Anna Andreeva: Fabric for the Future

Russian designer Anna Andreeva made a remarkable contribution to textile history, looking to the future with designs based on radio waves, electricity, algorithms and op art. Much like her predecessors Lyubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova, Andreeva combined the playful, abstract geometry of Russian Constructivism with industrial manufacture, spreading her ideas far and wide for the public to enjoy in their clothing and homes. But Andreeva’s contribution was all the more extraordinary because she determinedly continued to work with abstract, experimental motifs throughout the Soviet era, at a time when Stalinism had almost entirely erased avant-garde, abstract artistic practices in favour the propaganda style, figurative art of Socialist Realism. Under the seemingly innocuous guise of textiles, Andreeva staged a quiet revolution, noting how, in contrast with other art practices, “Textile was the territory of freedom.”

Born into a wealthy family of Russian aristocrats in 1917 as Anna Prasolova, Andreeva faced obstacles against success from an early age. When she was just seven years old her family home in Tampov was seized by the Red Army following the Bolshevik Revolution, and she was forced to hide with distant relatives in Moscow. Later, as she approached adulthood, her hopes for studying architecture at the Soviet Architectural Institute were dashed when her family’s bourgeois history saw her being barred from entering under the Stalinist ‘proletarianization’ programme. Instead, Andreeva managed to secure a place at Moscow’s Textile Institute. Textiles were deemed by the government as a less ideological and transgressive medium due to their associations with decoration and domesticity, a stance which gave Andreeva a surprising amount of freedom to experiment with a wide range of styles.

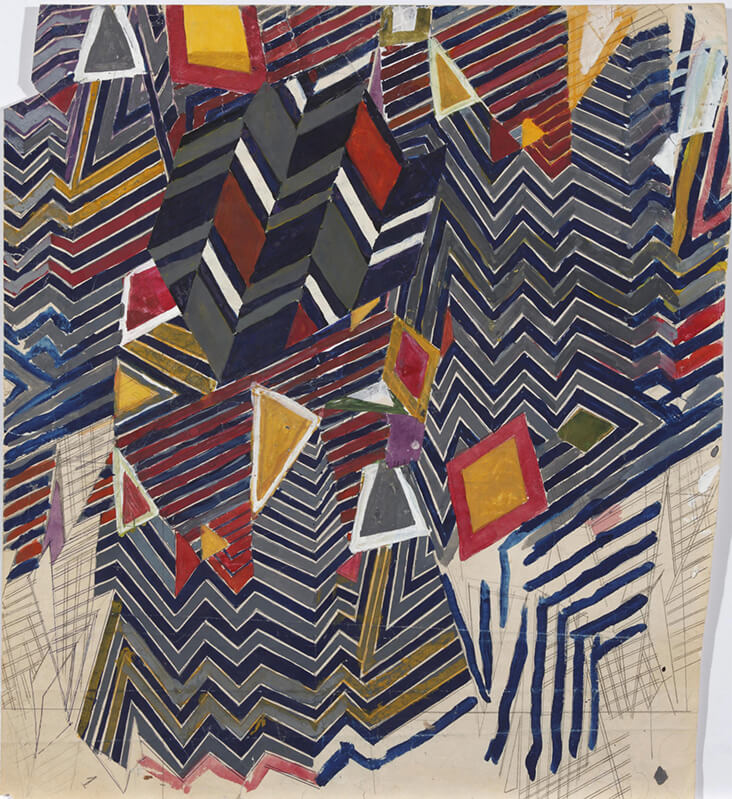

Following graduation in 1941, Andreeva found employment at Moscow’s prestigious silk factory Krasnaya Roza in the centre of Moscow. As Russia’s flagship textile manufacturer, the company had a reputation for fostering and encouraging design talent and Andreeva flourished under their leadership. Here Andreeva first began to play with geometric repeat patterns that illustrated the order and rationalism of the industrial world. She also explored relationships between textile patterns and fabric capacities, playing with the ways geometric motifs responded to differing thread thicknesses and interwoven intervals.

In a letter to her husband, the scientist and exiled dissident Boris Andreev, she described the privilege she felt to be working here at the forefront of the city’s leading manufacture, surrounded by the whirring, clanking world of textile machines, writing, “The sound of textile machines is obsessive. I dream of it and I love it.” Urban life was also a constant source of fascination and Andreeva refused to leave the bustling city of Moscow, even after the birth of her daughter Tatiana. “I have an urban mind,” she would tell friends and family – she later dedicated the pattern design Hello Moscow, 1960 to her beloved city.

