Arts and Crafts: The Medievalists

Throughout the Arts and Crafts era a momentous revival of medieval ideas and aesthetics took place, leading to a whole new strand of art and design whose influence continues to be felt today. Led by the writer John Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelite painters, who championed the social structures and technical skills of medieval artists, the rustic charm and quiet symbolism of medieval art spread into interiors, fabrics, furniture, stained glass and architecture during the late 19th and early 20th century, reinventing the past for a new era.

Artists, designers, writers and theorists throughout the 18th and 19th centuries were increasingly disenchanted with the ‘shoddy’, depersonalised wares of mass production and the stylised, detached art of the neoclassical era, looking back to the past for a simpler time when more ‘honest’ means of expression existed. In early Christian art’s narrative iconography, natural motifs, jewel-like colours, mosaic patterns and religious symbolism they found a deeper connection to the raw, unadulterated human spirit, allowing these ideas to unfurl in various strands of creative production. Manufacturing methods were stripped back to basics, echoing medieval workshop spaces and guilds – in celebrating the artistry of skilled craftsmanship they raised the status of design to its rightful place on a level with the fine arts, the way it was in medieval times.

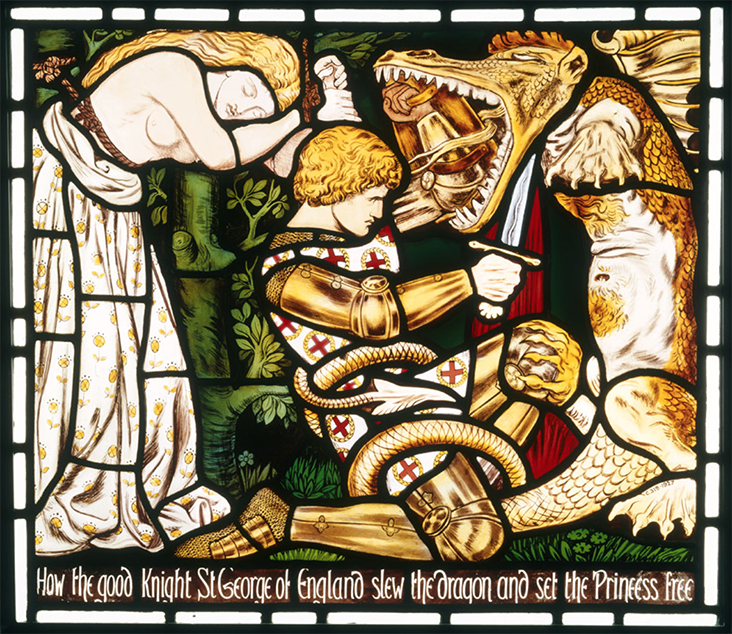

After falling out of fashion for nearly two centuries, stained glass rose from the ashes during the Arts and Crafts era to become a widespread and mainstream form of decorative art. Its symbolic, religious associations and potential to create naturally lit colour made it an ideal form of expression for the new age. While Biblical subject matter was still popular, new ‘glass artists’ were careful not to simply paraphrase the art of the past. Many artists made their scenes more romanticised or idealised, giving them a nostalgic appearance as if viewing the past through rose tinted glasses. In William Morris’ design firm, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co., Morris and his colleagues took on private commissions to produce decorated windows for a range of clients in religious, vernacular and domestic settings. Morris collaborated with Pre-Raphaelite artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ford Maddox Brown and Edward Burne-Jones and together they designed several major commissions including a series of windows illustrating The Legend of St George for Harden Hall in Bingley, West Yorkshire in 1862.

Lady of the Lake, Merlin and Margawse with the Infant Mordred / Veronica Whall and Whall & Whall Ltd / 1933 / Tintagel, Cornwall

As stained glass gained momentum, designer Christopher Whall became a hugely influential figure. He introduced ‘slab glass’, a raw material with crude irregularity and heavy colouring that resembled early medieval glass, giving his contemporary designs a rich, historical weight, while continuing to design panels based on idealised Biblical and mythological narrative subjects. Whall’s daughter Veronica Whall later followed in the family tradition, and together with her father they founded the glass firm Whall & Whall, producing major commissions for cathedrals in Carlisle and Leicester.

Another popular technique lifted from medieval times was embroidery, elevated during the 19th and 20th century from a humble, domestic position to the status of fine art, with many examples now in major galleries around the world. While William Morris experimented with medieval embroidery designs and techniques, it was his youngest daughter, May Morris, who became a leading figure in the field. As a young artist she led the embroidery department at her father’s company, Morris & Co., before leaving to establish her own practice. She produced a wide array of wall hangings, altar cloths and tapestries featuring stylised natural motifs, flowing patterns and elements of gilded thread as influenced by medieval examples, elevating the technique into a veritable art form in its own right, as seen in the free hanging The Orchard, 1890.

Scottish artist Phoebe Anna Traquair shared a similar enthusiasm for the richly gilded, intricate designs of medieval tapestry. In her hugely ambitious series of life-sized embroidered panels The Progress of a Soul, 1895-1902, which took her over seven years to complete, Traquair combines medieval embroidery techniques and styles with contemporary, secular subject matter, illustrating scenes based around the life of the character Denys L’Auxerrois, taken from popular English Victorian writer and critic Walter Pater’s text Imaginary Portraits, published in 1887.

