FS Colour Series: Barn Red Inspired by Edward Hopper’s Modern Life

The great American realist Edward Hopper had a remarkable gift for observation, finding strange intrigue in the most unlikely of places. Gas stations, late-night bars and quiet buildings tucked away in the wilderness all take on an enigmatic wonder through his stark, directional lighting, angular compositions and striking accents of colour. BARN RED Linen’s entrancing shade of red was a colour he would explore throughout his career, considering how this bold, seductive hue could bring enticing streaks of juicy colour into otherwise muted, pared back scenes and injecting them with the spirit of modernity.

Hopper was born in Nyack, New York in 1882 to a middle-class family who supported his early inclinations towards art. He began his artistic training as an illustrator at the Correspondence School of Illustrating in New York City, but stayed for only a year before enrolling in painting classes at the New York School of Art. Hopper studied under the American Impressionist William Merritt Chase and the artist Robert Henri – both encouraged Hopper to paint the real world around him in a direct and honest manner. After graduating, Hopper travelled throughout Europe, visiting Paris and Spain where he encountered European avant-garde styles of art including Fauvism and Expressionism. But it was the Impressionist painting of Edgar Degas and Edouard Manet that really piqued his interest, particularly the way both painters made astute, yet emotionally resonant observations of ordinary life.

In the 1910s Hopper settled in the Greenwich Village area of New York and gradually carved out a niche for himself as a painter and printmaker, but success came to him slowly; he didn’t have his first one-man show until 1920, when he was 37. Hopper increasingly spent his summers in New England from this period onwards, where the distinctive raking light began infiltrating his painting style.

The later 1920s were a defining period in Hopper’s career as a series of successful solo shows came his way. It was Hopper’s ability to capture the quiet unease of quotidian life that really captured public attention, particularly young women alone in bars and restaurants as they experienced new levels of freedom. Chop Suey, 1929, one of his most iconic works of art, documents one of the many Cantonese restaurants that were popping up on the expanding streets of New York and beyond. There is no food on the table; instead, Hopper focusses on the atmosphere of the place as streaks of white light form a theatrical spotlight in the centre table, where a young woman gazes blankly into the distance past her female companion. Beyond her, the red shop sign is a glaring beacon of electricity, a potent symbol of industrialised modernity.

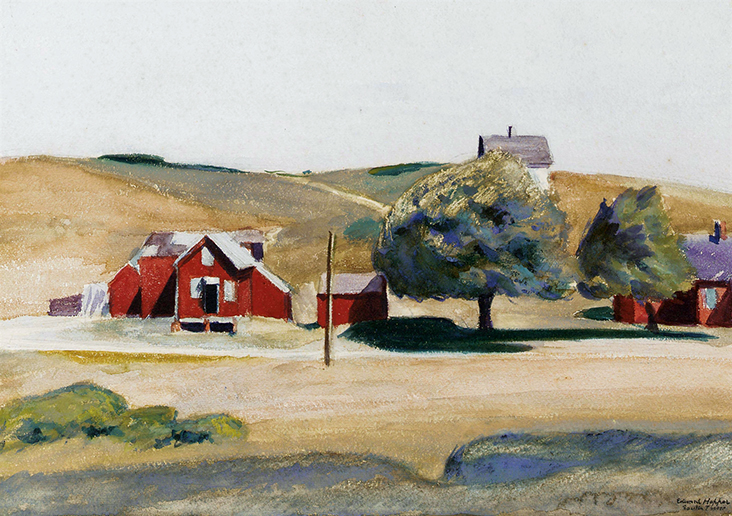

In 1930 Hopper began spending summers with his wife Josephine in Cape Cod. This shift in location marked a new departure in Hopper’s art as he began painting the red barns scattered across the barren hillsides of Truro with geometric panels of intense, electrifyingly bright red. South Truro Post Office, 1930 was made during Hopper’s first summer visit to Truro and it captures the small red buildings nestled tightly into the surrounding landscape, a stark symbol of human life in an otherwise unspoilt wilderness, all lit up by the intense, glaring light of the American Northeast.

As his reputation grew Hopper’s paintings became increasingly focussed on marginal people or places that could just as easily be overlooked, conveying the unsettling beauty of these haunting scenes. Gas, 1940 is a desolate gas station surrounded by thick forestry, while the darkening sky curving in the distance suggests the uneasy encroachment of nightfall. But Hopper’s distinctive glossy red lights up the scene, a comforting symbol of civilization in amongst the wilderness.

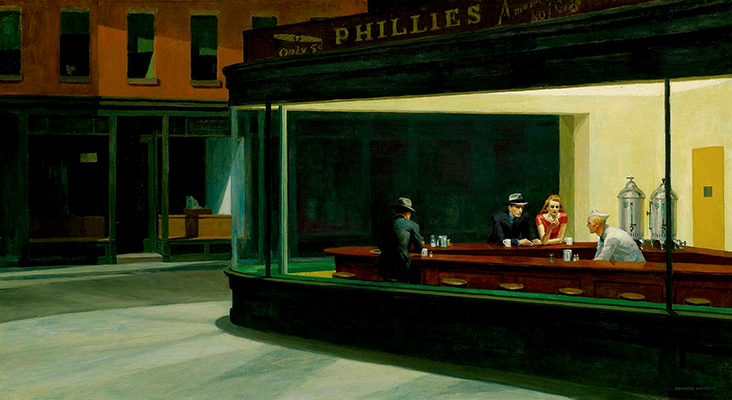

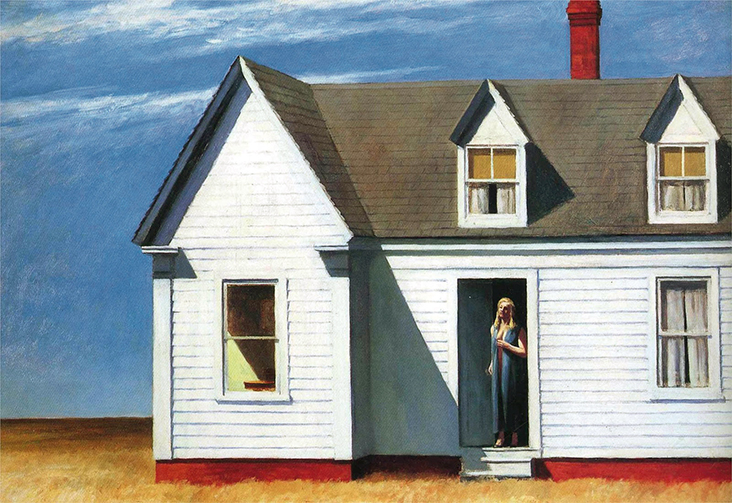

Nighthawks, 1942 is Hopper’s most celebrated painting, a timeless icon of modern life as a lonely New York bar lights up the dead of night. Silent streets are crisp, cold and grey, while fluorescent lighting casts an eerie glow on the three disconnected ‘nighthawks’ inside the bar. The vibrant wine red of the woman’s dress becomes a focal point for the entire scene, placing her at the centre of this mysterious and unknown story. High Noon, 1949 also pivots around a single female, this time lingering in the doorway of a Cape Cod House as the glaring sunlight fills her surroundings. The pristine house is awash with crisp white light, but rich streaks of red stain the base and chimney beyond, injecting just a hint of enticing danger and drama into her peaceful life.

Leave a comment