Yayoi Kusama: Finding Infinity

“I followed the thread of art and somehow discovered a path that would allow me to live.”From paintings of miniscule, showered dots to psychedelic body art and rooms of infinite light, Kusama’s art presents a complex world that exists just beyond reality. She has become a worldwide phenomenon in recent decades, ranking as the most expensive living artist in the world today, while in our selfie-driven, Instagram culture gallery goers have flocked in thousands to photograph themselves in her famous Infinity Rooms. But beneath the gloss, rivers of pain and suffering run through Kusama’s art. Since childhood her art has taken on a curative quality, allowing her to momentarily silence the inner demons that torment her. She wrote, “I fight pain, anxiety and fear every day and the only method I have found that relieves my illness is to keep creating art.”

Kusama was born in Japan, the youngest of four children to a wealthy family who owned a large seed farm, growing exotic varieties of flowers to sell all round the country. Yet her childhood was deeply unhappy – raised by parents in an arranged, loveless marriage Kusama’s father was a serial adulterer, which had turned her mother into a bitter and enraged figure of contempt. She would sent the young Kusama to spy on him and report back what she saw, after which Kusama says, “…my mother would vent all her rage onto me.” Kusama’s nascent desire to be an artist rather than a Japanese housewife also enraged her mother; if she caught her daughter drawing the family flowers she would hastily rip the work from her hands.

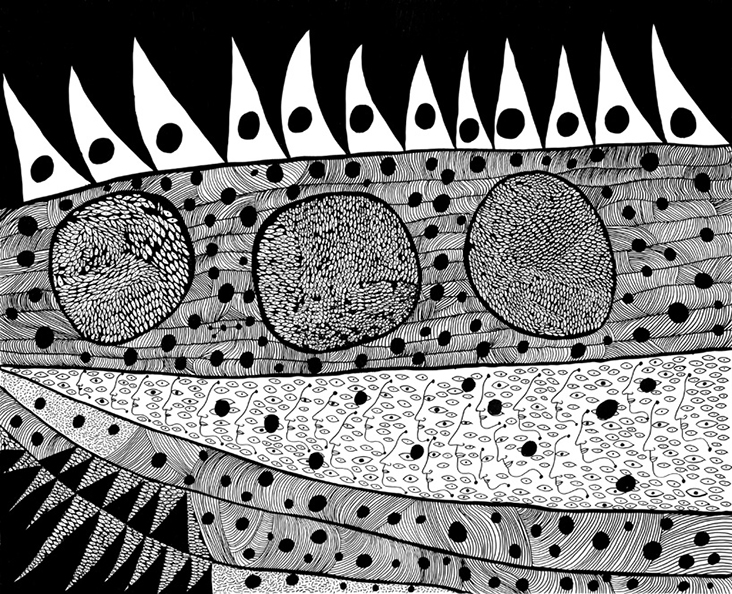

At the age of 10 Kusama began having terrifying hallucinations, often in which auras of light or dense fields of pattern would engulf her vision or chase her through her house. She remembers a particularly harrowing incident as if straight from Alice in Wonderland, when the flowers she was drawing turned to her and started talking, writing, “I had thought that only humans could speak, so I was surprised the violets were using words. I was so terrified my legs began shaking.” These hallucinations stayed with her throughout her childhood, but she found drawing could normalise her visions and make them seem less threatening, as she explained, “Whenever things like this happened I would hurry back home and draw what I had seen in my sketchbook… recording them helped to ease the shock and fear of the episode.”

