The Colour of Life: Henri Matisse’s Fabrics

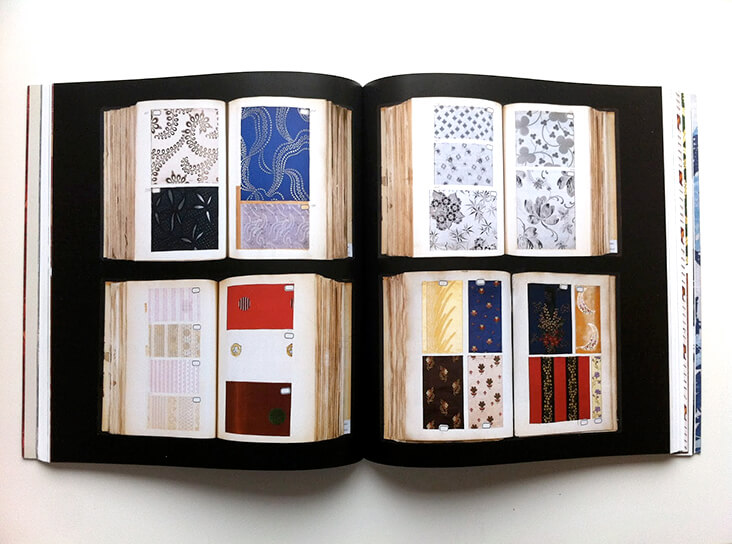

Sample textiles from Matisse’s archive, published in the exhibition catalogue Matisse, His Art and His Textiles, at the Royal Academy, London, 2005

Henri Matisse was an avid, obsessive collector, amassing a huge archive of incredible objects throughout his lifetime that clattered noisily against one another in his home studio. The most cherished of these possessions were Matisse’s impressively vast collection of textiles which he gathered from all over the world, including French tapestries, Persian rugs and African wall-hangings. Matisse found the rich, colourful language of his textile collection so inspiring he called them “my working library,” returning to them again and again to find fuel for his creative fires. “I am made up of everything I have seen,” Matisse reflected in his later years. One of the most fitting tributes to this archive was the iconic exhibition Matisse: The Fabric of Dreams: His Art and His Textiles at The Metropolitan Museum, New York and The Royal Academy, London in 2005.

Matisse was born in 1869 and grew up in the grey, industrialised town of Bohain-en-Vermandois in Picardy, France. In sharp contrast to the area’s sombre scenery, Bohain was much celebrated for its vivid and innovative silks. Matisse’s family had been weaving these silks there for generations, and with no art galleries in the town, these luxury fabrics became Matisse’s first taste of visual culture, lighting up his imagination.

As a young student in Paris, Matisse began his career painting sombre, low-key still life studies in a traditional style, with objects sitting on austere white fabric backdrops. But in 1905 Matisse had a breakthrough that would change the course of his art. While travelling through Paris on a bus, he spied a stunning ‘toile de jouy’ tablecloth featuring blue floral motifs in a junk shop window and rushed to buy it. This simple, cheap fabric of humble origins not only became the starting point for Matisse’s own fabric archive, but also led him to create his most radical early paintings. Works that included patterns inspired by this particular cloth include Still Life with Blue Tablecloth, 1906, Harmony in Red, 1908 and Portrait of Greta Moll, 1908; in all these paintings we see how Matisse envisioned patterned fabric escaping out into the room around it, merging sonorously into the surroundings.

As Matisse gradually found success and financial freedom in the decades that followed, he was able to amass an ever-more adventurous textile collection which in turn dramatically transformed his art. Fabrics came from a huge variety of different sources – in Paris, Matisse visited flea-markets and haute-couture end of season sales to pick up rare and unexpected finds. While travelling throughout Morocco, Tahiti and Algeria, Matisse was dazzled by the intricate and richly complex histories of pattern, seizing as many different samples and reams as his budget would allow, often stretching to the limit of his means.

