Speed, Community And Craft

Recently in Tribeca, New York, an innovative café opened. It encourages customers to pick up their beverage and leave the shop without paying. No queuing! The consumer pays at their own convenience via text.

I emphasise the café example as it focuses on networks and their relationship with trust. The Tribeca drugstore is reconnecting long held social norms – of trust and community – to a contemporary urban experience. These ingredients are important to social cohesion. A cohesion that is often reported as stretch to its limits today.

I think craft excels in creating trust and cohesion. Design and craft have always created social networks. From artisan communities and collectives to makers-fairs, sewing groups. Apocryphally at least, the Stars and Stripes were born out of such a sewing community.

All of these examples are built on a practice of trust and, in part, this is created by the emotional bonds we build with places of craft making. Think how often you link craft to place? A benefit of looking at a broader historical perspective in Craft is to unearth why craft today reemphasizes, or reconnects us, to making and makers. And why this important. We can focus on one historical development which can be seen as synonymous with both craft and industrial development but at opposite ends: fast and slow.

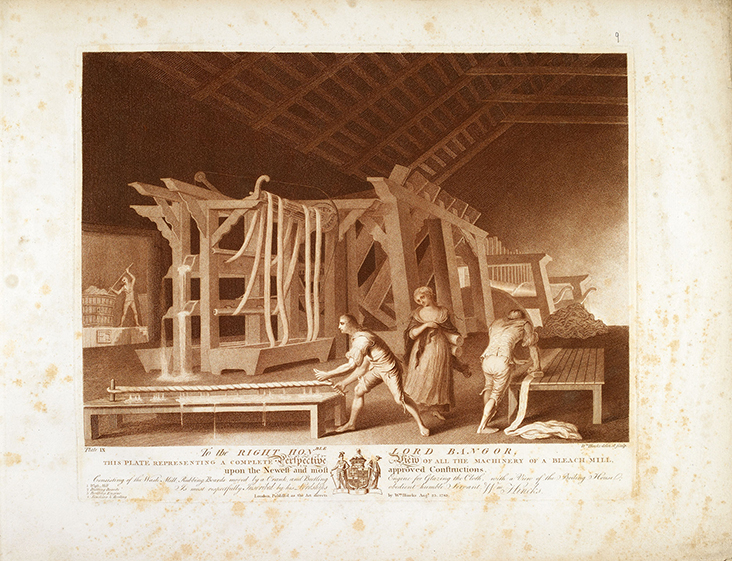

It is useful to focus on the effects and manifestations of speed. Speed is emblematic of a 20th Century attitude toward both a sense of place, and of craft. Historically the waterways of Europe and the United States were a source of both inspiration for artists to investigate nature; or in the case of the new canals: a pragmatic way to ferry goods from town to city; city to continent. Rivers and canals were usurped by the new networks of trains, subways, and motorway systems. Thus, by the early 20th Century, Craft and artisan networks were largely dismantled.

Travel and commerce networks are illustrative of how speed is used to deskill and disenfranchise communities. Put simply: The Butcher, Baker and Tailor become commuters rather than localized artisans. Large industry and commerce became a magnate which attracted to itself the people who sustained traditional cottage industries.

Equally, the notion of Place, is manifestly different in the new Century: The first tube maps of London simply had a meandering blue contour to designate the Thames (which was not even credited by name); while the new underground lines crisscrossed the map. The same can be seen in cities from Paris and Berlin, to New York. From the 1930s onwards, a culture develops which is obsessed with the new and, to the detriment of craft design; speed. Europe and America are remapped to accommodate speediness rather than cultural traditions of craft making.

During this period of change a tussle between arts and crafts, and the modernity of materials is witnessed: iron and glass for instance, vying with wood and calicos. The choice of materials is also influenced by the speed of production.

It is a legacy which continues well into the 20th Century. In the 1980s Italy we have the Memphis group: architects and designers experimenting with the new industrial materials – plastics and colour; whilst in England we have traditional furniture makers like Ercol. Promotional material of this time comments ‘Ercol use technology in every aspect of their furniture making. But they use it to enhance the judgment of the Craftsman’ The sentiment echoes the writings of William Morris a century before. Post swinging 60s fashion too, looked to craft and textures in London boutiques such as Barbara Hulanicki’s Biba. Nowadays the correlatives might be Kartell in Italy, and in the UK, the furniture of the Galvin Brothers or the fashion of Margert Howell.

Industrial manufacturing is synonymous with speed, whilst craft carries the notion of leisurely – if not laissez faire – production. But ‘slowness’ has taken a positive turn over the last decade or so. Where once, in the 1930s, Futurist artists implored Italians to stop eating pasta as it would ‘slow them down!’ Today, Italy is a founding promoter for the slow food movement!

The dichotomy between machine, and man-made, is succinctly captured by David Pye, in his book The Nature and Art of Workmanship. The book is a heartfelt investigation into design processes. He untangles the differences between handmade and mechanically produced design. I love his distinction between the two: workmanship of risk [handmade], and workmanship of certainty [mechanical]. The book champions the risk of mistakes – or the non-reproducible – in the hand made.

It is the irreducible and non-reproducible which is important to the bond we have with craft: the dropped stitch in textiles, scarification in ceramics, or pontil marks in glass. All provide the honesty of human trace. This human trace allows craft to be something we can invite into our lives – not simply as consumption, style, or intellectualism but as a conduit to emotions. Craft can connect to our own predicament. Craft is never didactic, it uncoils possibilities and fallibilities which, at its best, reconnects us with human networks, and cultural experiences.

Next, we will examine the touch and feel of craft making and how this underpins the emotional bond with well-crafted things.

Feature image: Roman Canal, Lincolnshire / Peter De Wint / c.1840

One Comment

Vicki Lang

Wonderful article about craftmanship and a slower time. The artwork of that time showed the slower life.