Fear, Comfort and Catharsis: Tracey Emin’s Confessional Quilts

“Quilt-making involves a lot of thought and love. Just the time involved in the process means many things are discussed and considered concerning life.”

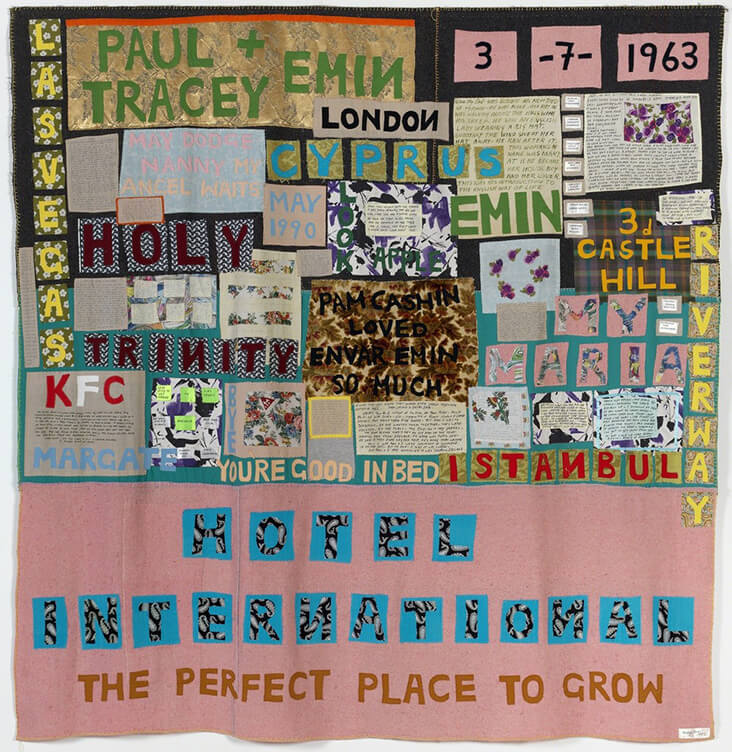

Art is a powerful form of catharsis for British artist Tracey Emin, one that has allowed her to express and process painful experiences from her past. More than any of the other hugely varied materials she has explored, including drawing, printmaking, sculpture and neon lighting, appliqued fabrics have been the most consistent, dependable and instantly recognisable strand of her practice. Initially designed as comforting bed blankets, they contain her innermost desires and fears; so much so, she even cried when her first quilted blanket, Hotel International, 1993, was sold.

Known today as the “bad girl of British art”, Emin’s difficult upbringing has become the cornerstone of her art. Born in Croydon in 1963, Emin grew up in Margate with her twin brother and single mother, who ran a successful seaside hotel. Much of their lifestyle was funded by Emin’s Turkish father, who had another wife and family on the other side of town. When Emin was young he abandoned Emin’s mother entirely, taking all their money and leaving them in financial ruin.

Emin was a wild child growing up and left school when she was just 13. At the same age, she was sexually assaulted, a trauma that came to play out in her art later in life. After several years spent drifting, Emin eventually found a way to study fashion at Medway College of Design in Rochester from 1980 to 1982, where she first learned skills in sewing and applique. Despite her lack of qualifications, her design and artwork was strong, and she gained a place to study a BA in fine art at Maidstone College of Art, before going on to a Masters at the Royal College of Art.

Though Emin destroyed much of her student and early career artworks following two traumatic abortions, sewing remained a vital strand in her art. Her first quilts came about almost by accident; after being offered a show with Jay Jopling’s gallery she began chopping up old clothes, some from her childhood, others from the closets of her friends, combining a range of vintage florals with blocks of bold colour. Likening the complex, layered designs to the act of painting, she commented, “I have always treated my blanket-making more like a painting in terms of building up layers and textures.” Initially imagining her quilts as bed covers, she insisted on calling them blankets, a word which invests in them a greater sense of comfort and intimacy. Her first, Hotel International, 1993 is emblazoned with mementoes from Emin’s childhood, including the names of people and places from her childhood, and even stitched in passages of handwritten memories.

