Tradition and Rebellion: The History of Tartan

Born and raised in Scotland, I grew up surrounded by tartan, a pattern associated as much with kitsch Scots traditions and nationalist tartanry as punk rebellion and goth subculture. Despite this complicated duality, there’s no denying that tartan is interwoven with the history of Scotland and Scottish identity. Yet it is also a worldwide phenomenon – thousands of family clan tartans are still in existence today, protected by carriers of the family name, many of whom are spread across the globe. Meanwhile, tartan’s association with irreverence and punk, which dawned in the 1970s, rages on, and the print is now being incorporated into international fashion lines.

The earliest examples of tartan have been traced back as far as the 3rd century CE. Heavyweight wool fabric featuring interlocking stripes in contrasting colours was favoured by Highlanders, wild warrior clan societies who populated the north of Scotland, who would produce their own cottage industry textiles according to personal tastes, lifestyle needs, and availability of dyes.

Tartan’s association with rebellion came to the fore during the 18th century Jacobite rising when Charles Edward Stuart – aka ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ – spearheaded an army of tartan wearing renegades into England in an attempt to bring down Protestant King George II, and restore the Scottish Catholic House of Stuart.

Painting, full length portrait of an Officer believed to be of the 81st (Aberdeenshire) Highland Regiment, oil on canvas, artist unknown, c. 1780.

When the Jacobites were defeated for the last time at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, tartan was largely banned for most of the Scottish population, much of which was uprooted or destroyed during the subsequent, devastating Highland clearances. Instead, tartan was adapted for army soldiers due to its robust durability, shifting tartan’s association with clan society to a symbol of the state; the ban wasn’t lifted until 1782.

At the turn of the 19th century, traditional Highland dress went through a period of revival, although many of those imitating the traditional dress of their ancestors were aristocrats and royalty who romanticised and commercialised the notion of clanship without having experienced the same hardships, lending the textile another new, complicated strand to its identity.

It was around this time that tartan began to be mass produced in large quantities. As a means of differentiating patterns from one another, tartans were initially given names of towns and districts, later followed by the family names of the clans who designed them, a move that revealed just how many distinct versions of the fabric were possible. New variants of tartan also continued to be designed throughout this time.

During the 1970s, tartan’s rebellious roots were reinvigorated by youth culture and punk rebellion, spearheaded by the iconic British designer Vivienne Westwood. She famously ripped apart and restyled the Royal Stewart tartan – the personal tartan of the British monarch – incorporating the plaid fabric with rips, safety pins, buckles, leather, sewn on patches and paint, a style that was later adopted by punk bands including the Sex Pistols and The Clash. Westwood’s love affair with tartan led her to incorporate multiple different clashing types of the fabric within a single garment, as well as even designing her own variant, which she called the MacAndreas tartan in 1993, an homage to her husband, Andreas Kronthaler. “They have all got stories, these fabrics,” she said.

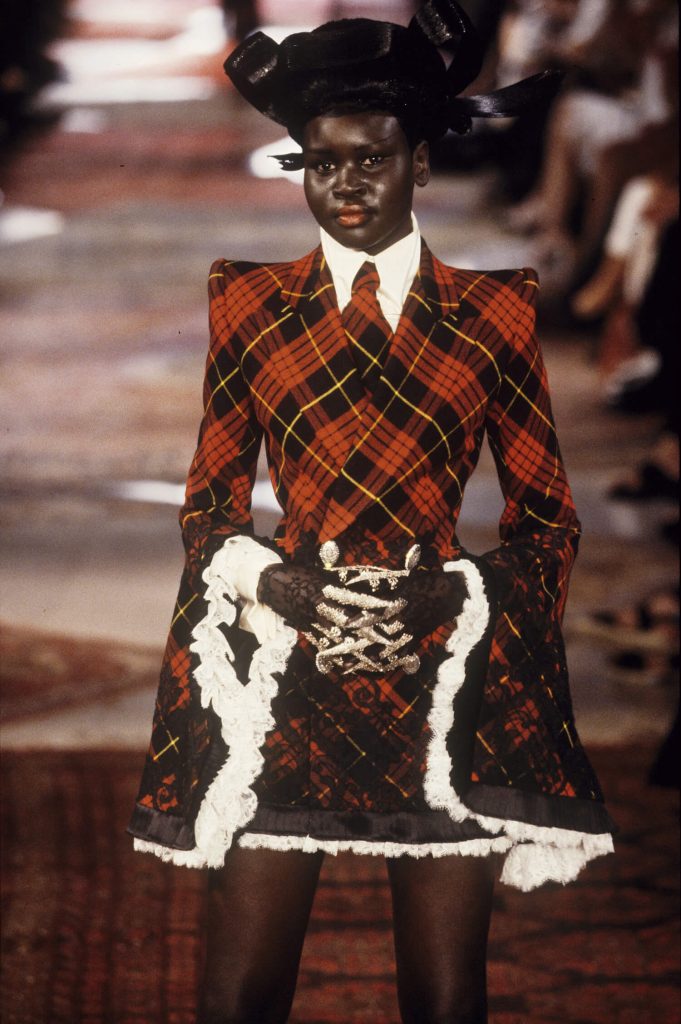

In a similar vein, British designer Alexander McQueen highlighted the politicised nature of plaid fabric, designing his own Clan Macqueen tartan, and basing his collection around the catastrophic impact on Highland societies after the Battle of Culloden, while showcasing how the fabric could be reclaimed anew as a symbol of wild, rockstar rebellion.

Since then, tartan’s identity has continued to evolve in the international sphere, whether incorporated with patterns from other cultural traditions, woven into leather garments or ripped apart and reconfigured a la Scottish designer Joey D. There’s no denying that tartan’s complicated history and shifting political status has played a key role in its success today, and it is now widely recognised as one of the most popular and widespread types of fabric in the world.

Leave a comment