Textiles Go Pop: Eduardo Paolozzi’s Fabric

British artist Eduardo Paolozzi might be best remembered as the pioneering godfather of Pop Art, a master of cut-and-paste who mashed mass media imagery with modernist art. But there are other elements of his legacy that can often be overlooked, most notably his ground-breaking work as a textile designer. Much like his art, Paolozzi brought an eclectic, freewheeling approach to textiles, incorporating colourful, playful references from the world of industry and popular culture into his dizzying repeat patterns, which could include anything from bicycle wheels and baked beans to expressionist squiggles. These gritty, larger-than-life fabrics were ideally suited to their time, capturing the rebellious energy of youth culture in post-war society.

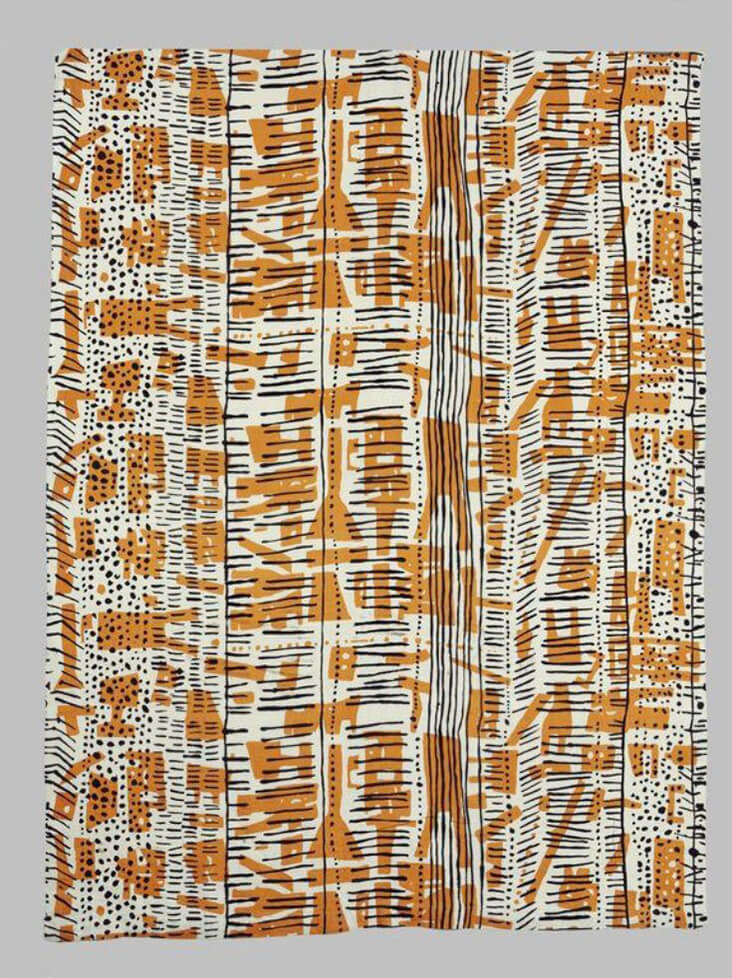

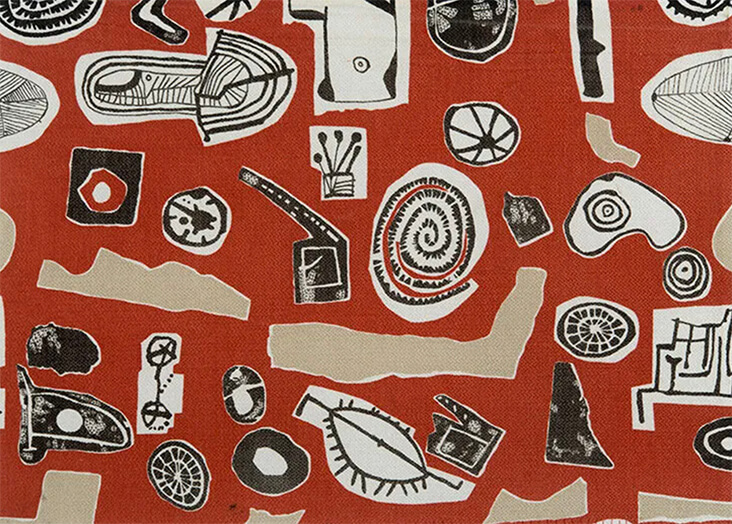

Screen printed cotton twill furnishing fabric, ‘Barkcloth’, designed by Eduardo Paolozzi & Nigel Henderson for Hammer Prints, 1954, V&A Museum, London