Branching out into other surfaces, Emin appliqued a chair in There’s a lot of Money in Chairs, 1994, and made waves a year later with her embroidered tent, Everyone I Have Ever Slept with, 1995. The interior of her infamous tent held names of everyone Emin had shared a bed with, including boyfriends, her grandmother and even her brother, stitched in colourful, patchwork designs. Read literally by critics as a symbol of Emin’s promiscuity, the work caused quite a stir, which was instrumental in the development of her career.

By the 1990s Emin had become part of the burgeoning Young British Artists Movement, known for their confrontational and uncompromising art. The intimate language of her earlier quilts came to play in the hugely controversial My Bed, 1998, a supposed replica of Emin’s real bed, containing rumpled, stained sheets and what one critic called “uncomfortable personal debris,” including pill packets, cigarettes, used condoms and dirty underwear. What some saw as a crude excuse for art, others compared with the creased, folded sheets of Romanticist painters such as Jean-Dominique Ingres.

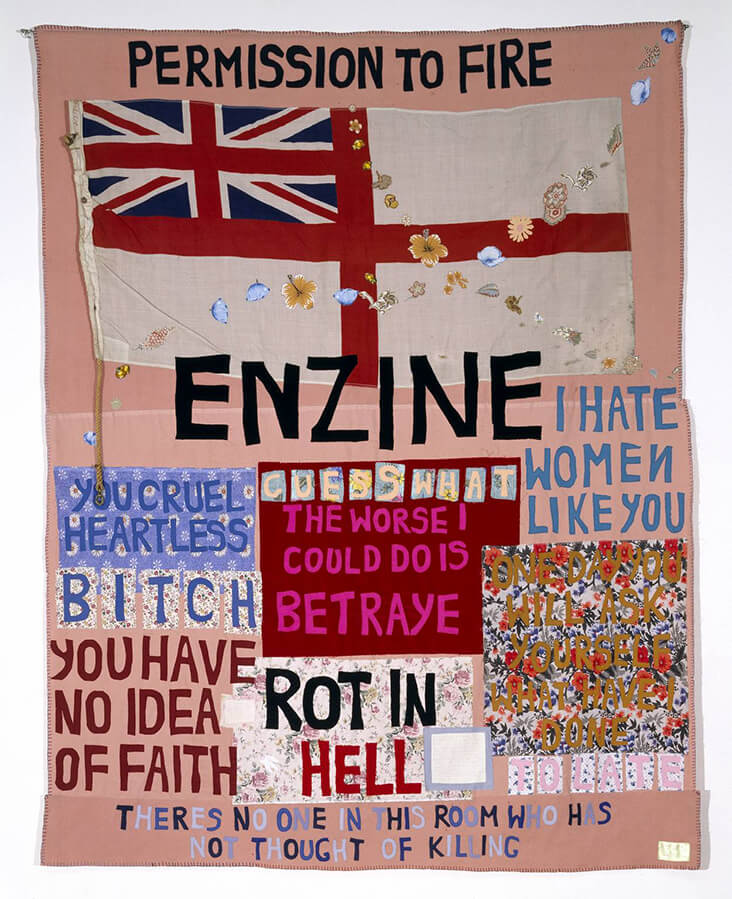

Since then, Emin has continued to make appliqued blankets, honing her trademark cut out lettering and clashing patches of vintage floral fabrics, while deliberately provocative, political or sexual content gives them a subversive edge. Many also feature the union jack, a potent symbol of Emin’s place in the Brit-art phenomenon of the 1990s. In the installation To Meet my Past, 2002, Emin tempers her earlier, unmade bed with a little-too-perfect one, covered in embroidered, hand-made fabrics, although each blanket is littered with tales of a troubled childhood marred by poverty and abuse.

In 2004, French designer Longchamp invited Emin to design a series of bags for their brand; without falling into commercialism, Emin developed the theme of “International Love”, a reference to a fictional character who travels the world looking for love. Today, many have argued Emin’s blankets are the most skilled, distinctive and unique strand of her practice, and therefore her greatest legacy. She writes, “Quilt making has always been considered a craft. It’s never been held up in the realms of high art. But I hope, I feel, that my practice has managed to change some of these conceptions.”

2 Comments

Cassandra Tondro

Great article! Thank you.

Vicki Lang

Beening a quilter myself this article pulls at my heart strings. Love the vibrant colors and messages Emin uses on her blankets.