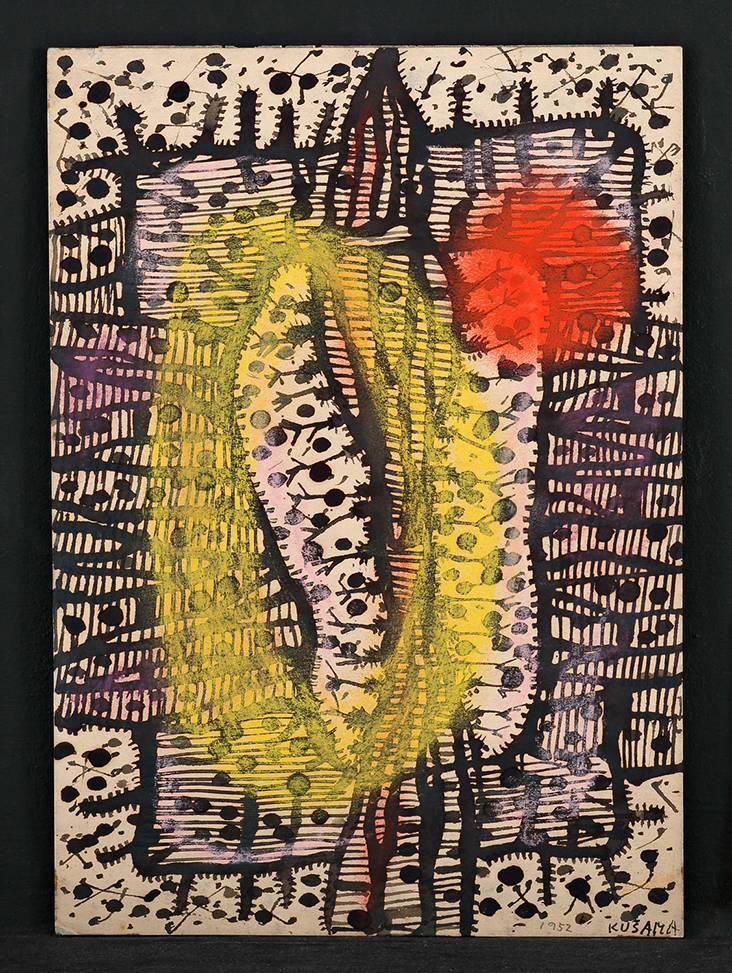

During World War II 13 year old Kusama was sent to work in a Japanese military factory sewing fabric together for parachutes, learning sewing skills that would later be translated into her art. She found the horrors of working in a darkened factory as air raid sirens and army planes blared around her terrifying, a traumatic experience which would stay with her for the rest of her life. After the war, Kusama’s mother allowed her daughter to attend the Kyoto School of Arts and Crafts, but only on the strict condition that she also attend regular etiquette classes. Kusama had no intention of learning etiquette and she soon tired of the traditional 1000 year old Nihonga teaching methods at Kyoto. Instead she trailed around her favourite bookshop, reading about American Abstract Expressionism and studying Georgia O’Keeffe’s paintings.

After hunting down O’Keeffe’s address, Kusama began regularly writing to her, sending her watercolours of exploding seed pods and asking for advice on how to make it in New York, to which O’Keeffe replied, “In this country an artist has a hard time making a living. You will just have to find your way as best you can.” By 1957, at the age of 27, Kusama was ready to follow her dreams and give life in New York a try – on her way out her enraged mother told her “to never set foot in this house again.”