Paolozzi was born and raised in Edinburgh, the son of Italian immigrants who ran an ice-cream parlour. The packages, adverts and shop window displays in the ice-cream shop were Paolozzi’s first introduction to visual culture and they consumed his young mind. It was the eclectic mishmash of different references that seemed to fascinate him most, and these would come to inform Paolozzi’s cut-and-paste collage approach to art and design later in life. Paolozzi also enjoyed collecting cigarette packet cards featuring Hollywood starlets or military vehicles, prompting an early fascination with American popular culture.

After training as an artist in Edinburgh, Oxford and London throughout the 1940s, the young Paolozzi remained in London where he hit the ground running, experimenting with a vast range of different disciplines. It was during these early years that Paolozzi established his place as a leading forerunner in Pop Art, creating endless reams of collages, prints and sculptures that played with cut apart imagery from American advertising.

In 1951 Paolozzi married the textile designer Freda Elliot and they moved to a home in Essex – her influence no doubt informed his enduring fascination with fabrics. Throughout the 1950s Paolozzi became a successful freelance textile designer, establishing contracts with leading British companies Horrockses Fashion, Hull Traders, and David Whitehead Ltd. Through these channels Paolozzi was able to produce some of the most progressive textile prints of mid-century modernism. His designs were recognised for their daring and unconventional motifs and patterns that brought jazzy swirls and stripes in tandem with old pipes and bicycle wheels, proving that just about anything could be recycled into a mesmerising repeat pattern. During the 1950s Paolozzi also taught in the textile and print department at the Central School of Art and Design in London, where he would often work late into the night on his own projects.

