A Brief History of The Scroll Pattern

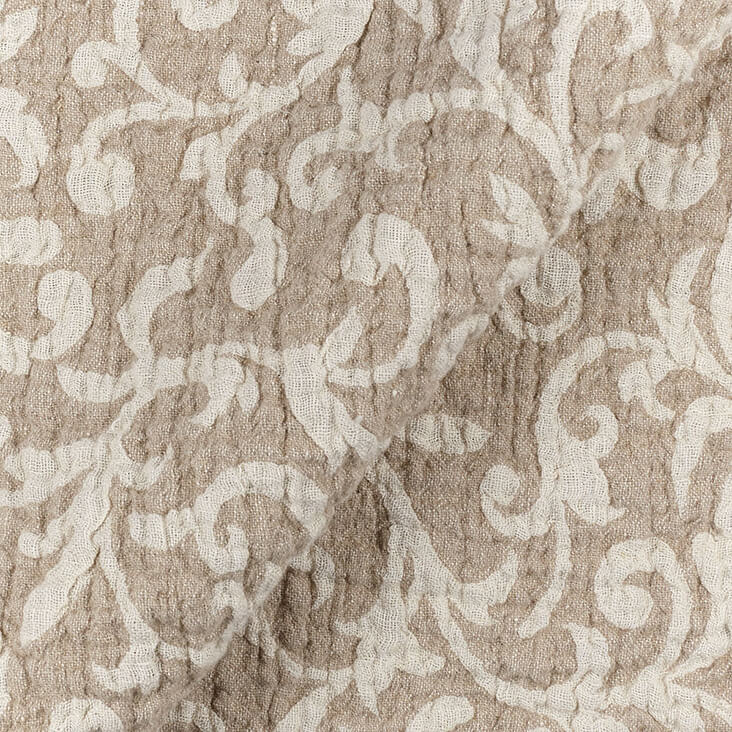

Intricate and ornate vines unfurl across Scrolls IVORY NATURAL Linen’s jacquard damask like fervent plant forms sprouting new life. This pattern is part of a long tradition of ‘scroll’ design, defined by flowing plants that form incomplete spirals in symmetrical repeat patterns, invoking the sensation of constant flow. From Greek pottery to Roman architecture and the Islamic arabesque, scrolls are deeply embedded into our cultural history. In Histories of Ornament: From Global to Local, 2016, authors Necipoglu Gulru and Alina Payne argue the enduring popularity of this motif is because scrolls “apparently do not succumb to gravitational forces, as garlands and festoons do, or oppose them, in the manner of vertically growing trees. This gives scrolls a relentless power.”

Scroll patterns and ornamentation have existed in our culture for millennia; examples were found in the Palace of Knossos at Minoan Crete from around 1800 B.C., but some believe the Egyptians and Mesopotamians also adorned architecture and textiles in scrolling patterns based on the observation of real plants, sometimes featuring fruit, animals and birds. Many Roman Stucchi also featured ornate curling leaf or plant-based patterning, which would later have a profound impact on the Italian Renaissance.

But when scroll patterns were adopted by Muslim artisans in around 1000 A.D. recognised plant or animal forms became increasingly streamlined or abstracted. In the following centuries a wide variation of scrolls became a defining feature of Islamic art, as eternal spirals came to represent the unifying order of nature. Plant-based designs were immensely popular and became ever more ornate and stylised as designers toyed with the creative freedom offered by scrolling leaves and flowers. Repeat patterns of floral motifs based on lotus and peony flowers were culturally significant in Chinese civilisations as damask textiles and other decorative design work – these, in turn, came to inform Islamic art throughout the 13th century.

Margaret, Duchess of Norfolk / Hans Eworth / 1562 / The frame is carved with strapwork and oval cartouches bearing arabesques.

In Ottoman ceramics and textiles of the early 15th century scrolling leaves and flowers were arranged into densely packed designs. Textile designers became proficient in weaving more complex designs, prompting a wave of plant- based Ottoman textiles. Europe picked up on the trend; scroll patterns were adopted throughout the Renaissance period and have persisted ever since. The French term “Arabesque” meaning “Arabian” was invented to describe this Eastern inspired aesthetic that pervaded Europe, adorning architectural stonework, illuminated manuscripts, furniture, textiles and walls from the 16th century and beyond. In a 16th century French dictionary, the arabesque was also concisely described as “rebesque work, a small and curious flourishing.”