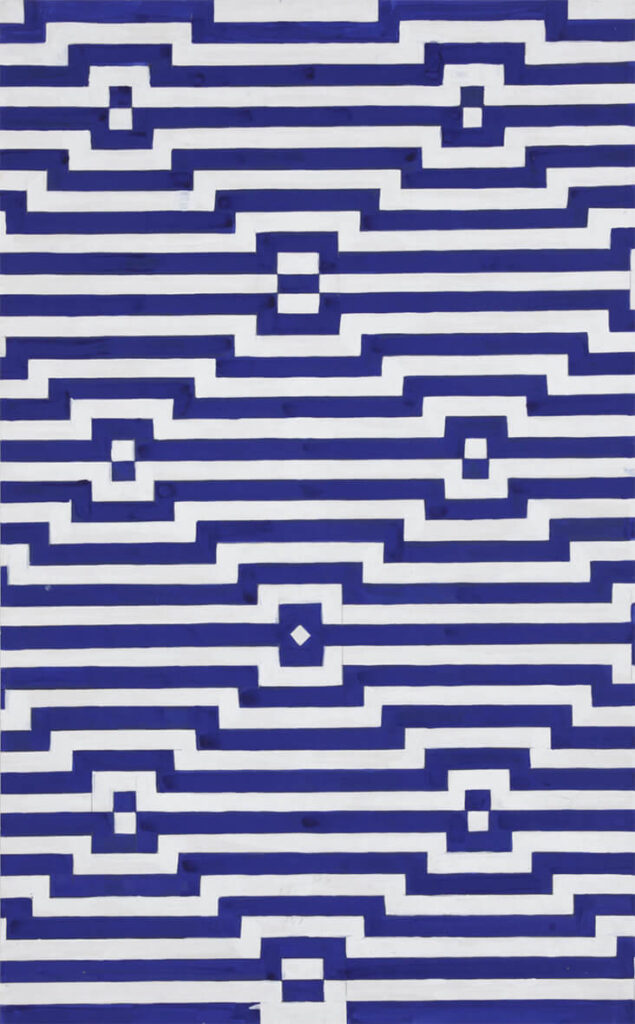

After the war Andreeva’s designs became ever more adventurous, combining various reference points including mathematical equations, symmetry, grids and algorithms, layered into rational, ordered motifs. From the 1970s onwards Andreeva collaborated with her mathematician and designer daughter on a series of dazzling, Op Art style designs that reflect a fascination with the glossy sheen of industry and technology, including the Electrification and Radio Waves series’. Andreeva’s career was not without challenges, and she was at times criticised by state censors for an “anti-proletariat” stance and for promoting the “pure propaganda of abstraction”, but she fought hard to have her designs approved. When her Electrification series, with its shimmering patterns of blue and silver stripes faced a backlash, she argued back, “Communism equals – the industrialization and the electrification of the entire country”, demonstrating how her designs reflected a progressive Socialist vision under a different guise.

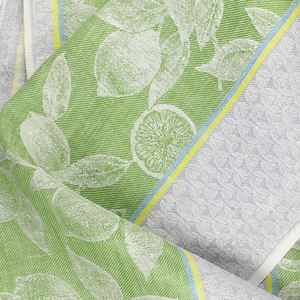

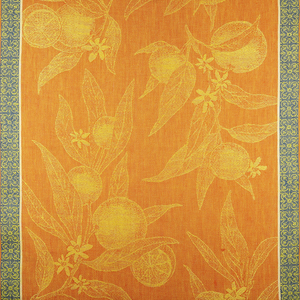

Along with design for mass production, Andreeva was also commissioned by the state to produce exclusive decorative textiles designed to represent the USSR abroad – many were not for sale, but reserved instead for diplomats, international celebrities and film stars. The first of these was the commemorative scarf design Glory to the First Cosmonaut, 1961, designed to celebrate Yuri Gagarin’s space voyage – Gagarin even presented the scarf to Queen Elizabeth II as a gift during his visit to London. Following the success of this project, Andreeva went on to design a secession of commemorative designs for International exhibitions, festivals and sports competitions including the Union of Technological Youth and the Moscow International Film Festivals.

Chairwoman to the Textile Section of the Moscow Union of Artists in her later years, Andreeva was a tireless campaigner on the importance of textiles, and following on her legacy she has inspired generations of Soviet textile artists to follow, not just with her striking, futuristic patterns, but her willful and restless determination to have her voice heard. But perhaps most importantly, Andreeva proved, throughout her long and prolific career, just how interwoven textile design truly is with the political and ideological landscape of its time.

2 Comments

Gaye Elder

I thoroughly enjoy Rosie Lesso’s posts and particularly appreciate this one one Anna Andreeva. In my art history studies I saw references to Constructionist art, but it rarely received more than two sentences of discussion and the same drawing or sculpture always seemed to be used as illustration. Seeing these textiles is not just interesting but intriguing. They inspire me to try to find out more about that movement. Thank you!

Rosie Lesso

Thanks so much for the positive feedback!