Fabric in Ukiyo-e Art: Later Developments

In our final article on the role of fabric in Japanese ukiyo-e art, we examine how the genre of ukiyo-e evolved and changed in the 20th and 21st centuries, and the continuing role fabric played in its development throughout this period. Although the dominance of ukiyo-e in Japanese culture largely faded from around 1900 onwards, certain factions of the style remain alive to this day, while its rich legacy has lived on in various modern and contemporary art and design practices throughout Japan, and beyond.

The 20th century was a rapid period of global change, one led by industrialisation and the mass media. This undoubtedly impacted the nature of ukiyo-e, and the people and fabrics that dominated it. Ukiyo-e prints were once a popular form of advertising, but as photography and digital technologies gradually replaced this role, ukiyo-e lost its original populist appeal. This meant ukiyo-e became more widely accepted as a form of fine art to be viewed in gallery spaces and on walls, rather than in books or on billboards. As Japanese woodblock prints infiltrated the west, they influenced the styles of ‘Japonisme’ adopted by Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Edgar Degas and Toulouse Lautrec, and their ideas in turn reinforced the appreciation of ukiyo-e as works of art.

Japanese artist Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (1839-1892) is often referred to as “the last ukiyo-e artist,” yet he is also one of the genre’s greatest pioneers. His career spanned the last years of Edo Japan and the early years of its modern development in the Meiji period, making him an important figure at the threshold of change. He fought hard to retain Japan’s woodblock tradition, injecting new drama, danger and even horror into his prints to reflect the changing times in which he was living. The two-print series’ One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1885–1892), and New Forms of Thirty-Six Ghosts (1889–1892), reveal his fascination with the gothic drama of epic stories, and the role ornate, colourful and stunningly detailed modern Japanese clothing can play in them.

Although ukiyo-e gradually faded from popular Japanese culture after Yoshitoshi’s death in the late 19th century, some factions of the style have remained alive. Fascinatingly, family members descended from the Torii School still sometimes paint billboard posters featuring actors to this day, as their ancestors once did, and ornate costumes made from Japanese fabrics continue to aid in the theatricality of their storytelling.

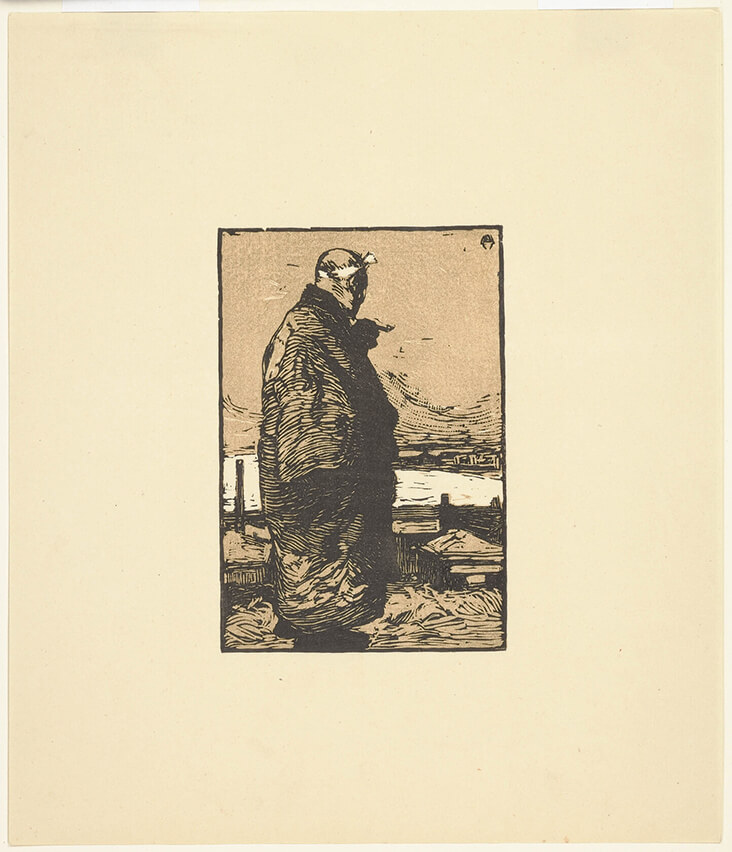

Even if ukiyo-e was fading from view, several early 20th century Japanese art movements took their starting point from ukiyo-e. These include the sosaku-hanga movement, and the shin-hanga style. Sosaku-hanga began in around 1904, and was influenced by several aspects of western art. For one, it emphasised the role of the individual in creating an artwork from start to finish, rather than as part of a team, or ‘school.’ It also introduced elements of western abstraction, expressionism, folk art and naturalism into Japanese art. Still, it kept various aspects of ukiyo-e tradition alive, such as the technique of woodblock printing, and the careful observations of daily life. Kanae Yamamoto was one of the movement’s leading pioneers, and his most striking and celebrated artwork, the woodblock print, Fisherman, 1904, is dominated by a heavy, engulfing robe. Its creases and folds are portrayed with roughly chiselled animated and expressive gouges, making this a modern development on the traditional Japanese woodblock, one that still emphasises the emotional resonance of fabric.

The Shin-hanga movement came a little later, emerging in around 1915. Although its artists focussed on traditional ukiyo-e subjects, they conveyed them in an Impressionistic style, with more realism and expressionism than their predecessors. Hashiguchi Goyo was one of the movement’s greatest pioneers, and his portrayals of beautiful Japanese women in intimate scenarios such as washing or brushing their hair recall the quiet calm of Edgar Degas’ observational art. His prints are dominated by stunningly ornate fabrics, ranging from delicate floral silks to sheer gowns, or soft stripes and checks; in each of his works the fabric aids in building weight of character to his women, much like earlier generations of ukiyo-e artists.

More recently, the Japanese ukiyo-e tradition for flat, bold colours and ornately decorated fabric has been revived by various contemporary artists in Japan. The great, inimitable Takashi Murakami, who has pioneered the ‘superflat’ style and the school of Kaikai Kiki, is undoubtedly bound to Japanese ukiyo-e and its emphasis on the dramatic visual impact of flat colour and black line. He, too, sees the powerful role of fabric in art practice, designing his own printed textiles and elaborate costumes which are integral to his artistic practice. Many artists beyond Japan have also been influenced by ukiyo-e, such as British artist Julian Opie, whose flat shapes and bold, dark outlines owe a debt to Japan’s past. Like Murakami, Opie puts clothing at the centre of his art, styling his models in trendy, cutting edge silhouettes, proving that art, clothing and the ancient traditions of Japan are deeply intertwined.

2 Comments

Madelyn Lenard

I am fascinated by the ukiyo-e school of art. Thank you for introducing it to us. I love the Thread articles and the art history they discuss. Has anyone ever created fabric out of these ukiyo-e designs? I would love to have some if you know whether someone is creating any fabrics out of these designs.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you! I also love all the patterns and colours of the fabrics in Ukiyo-e art. I’m not sure if printed fabric has ever been made out of these designs – let me look into it and I will see if I can find any information!