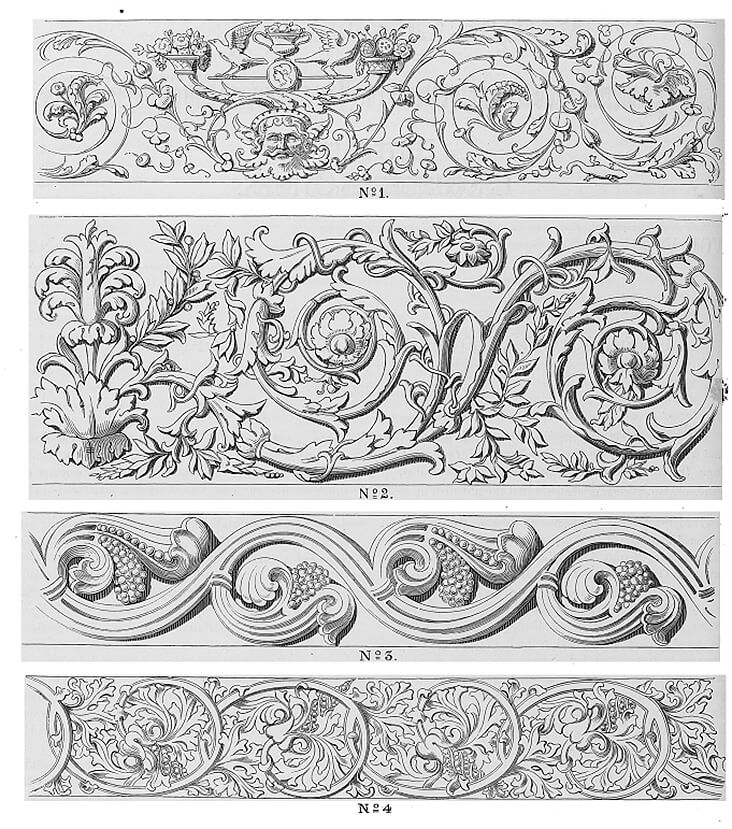

Renaissance styles invoked the same intertwining, sinuous branches and leaves as earlier Islamic styles. Into their careful, symmetrical arrangements they also introduced greater detail and ornamentation, incorporating acanthus leaves, feathers and flowers. Many designs were replicated as painstakingly hand-crafted brocades in repeat patterns, which adorned interiors and came to epitomise sumptuous and indulgent luxury, making them hugely sought after. Art historian Professor Stockbauer in The Arabesque of the Italian Renaissance, 1875 later praised designers of the period for their ability to invoke the abstract spirit of nature, writing how it “is based on a lively appreciation of nature, and demonstrates a delicate sense and acquaintance with the general phenomena of vegetation…” With the introduction of the jacquard loom in the 19th century, woven textiles featuring scroll and arabesque designs became increasingly widespread, and have remained so ever since.

In the early 20th century Art Deco, Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts styles drew inspiration from Islamic and Renaissance scrolls and arabesque patterns. William Morris and his contemporaries mimicked and further accentuated the ornate floral stylisations of earlier centuries with whiplash curls and intricate leaves arranged into ordered, symmetrical patterns, adorning all manner of media from ceramics and glassware to textiles and embroidery. Since then, the scroll pattern has retained both its associations with Renaissance luxury and a link to the Islamic focus on nature, harnessing an inimitable quality of endlessly flowing, circular energy.

2 Comments

Elaine Rutledge

At the June, 2020 Behance Online Creativity Conference (sponsored by Adobe) Kelli Anderson shows video of a jacquard loom. The images are of a loom in Deutsches Technikmuseum in Berlin.

The segment is part of the video “Materials for Computer People” by Kelli Anderson, noted designer and paper engineer. Please remove if referral to another site is not allowed. My feelings won’t be hurt.

Masha Karpushina

Hello Elaine, I’m not entirely sure what you are referring to.

Please elaborate on how this info relates to our article?

thank you.