manet would study law, but from early on he had his sights set on a career as an artist. While studying art under Thomas Couture in Paris, Manet travelled widely through Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, absorbing influences from various painters along the way. The dramatic lighting and brooding scenes from Dutch painter Frans Hals and Spanish artists Diego Velasquez and Francisco Jose de Goya made their way gradually into Manet’s own paintings, allowing him to find his signature style.

When Manet opened his own Paris studio in 1856 he found the freedom to develop his artistic voice, combining loose, painterly brushmarks with stark tonal contrasts, illustrating what he called a “mania for seeing in blocks.” In the 1860s Manet developed a penchant for Spanish culture; when a Spanish ballet troupe visited Paris in 1862 Manet persuaded Lola de Valence to pose for him, panting her emerging from the darkness with gleaming ivory skin and jet black hair, wearing a bouquet of rich floral pattern. Writer Charles Baudelaire championed his friend’s painting, writing, “…in Lola de Valence see scintillate/surprise! A charming jewel of black and pink.”

In Dejeuner sur L’Herbe, 1862-63, painted the same year, Manet’s female models are stripped bare amidst a dark, lush woodland, joined by two male figures clothed in black. The female figure in the foreground draws us in with a direct stare, while the luminosity of her pale, ivory skin takes centre stage, made to glow like a beacon of light surrounded by the blacks, browns and greens of the undergrowth, a symbol of youth and purity in such a scandalous scene.

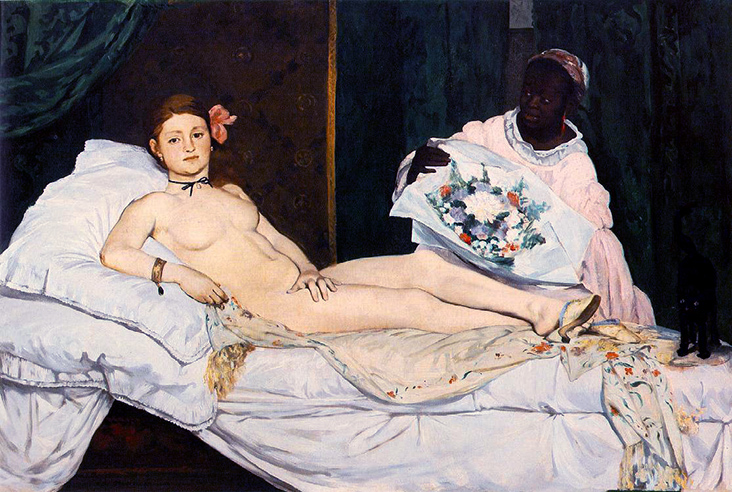

The following year Manet painted the controversial nude study Olympia, 1863, transforming Titian’s Renaissance masterpiece Venus of Urbino, 1534 into a Modernist symphony of near monochrome hues. The pale ivory of Olympia’s delicate skin nestles amongst a complex melange of rippling white and cream bedding that twists, creases and folds like meringue, radiating light from a stark backdrop of chocolate brown, burnt gold and forest green.

In the following years Manet moved away from nude figures towards depictions of everyday 19th century life as observed on the streets of Paris, including café, bar and restaurant scenes. In The Railway, 1873, a woman and child waiting on a street corner are painted with peachy skin that looks rich and creamy against both dark – in the black railings and navy clothing – and light – in white billows of steam and the girl’s chiffon dress.

By contrast, Le Printemps, 1881, is a celebration of spring, blending together blush skin untouched by the sun with fresh, zingy pastel tones of mint green, pale mustard yellow, nude and coral pink, offset with only a strand of black fabric tying the model’s hat on. Manet continued his affinity with nude flesh tones in the following years, making paintings including Chez le Pere Lathuille, 1879, in which light peach colours bleed outwards from the models’ skin into the man’s clothing and the sandy ground beneath them. Here blush tones are complemented with streaks of ginger and sienna brown, suggesting the warm light of a Parisian summer afternoon, cut through with cold, acid sharp greens in the background.

Just one year before his death Manet painted the lonely barmaid in A Bar at the Folies Bergere, 1882 with the pale ivory sheen of her fair skin on chest and arms bringing light into the scene, contrasting with the matt navy velvet of her dress and glossy oranges and bottles in the foreground. In the mirror behind her, darker flesh tones colour two vertical pillars, complementing her flushed face, while soft blues blend into a blurred, distant crowd of unknown people seen only as flickering patches of nude, peach and brown, capturing a fleeting moment in time as it begins to disappear.

FS FROTH comes in Medium weight 100% Linen

4 Comments

Patricia Pfeiffer

Lorraine, I think this was to compare a beautiful new color of linen to a master of fine art’s use of similar color. The skin tones of non Caucasian people has a beauty of its own. I don’t think it was meant to slight anyone of a different color, and was meant to point out the beauty of the froth color of that particular linen. Let’s hope that when and if they produce some darker colors of their linen fabrics we will be treated to a similar display of the fine arts featuring the beauty of non Caucasian subjects. In the meantime, in the artwork shown note the contrast of light and dark, and imagine how beautifully this froth color would play up the beauty of darker skin tones. Probably a better look than it would be with pale skin.

Eva Hudkins

Thanks for the lovely enriching article(s)! There are few occasions to see and learn about art and artists in the daily life of even a small college town. And gorgeous linen to match, brilliant.

Lorraine Williams

Not everyone who got this in the news letter has a Caucasian complexion. This article, while pretending to be a study on Manet, simply lauds pale skin tones. What are you trying to tell the rest of us?

Nancy Stockman

that in this day of only dark/tanned skin is beautiful pale can be beautiful also!!