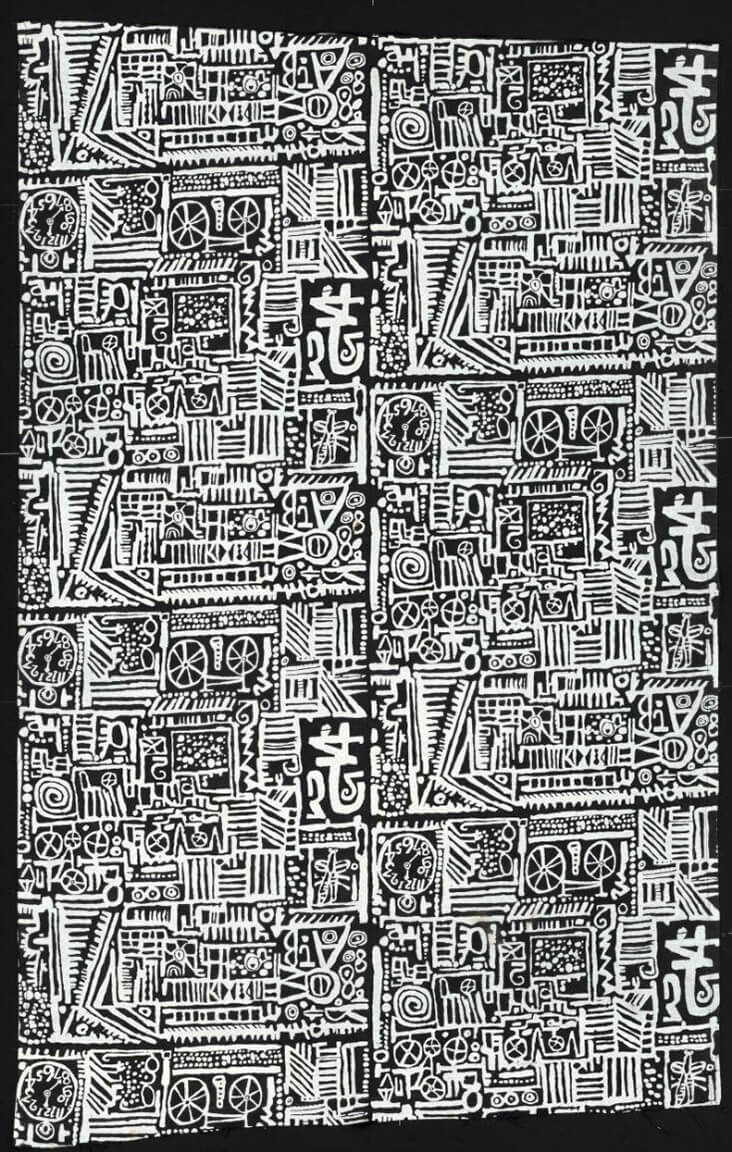

In 1954, Paolozzi established the commercial company Hammer Prints with his neighbour, the fellow artist Nigel Henderson. The company specialised in producing a vast range of fabrics, wallpaper and ceramics with an edgy, subversive appeal. Their idea was to create an antidote to the quaint florals of Arts and Crafts so synonymous with British textiles. Instead, they mined a vast range of visual sources high and low, from Abstract Expressionist squiggles and scrawls to junk shop paraphernalia, children’s book illustrations and marine wildlife. Although they were slow to catch on, and the company closed in 1975, the radical patterns of Hammer Prints have since become recognised as iconic emblems of their time.

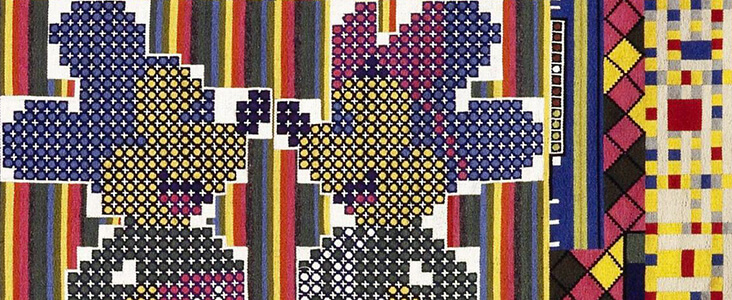

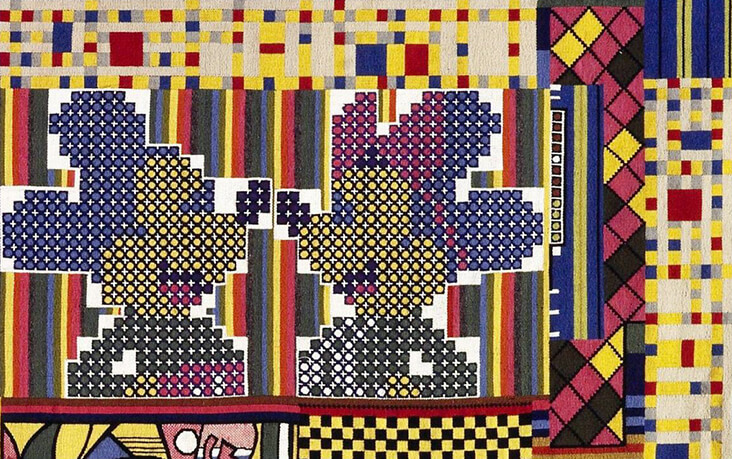

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Paolozzi made several large-scale tapestry commissions based on his works of art. These include the striking Tapestry, 1966, commissioned by the Robert Fraser Gallery, and the richly complex Whitworth Tapestry, 1967. Both reveal the artist’s ongoing fascination with the clash of visual and conceptual ideas, and the arresting impact of geometric patterns. In 1971 Paolozzi was commissioned to produce a series of textiles for Lanvin, which were transformed into elegant clothing, including the famous Djerba Dress, which showcases just how easily Paolozzi’s bold aesthetic could be translated into wearable garments. Although Paolozzi’s later career was focused more predominantly on public art commissions and large-scale sculptures, it is his prolific output from the 1950s to the 1960s that has been the most influential on the next generation of designers since, particularly his restless desire to seamlessly blend one discipline into another. He once put his legacy in the simplest of terms, noting, ” it is sometimes difficult to draw a line between art and craft.”

4 Comments

Vicki Lang

What colorful designs. I love all the bright colors in his designs and the skirt and blouse are gorgeous. the 60’s and 70’s were most colorful of times. I made some bright colored clothes at that time.

Rosie Lesso

Absolutely – thanks for the feedback!

Brenda Osborn

Thank you for this! I knew of Eduardo Paolozzi as a painter and designer of a few tapestries woven at the Dovecot Studio in the 1960s (from doing research for a book about Archie Brennan, tapestry weaver and director of the Dovecot in the late 60s-early 70s). I had no idea this Mickey Mouse design had ever been a printed fabric. I wish I could see it firsthand!

Rosie Lesso

That’s very interesting – do share a link to the book if you would like to! The Dovecot Studios have produced some amazing work…