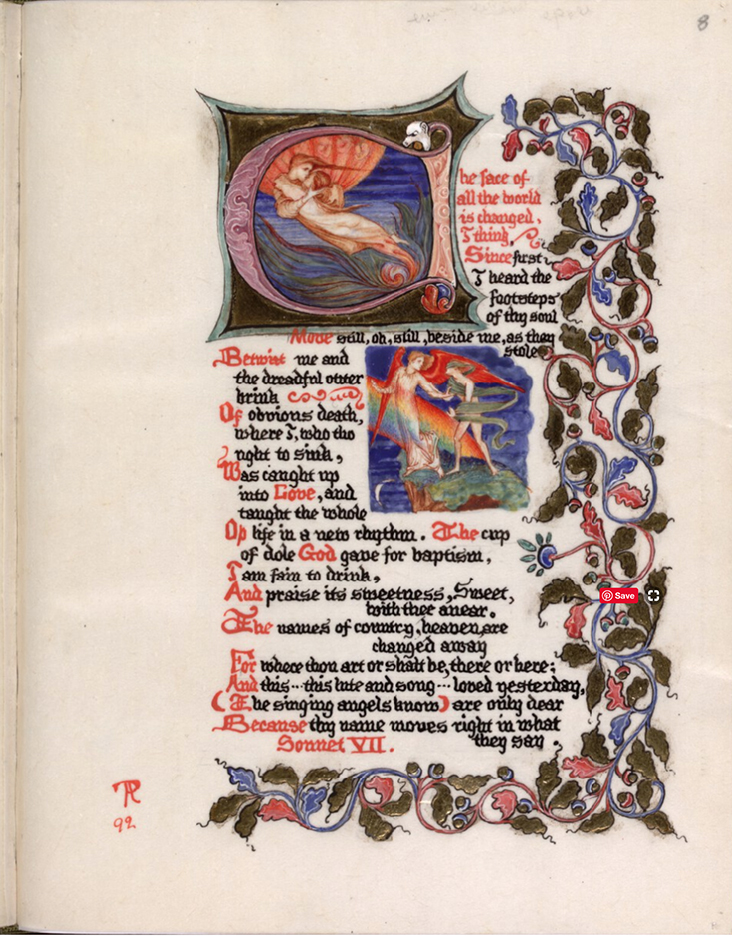

Traquair’s fascination with reviving medieval art and techniques extended into various other media, including illuminated texts which combined elements of graphic border decoration with lettering in deep, rich colours including blue, red and gold. In the late 1880s she wrote to Ruskin, asking to borrow several of his 13th and 14th century Biblical manuscripts, which he agreed to send to her in exchange for some of her original artworks. Initially Traquair made her own illustrations of Biblical subjects, such as The Psalms of David, 1884-1881, before moving on to illustrate contemporary poetry by her peers, including Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portugese, 1850, a series of hugely popular poems about love and romance. Both Morris and Burne-Jones were amongst others who experimented with the illuminated text format as a means of illustrating both historical and contemporary texts, bringing them to life in a new way.

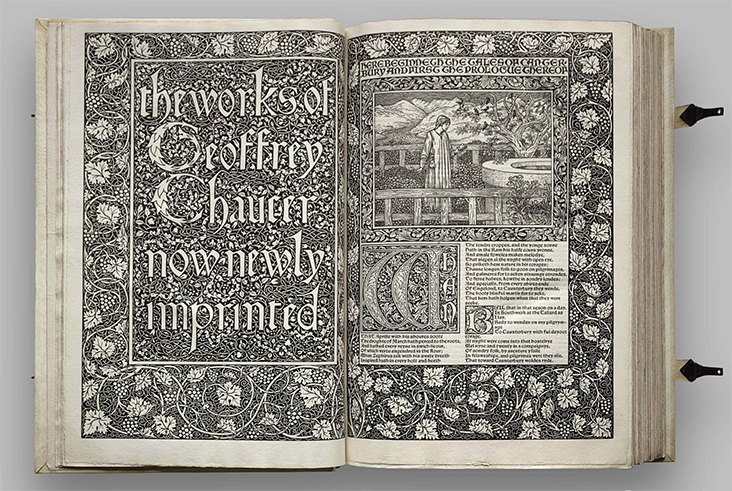

In 1891 Morris extended these ideas further, establishing the much celebrated and hugely successful Kelmscott Press, a small company for producing hand printed books with the tactile qualities from the 15th century, exploring steel paper punches made by skilled craftsmen to print text and imagery. One of Kelmscott Press’ most famous publications was The Works of Jeffrey Chaucer, 1896, featuring intricate, lavishly detailed illustrations by Burne-Jones.

In the following centuries abstraction took over as the dominant style trend, leaving behind the romantic and Biblical subject matter celebrated by the Arts and Crafts. Yet the medieval techniques they revived continued to be explored by artists throughout the following century and many persist even today. Artists including John Piper, Henri Matisse and David Hockney have experimented with the deeply spiritual properties of stained glass as art, combining medieval techniques with contemporary forms and colours. Weaving, tapestry and embroidery were popularised in the following decades through artists including the radical Anni Albers, who continued to level the field between fine and decorative arts, while more recently Tracey Emin has integrated elements of hand-stitching with subversive, contemporary content. The integration of medieval patterns with text and illustration helped shape a new generation of writers and illustrators exploring the ‘artist’s book’ as an art form in its own right, as well as influencing the foundation of independent publishing houses including The Hogarth Press, established by Leonard and Virginia Woolf in 1917, which lasted until the mid-20th century.

Leave a comment