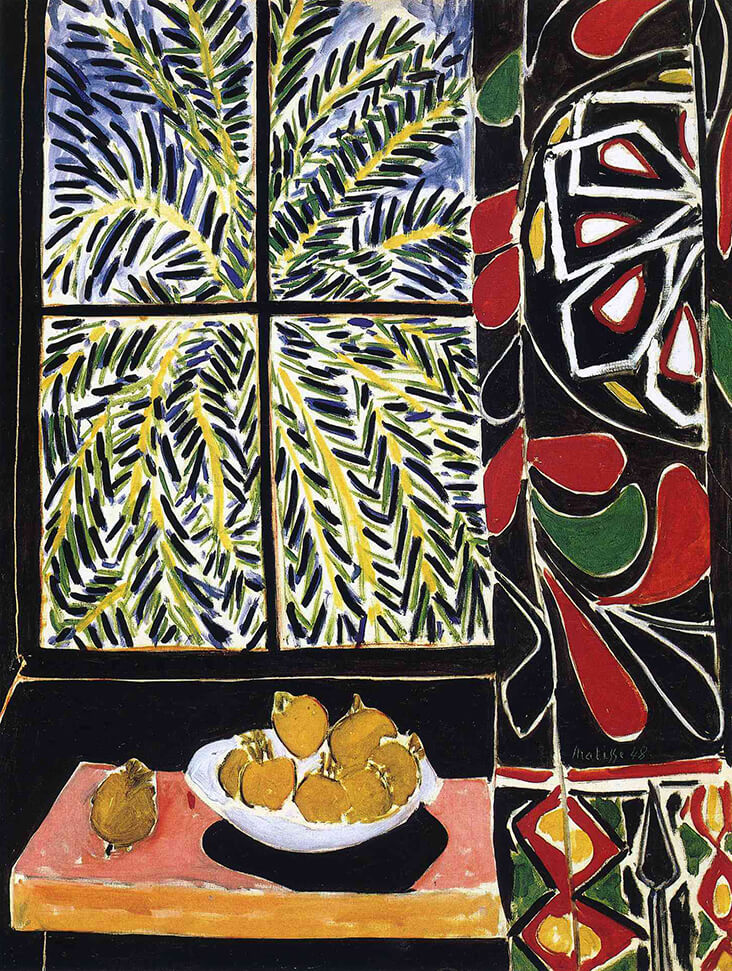

In around 1917 Matisse settled in Nice, where his home became a living, breathing studio filled with his joyously vibrant fabric. Matisse would set up carefully composed theatrical stages featuring clashing colours, prints and patterns and pose female models nestled in amongst them, sometimes adorned in luxurious robes. Works such as Odalisque with Grey Trousers, 1927 and Small Odalisque with Purple Robe, 1937 demonstrate Matisse’s endlessly playful experimentations with pattern and print, which became the primary focus of his art, eclipsing the figures beneath. Other works explored how still life objects could be flattened into one with the patterns around it, such as Interior with Egyptian Curtain, 1948.

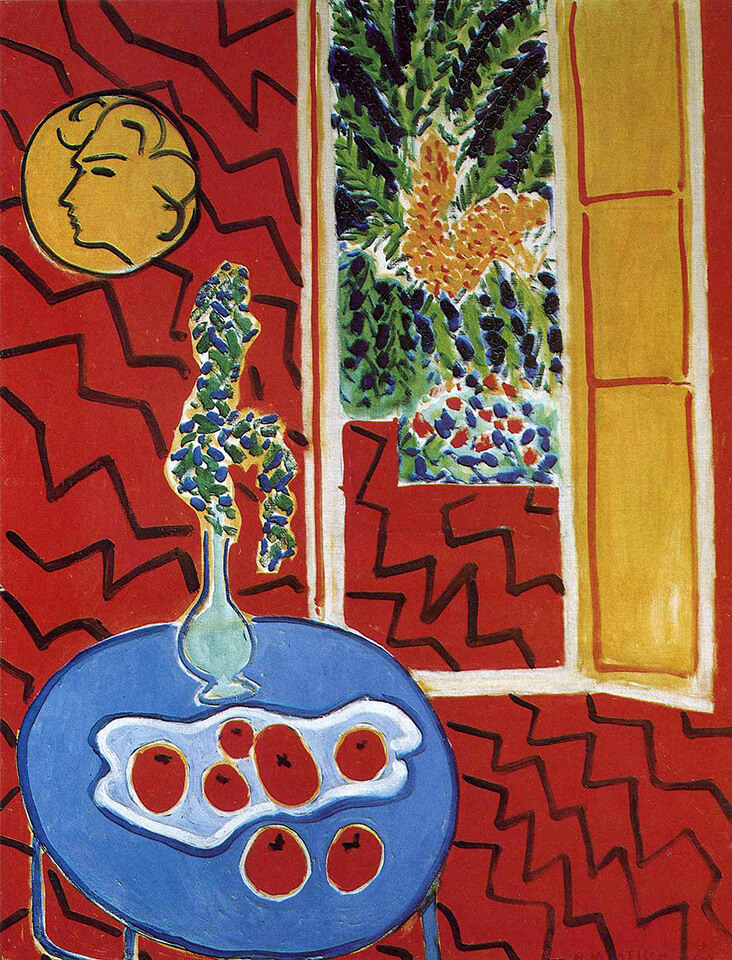

In his later years, Matisse found inspiration in Kuba fabrics from Zaire, with their slim raffia strips, graphic geometric shapes and abstract pattern in rich, dark colours. Matisse said of his Kuba cloth collection, “I never tire of looking at them … and waiting for something to come to me from the mystery of their instinctive geometry.” Many of Matisse’s late artworks echo the angular geometry and flat pattern of Kuba cloths such as the playfully zig-zagged Red Interior Still Life on a Blue Table, 1942 and the designs for the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence. It is also thought the flat panelling of Kuba cloths were one of the primary influences on Matisse’s late paper cuts, the pinnacle of his career, which demonstrate most succinctly Matisse’s enduring, lifelong love-affair with flat, decorative pattern.

3 Comments

Martha F Davis

Totally enjoyed your article on Matisse. One of my favorite artists.

ana Bonifacio

I really enjoyed your writing. Beautiful Matisse

Stephanie Hammer

Thank you so much for your lovely postings about artists. I learn so much from them. Your writing and illustrations are thoughtful and informative in the best way, and always a feast for the mind and eye.