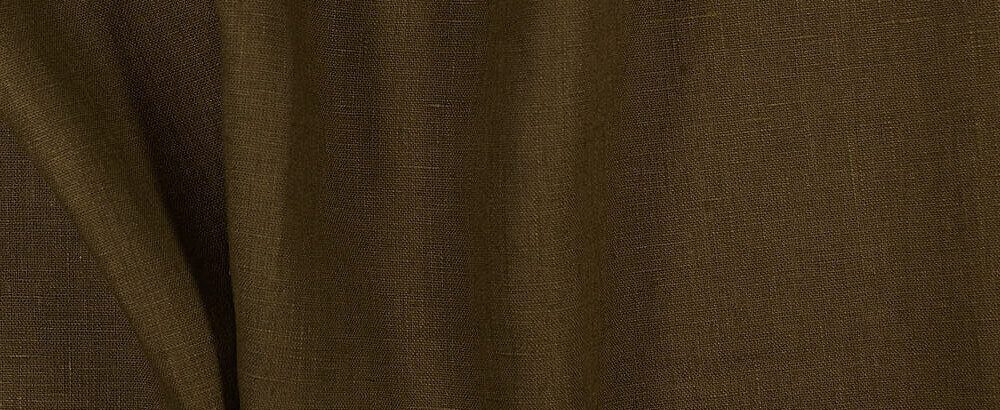

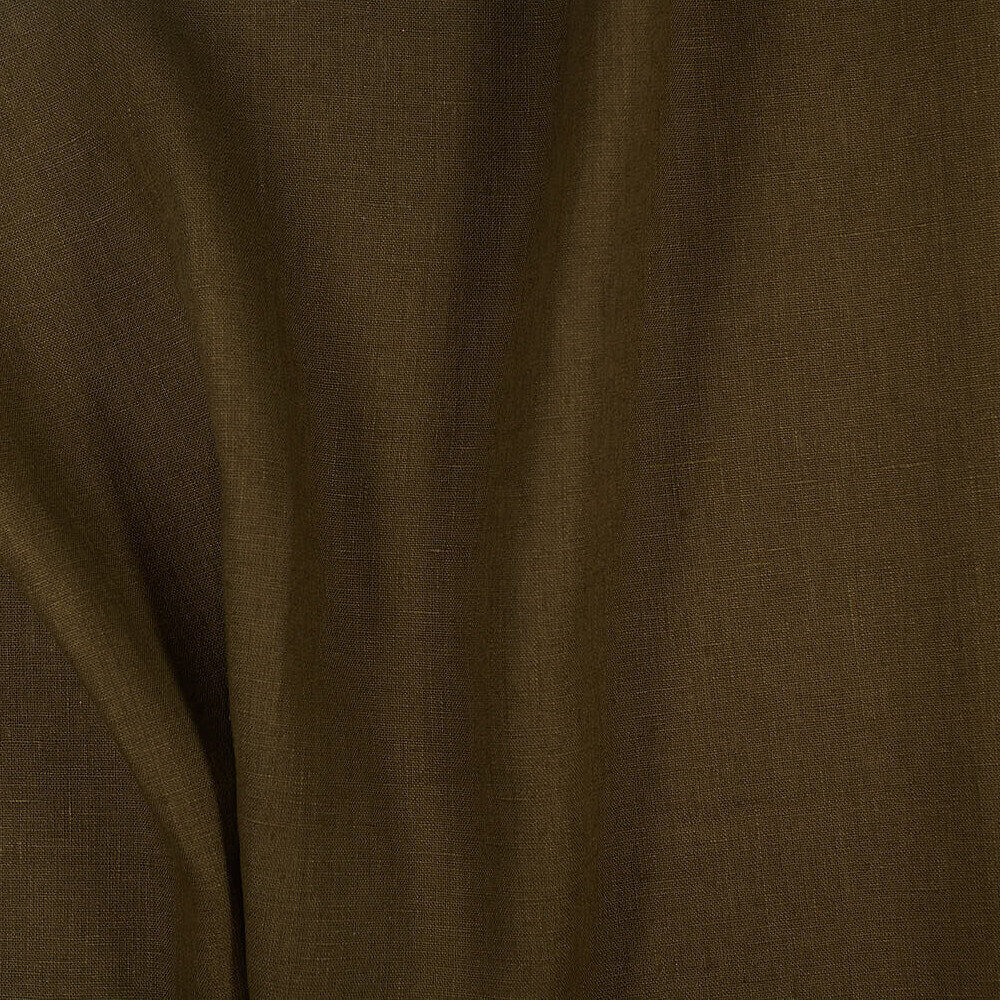

FS Colour Series: Olive Inspired by Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Earthy Naturalism

