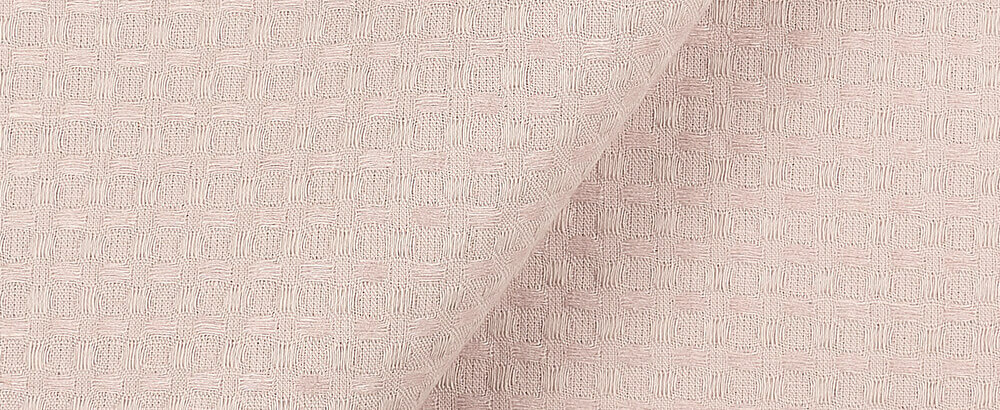

FS Colour Series: Orchid Tint Inspired by Georgia O’Keeffe’s Pale Flowers

Pioneering modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe made a series of radical breakthroughs during the early to mid-20th century, taking seemingly ordinary, everyday subjects and investing them with a newfound wonder. Of all the subjects she painted, it is her flowers that have received the most critical acclaim; fleshy, bold, and daringly direct, they broke away from the frilly, ostentatious flower paintings of the past and proved these stereotypically anodyne motifs could be loaded with power, risk, and innuendo. In many of her flower paintings, O’Keeffe explored how subtle, nuanced shades of rose-tinged lilac, like Orchid Tint, could be coupled with sharp accents of intense colour and black, creating abstract and instantly memorable designs. She said, “I had to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I was looking at – not copy it.”

Georgia O’Keeffe was born in 1887 and grew up on a farm near Sun Prairie Wisconsin. She trained as a painter at the Art Institute of Chicago, followed by the Art Students League in New York, after which time she spent several years teaching in West Texas. The art she made while working as a teacher was to become foundational – surreal charcoal drawings exploring close up, cropped details of organic shapes and forms that veered close to abstraction, suggesting fertile, fleshy forms. On a whim, O’Keeffe mailed these drawings to a friend in New York, who in turn showed them to the renowned photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz. Deeply fascinated, Stieglitz offered O’Keeffe a solo exhibition in his New York gallery, and the pair began a longstanding love affair.

These early drawings paved the way for O’Keeffe’s formative flower paintings in the years that followed as she settled into a life in New York City. She focussed predominantly on large- closely cropped views of flowers, transforming their seemingly humble, domestic qualities into haunting, mesmerizing visions of another world. Many critics interpreted her curvaceous, fleshy flower forms as sexualised, particularly as the innuendo laden school of Surrealism was taking hold across much of Europe and beyond. But O’Keeffe spent decades denying any such suggestions, inviting us instead to see the wonder and mystery she observed in nature as it unfolded before her.

In Black Iris, 1926, O’Keeffe enlarges the inner caverns of an iris to epic proportions, reinventing its fragile, elemental qualities into something far more enduring and monumental. Dark petals in crimson, purple and black lend gravitas and weight to the single iris flower, while airy shades of lilac and white form whispery tones above them, creating a stark, theatrical balance of opposites. Dark Iris no. II, 1927 is even more daring and experimental in design, taking an off-centre view into the flower’s inner, macro details. Soft, pale purple and lilac tones billow with the softness of clouds throughout much of the image, off-set against angry ripples of grey and maroon that introduce elements of danger and menace.

In the visionary Narcissa’s Last Orchid, 1940, we see O’Keeffe’s growing accomplishment in balancing the fragile and intricate, bone-like structures of flowers with larger areas of brooding atmosphere and tone. In this image O’Keeffe couples the stark white of the inner orchid with broad passages of pastel pink to denote its wild outer edges, while earthy brown in the lower left adds dense, dark complexity. In another study of the orchid flower, titled An Orchid, 1941, O’Keeffe toys with a more adventurous colour palette, coupling soft, hazy shades of pale purple with shocking accents of yellow and green in the centre, which allude to the flower’s fertile and unstoppable growth. As with so many of her most successful paintings, O’Keeffe experiments with jarring, unexpected visual elements, encouraging us to entirely reconsider the way we look at, and understand, the natural world.

2 Comments

Lorraine Rovig

First, O’Keeffe’s flowers are beautiful. I am pulled in to the mystery of flowers being shapes, shapes not seein elsewhere in nature. They are not just round, just oval, or a repeated shape from elsewhere in nature. They are their own thing. I think the reviewer got lost in rhetoric. The second most important fact about O’Keefe’s flowers is that the shapes are strong, even when the flower is delicately made. The meaning of art always comes from within ourselves. If the artist rejects the idea that they are full of sexual imagery, then I’m OK with that. Beautiful and strong enough for me.

Vicki Lang

O’Keeffe is one of the first great female artists that is well known for her art. Her personal life was as famous as her art work. A famous free spirit. Love her work.