Stitching and Subversion: The Erotic Embroidery of Ghada Amer

Egyptian-French artist Ghada Amer has a widely varied practice spanning sculpture, printmaking, video and installation, but she is arguably best known for her alternative embroidered paintings. From a distance, they might look like expressionistic canvases, but peek closer and they are laced with hidden elements of erotica aimed not for the male gaze, but for the emancipated woman, who she encourages to celebrate, and own, her body. Embroidery is a subversive choice for Amer, through which she hopes to speak to women with a visual language that has been traditionally associated with femininity for centuries. She says, “I like the idea of representing women through the medium of thread because it is so identified with femininity.”

Amer was born in Cairo, Egypt in 1963, but she immigrated to France during her childhood years. In 1984, she trained as an artist at Villa Arson in Nice. A pivotal moment occurred during this time, when a misogynistic teacher denied her access to the painting class, arguing they were for male students only. The experience set Amer on a path to break down the expectations set upon female artists by patriarchal society. Over time she discovered the most powerful means of doing so was through the representation of the female body as symbol of power.

Another key impact on Amer’s attitude towards breaking tradition came through the discovery of the conservative Egyptian magazine Venus, which Amer noted was deliberately adding longer hemlines, sleeves, and veils onto western women, to create what Amer has called “Vogue for the veiled woman.” Shortly after finding copies of the magazine during a visit to see family in Egypt, Amer began working with embroidery and collage in her art.

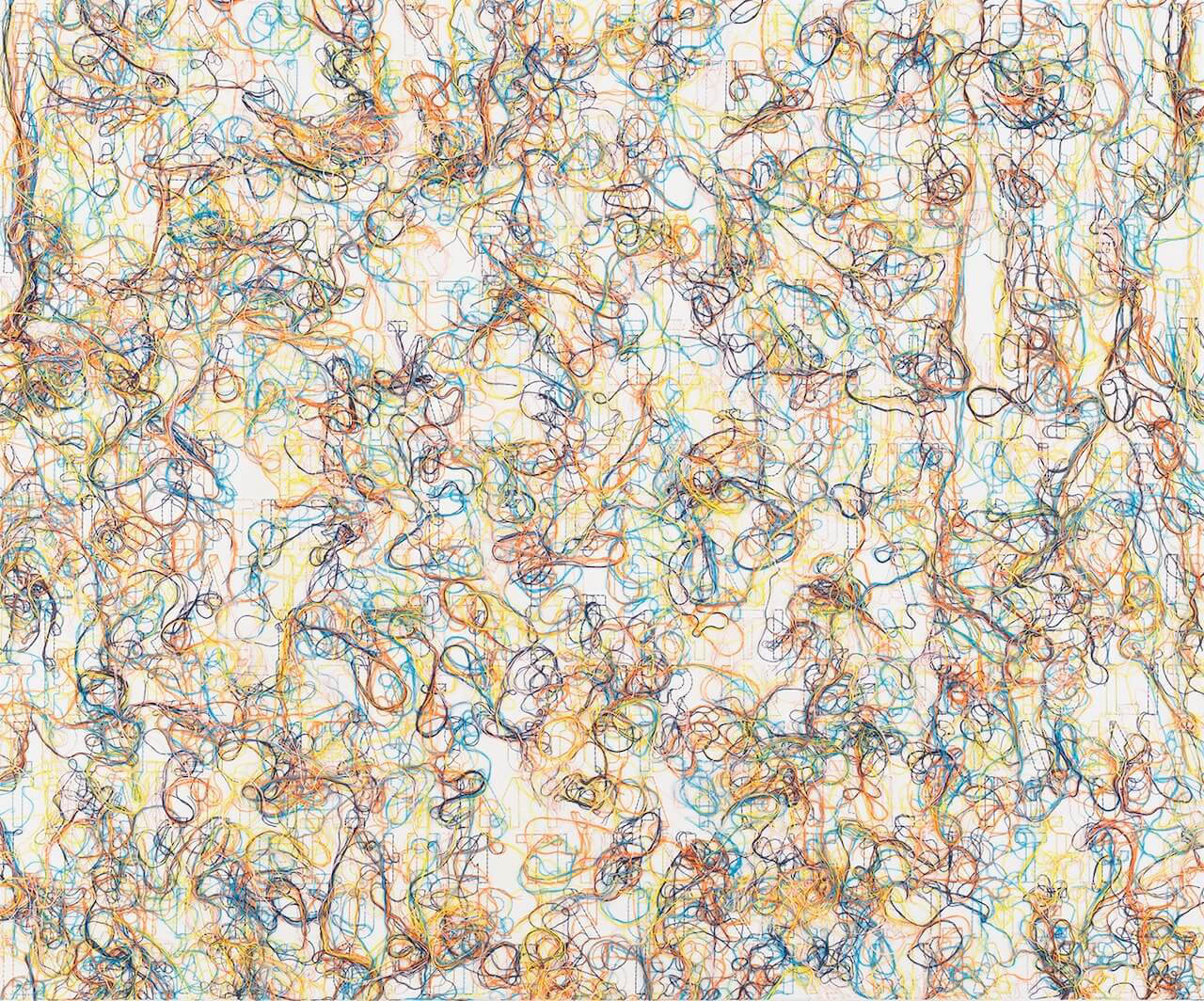

Amer began working with erotic imagery during the early 1990s, tracing images of women from magazines and cartoons before drawing and then stitching the outlines onto canvas. She gathered together the loose strands of embroidery thread and added gel or acrylic medium to give them a paint-like consistency, before arranging them into streaks and swirls that deliberately subvert the macho language of Abstract Expressionism in a medium that is resolutely feminine. After moving to New York in 1996, this strand of her practice became more pronounced, along with visual imagery exploring themes around sexism, terrorism, and acts of oppression.

In part, Amer’s focus on female bodies allowed her to claim what has been a patriarchal tradition – nude females were once seen as fodder to be painted by, and for, the heterosexual male. She is quick to point out how limited women’s choices have been in art, noting, “Historically, women were only allowed to paint portraits of other women, if they were allowed to paint at all.” But Amer also sees depicting nude women as an act of liberation, but for her, and for the women looking at her art. She says, “For me, it helped to overcome these taboos about sexuality that I had acquired from my own growing up. It freed me, the more I looked and drew. It empowered me and I empowered them.” She adds, “I believe that all women should like their bodies and use them as tools of seduction.”

Today Amer describes her art as “a hybrid of the West and the East,” which fuses together influences as varied as French attitudes towards the veil, sections of banned medieval erotic texts from the Arab world, Claude Monet’s water lilies, and the late nudes of Paul Cezanne. All this demonstrates just how rich and multi-layered her practice really is, and how wide-ranging a feminist art practice can be.

One Comment

Pingback:

Powerful Female Artists in the Contemporary African Art Scene - Art Network Africa