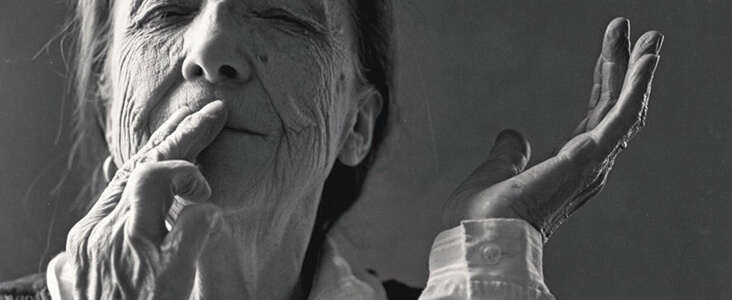

“I Do, I Undo, and I Redo”: Louise Bourgeois and Motherhood

Personal relationships were integral to the pioneering 20th century sculptor Louise Bourgeois, so perhaps it is no surprise that themes of motherhood crept into many of her most famous works of art. Whether addressing her relationship with her own mother, who died when the artist was 21, or her own shifting role as she herself became a mother to three children, her maternal-themed art asked powerful and emotionally stirring questions or addressed uncomfortably graphic home-truths about what it really is to be a woman, and a mother, in the modern world. She said, “I have three frames of reference…my mother and father…my own experience…and the frame of reference of my children. The three are stuck together.”

Throughout her career as an artist, Bourgeois made reference to her own childhood in and around Paris, which was deeply troubled and traumatic. Her father made no attempt to hide his long-standing affair with the family au pair named Sadie Gordon Richmond, and this complicated entanglement created an emotional distance between Bourgeois and her father. Meanwhile, as Bourgeois’ mother contracted the Spanish flu and struggled to recover, Bourgeois became fiercely protective of her. The artist’s mother eventually passed away in 1932, leaving Bourgeois deeply distraught, and even more alienated from her father. The death of Bourgeois’ mother affected Bourgeois so profoundly that she made a complete about-turn, abandoning her degree in mathematics to train as an artist.

Just a few years later, in 1938, Bourgeois fled Paris for New York with her new husband, the American art historian Robert Goldwater. She had three sons with Goldwater over a four-year period, while continuing to try and make art. It was undoubtedly a challenge, as Bourgeois later recalled in an interview, “I’m asked all the time, but I never say, it was a lot of work to get through the day. It was really something to have three children and also try to work. It was a lot of physical work.” Anxiety plagued Bourgeois throughout these years, as she struggled to let go of the demons from her own past. She said, “There I was, a wife and mother, and I was afraid of my family…afraid not to measure up.” Bourgeois later spoke of the healing impact psychotherapy had on her, allowing her to release the traumas of her past in order to move more sinuously into being a nurturing mother. Art, too, was a healing device that gave Bourgeois room to express, or extinguish her innermost fears and desires.

In her later years Bourgeois began making art that reflected back on her years with young children. Some artworks illustrated poignant, autobiographical moments, such as the heartfelt Children in Tub, 1994, from a suite of etched prints titled Autobiographical Series. She says this work was dedicated to the way her sons would physically support one another when she could not, noting, “I could never carry a child, even when they were very little. I had to have ways to hoist them. So here they help each other. They are happy – it is very tender.” In other works, such as Mother and Child, 2001, and Woven Child, 2002, Bourgeois reflects on the physical dependency of childbirth and early motherhood, that foundational period when mother and child are so closely intertwined, they are almost the same being.

Bourgeois dedicated a series of spider sculptures to her own mother, a master weaver who was as nimble and crafty as a spider. One of the most ambitious was the colossal Maman, 1999, originally made for Tate Modern’s vast turbine hall. Bourgeois accompanied this sculpture with three tall steel towers titled “I do, I undo, and I redo,” which was as much a reference to Bourgeois’ mother as the artist’s own intuitive experiences in being a mother. In the later sculpture, The Good Mother, 2003, Bourgeois pays tribute to the nurturing sacrifices a mother makes when raising children, as loose spools of thread run from the mother’s breasts like milk – a metaphor for the emotional security a mother passes on to her offspring through a process of dedication, commitment and self-sacrifice. But Bourgeois also points towards the pressures placed on mothers to fulfil certain ideals placed on them by society. As always, there is a wicked sense of humour running beneath this artwork, and one senses Bourgeois thoroughly enjoyed many of the challenges her life as a daughter, a mother and an artist gave her. She said in her later years, “I have been to hell and back. And let me tell you, it was wonderful.”

3 Comments

Christina Donna

Thank you for this post. I am surprised (probably shouldn’t be) that Rosie Lesso has a platform that is very informed and unusually insightful for women artists. Again, thank you so much and I look forward to the next and the next!

BTW. I use fabrics-store heavy linen white canvas.

It’s a great surface to paint on!

Masha Karpushina

Rosie is an art historian which is why her essays are on the subject, thank you Christina.

Penny Gold

Thanks so much for this moving essay on Louise Bourgeois and the theme of mothering in her work. I very much look forward to your blog posts on particular artists!