French artist Jules Bastien-Lepage was one of the greatest Naturalists of his generation, painting the French countryside with muted, earthy shades of moss green alongside soft tones of beige, brown and peach. Olive Linen’s warm, rustic shade of dark green was a favourite in his limited colour palette, lending his canvases a relatable down-earth-quality that celebrated the quiet wonder of nature and the people who lived amongst it. “Beauty,” he wrote, “is exact truth: neither to the right nor the left, but in the middle.”

Born in 1848, Bastien-Lepage grew up in the small rural village of Damvillers in the Meuse region of France and he never forgot the rugged naturalism of his childhood. From an early age he showed a great aptitude for sketching, copying from life various ordinary objects on the kitchen table including lamps, jugs and inkstands, learning the fundamentals of working from life under the guidance of his father, an amateur artist. In 1867 Bastien-Lepage earned a place at the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-arts in Paris, where he scooped up various prizes for his prodigious drawing talents, but his early years as an artist were less successful as he struggled to find wider recognition.

Taking part in the Franco-Prussian war left Bastien-Lepage severely wounded, both mentally and physically, but the act of painting suddenly took on a profound new meaning, acting as a potent salve to the traumas of the past. Early paintings from this period demonstrate the escapist delight he took in conveying textured surfaces and sparkling light with an almost photographic level of detail, which caught the eye of leading art critics and collectors and earned him critical acclaim.

Throughout the mid to late 1870s Bastien-Lepage focused predominantly on two core subjects: portraiture and rural everyday scenes. In contrast with the light, airy and colourful Impressionist painters rising to prominence around him, Bastien-Lepage was more steeped in the French Realist art of Gustav Courbet and Jean-Francoise Millet – like them his emphasis was on the ordinary naturalism of working life, celebrating hard work and manual labour as the backbone of French society. Bastien-Lepage returned to his home village of Damvillers to paint much of his most prominent art of the period; his paintings convey a deeply felt pathos for the landscape and the people who inhabited it.

The painting October, 1878 demonstrates Lepage’s remarkable ability to capture the close harmony between people and the land, and to celebrate a simple, everyday activity as two women gather potatoes from a muddy, trodden field. The subject is made magical through a harmonious balance of moss green, dusty blue, dark brown and off-white, as the women’s bodies and clothing almost become one with their surroundings. Bastien-Lepage also hints at underlying symbolism within the image, as the young woman’s precariously balanced basket becomes an exercise in restraint and control.

Made just a year later, the majestic Joan of Arc, 1879 was dedicated to the great war heroine, but rather than portraying her as a pillar of strength and defiance, Bastien-Lepage deliberately downplayed the enormity of his subject by setting this scene within Damvillers, and asking a local teenager to model for him. Instead, it is the garden around her that carries the story, a wild, overgrown tangle of trees and bushes painted in microscopic detail, where deep shades of earthy green intermingle and hide mysterious spirits within their depths.

By 1879 Lepage was becoming recognised as an eminent Naturalist painter amongst wider European circles and his art had a particularly profound influence on the Glasgow Boys in Scotland, who echoed both the muted, earthy colours and the quiet, pensive symbolism of Bastien-Lepage’s art. Of all the rural paintings Bastien-Lepage made before his untimely death at the age of 36, his portrayals of children in the outdoors are among the most celebrated and best-known. The melancholic Pauvre Fauvette, (Poor Fauvette) 1881 sets a young girl alone within a barren winter landscape, where bare, skeletal trees and branches overpower her tiny blanketed frame and dark green and brown grass forms a prickly and uninviting carpet around her. Pas Meche, (Nothing Doing), 1882 is more playful and downbeat, as a young barge boy is caught seemingly off-guard on his way home from work, casually leaning to one side. His deep brown clothes and hair are tinged with flickers of dark green, making them merge with the surrounding scenery, and it seems as though this well-trodden dusty path is the boy’s entire world. But his distant, anticipatory gaze suggests otherwise, a reminder, perhaps, that beyond the manual labour he is still a young boy who needs time and space to dream.

Leave a comment