FS Colour Series: Rim inspired by Georges Braque’s Soft Fawn

RIM linen’s tawny, warm grey features heavily in French Cubist Georges Braque’s palette, as patches of fawn light are cast across dimly lit scenes, creating stillness and tranquillity. Though his early paintings were awash with Fauvist colour, it was Braque’s later, steely grey canvases that defined him as a true pioneer of early abstraction, one who explored patterns of closely toned light that seems to shatter before our eyes. On the narrowing of his creative playground to sombre, muted tones, he wrote, “Limitation of means determines style, engenders new form, and give impulses to creation.”

Born in Argenteuil, France, Braque spent the early years of his life in Le Havre. Following on the family trade for painting and decorating he took on an apprenticeship with a master decorator in Paris, while simultaneously pursuing evening painting classes at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. The side act became the main show when Braque discovered his innate artistic abilities, setting his sights on becoming an artist. After studying for several years at the Academie Humbert in Paris his paintings followed the rising avant-garde trends, first for Impressionism, and later for Fauvism, with expressive brushstrokes and heightened colours defining his first solo show in 1908. Braque first met Pablo Picasso in Paris in 1907, and slowly the pair would develop an intense, tumultuous friendship that would come to define both their careers in the years that followed, so close, Braque later described them as “two mountain climbers tied together.”

Both artists were fascinated by Cezanne’s late paintings, particularly his broken, multiple viewpoints, which they saw as closer to the fleeting nature of human sight than the singular perspective and static viewpoints that had populated art history. Ideas about disjointed perspective and fragmented forms became the cornerstone of their Cubist practice, particularly in the early, analytical stage, where they sought to capture scenes and objects through essence, not likeness. Both artists pared back their colour range too, allowing form, light and space to shine through. In Braque’s The Church of Carrieres-Saint-Denis, 1909 we see Cezanne’s influence with muted greens and sandy yellows, but Braque’s colour range is softer and quieter, as if surrounded by misty fog and sombre, grey light that weaves across architectural shapes and breaks them apart.

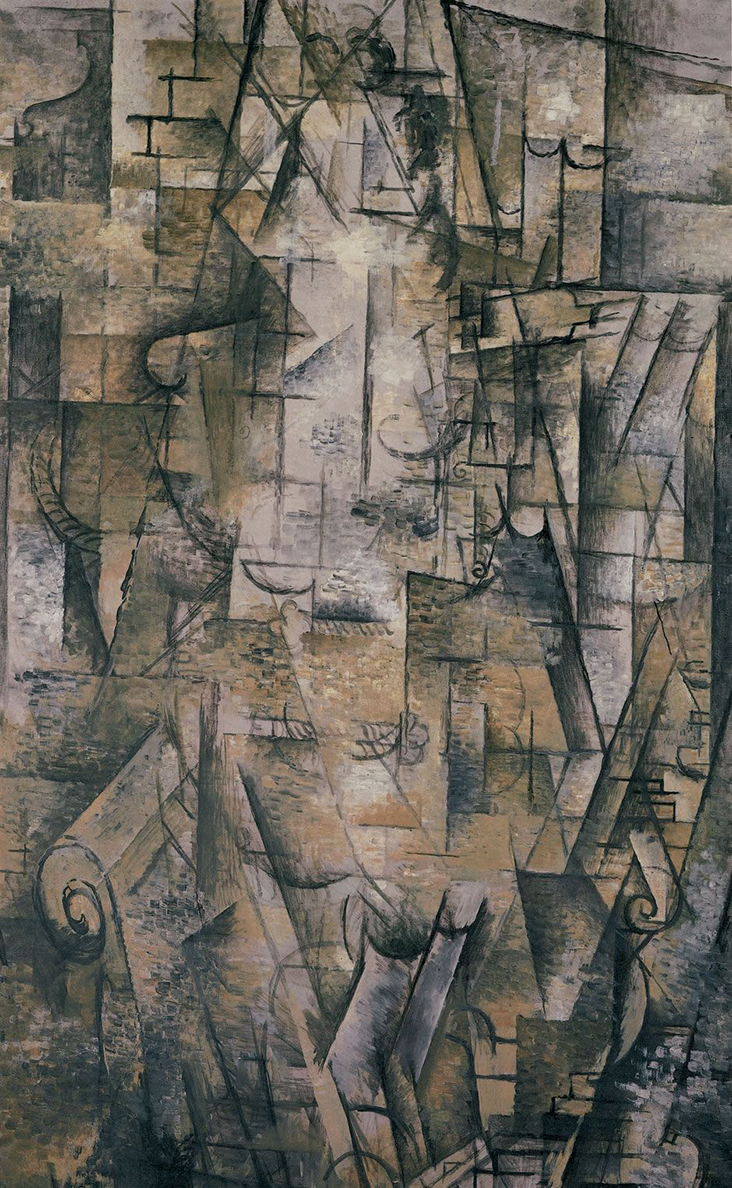

Still life was a popular subject for Braque, particularly musical instruments, with their full bodied forms that he could pull apart and reconfigure in experimental new ways. In Broc et Violon, (Jug And Violin) 1909-1910, two ordinary household objects are transformed into a field of shimmering, silvery grey light like shards of metal caught in a rainstorm, as the alchemy of the creative process lifts them into another realm. Braque reflected on his working process as filled with discovery and wonder, writing, “I never know how it will come out. The picture makes itself work under the brush… A picture is an adventure each time.” By the time he painted Femme Lisant (Woman Reading), 1911, black lines and warm strands of grey weave in and out of one another, rendering any subject unrecognisable.

After the First World War, Braque’s intimate friendship with Picasso cooled as both moved in new directions. Braque’s work became less stylised and more realist as his method of Synthetic Cubism, combining elements of collage, emerged, yet he retained the soft, muted tones and flat, geometric shapes of his earlier Cubist work. In the lively painting Still Life: Le Jour, 1929, we see a wider range of colours, yet it is the enveloping warmth of the rich, grey-ochre that brings life to the scene as it undulates across the table top, around objects and into the intricately patterned wallpaper beyond.

By the 1930s Braque had gained international fame for his fresh, abstract canvases that transform commonplace objects into scenes of mystery and wonder. Table top scenes continued to occupy his mind, which he painted as flattened forms with subtle tonal modulations, including Fruits Sur La Table (Fond Gris), 1935, where meltingly soft, warm grey light flows in and out of the scene suggesting just the slightest hint of sunlight flooding in.

During the Second World War, Braque’s paintings reflected the dark times he was living in as his scale shrank and colours became even more stripped back and muted. Just a year after the war ended adventurous patterns and larger scales flooded back in, as seen in the expansive The Billiard Table, 1945, where broken panels of texture and colour spread across the picture plane into a tapestry-like design. Colours are still characteristically subtle, with warm fawn greys suggesting the diffused light of a closed interior, drawing us in to search again and again for hidden meanings within this quiet, mysterious scene.

One Comment

Vicki Lang

Once again you have brought to light a wonderful painter. Thank you for your informative articles.