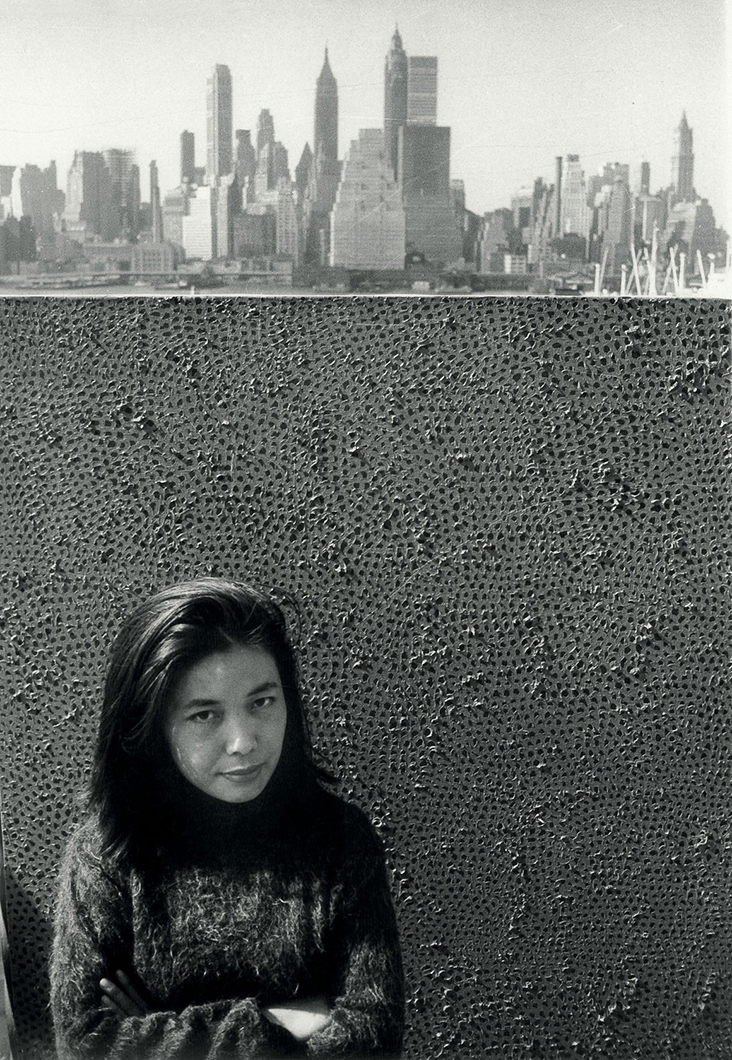

O’Keeffe helped Kusama find galleries to show her work in New York, but her life was still marred with extreme poverty. With only several hundred pounds and 60 silk kimonos to sell Kusama survived on fish heads scavenged from the dump which she boiled into a broth, while sleeping on an old door for a bed. Yet even so, she found the creative culture she had so craved for years, reflecting, “For art like mine, (Japan) was too small, too servile, too feudalistic, and too scornful of women. My art needed a more unlimited freedom, and a wider world.” A breakthrough came when she began making her Infinity Net paintings, made from tiny repetitive loops in intricate designs based on her fantastical childhood hallucinations, which caught the attention of Minimalist artists and galleries.

Kusama also developed close ties with her contemporaries around her, befriending Minimalist artist Donald Judd when the pair both lived in the same building in Manhattan, often visiting each other’s studios and chatting together long into the night. The older sculptor Joseph Cornell was deeply infatuated with Kusama, sending her an endless stream of poems, holding lengthy phone conversations and inviting her to stay at his house where he still lived with his mother. Yet Kusama’s friendships with Judd and Cornell remained platonic. After witnessing her father’s extramarital affairs and her mother’s responsive rage Kusama admitted having an aversion to sex, writing, “My fear was of the hide-in-the-closet-trembling variety. I was taught sex was dirty, shameful, something to be hidden…” adding, “I happened to witness the sex act when I was a toddler and the fear that entered through my eye had ballooned inside me.”

Installation view of Kusama in Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field, at her solo exhibition “Floor Show” at R. Castellane Gallery, New York / 1965

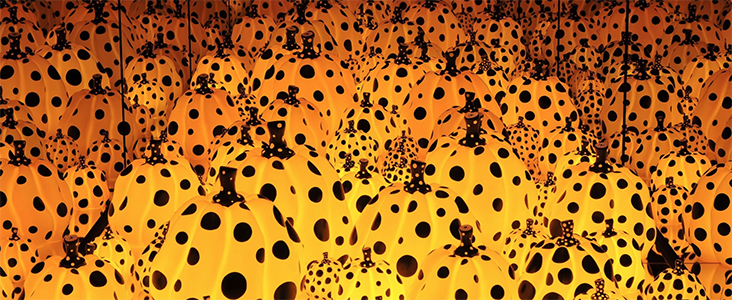

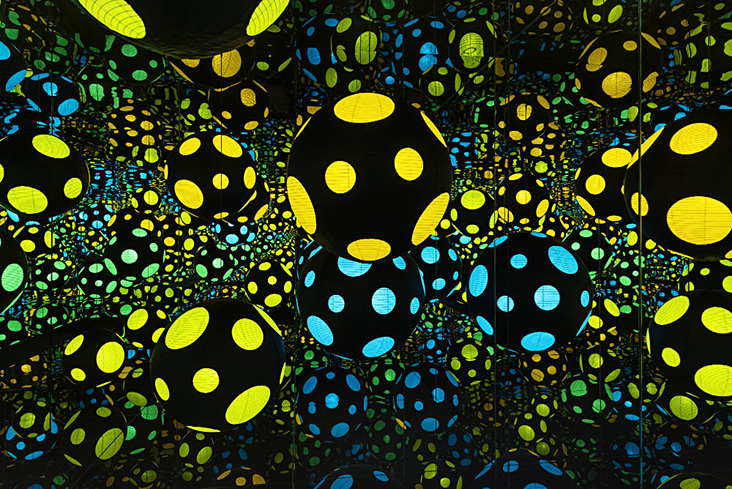

Such intimate fears came to the fore in Kusama’s practice when she began covering ordinary objects with protruding, phallic forms made from stuffed fabric, including chairs and boats, early examples of her “soft sculptures”, which were also read by many as an attack on the male-centric nature of the New York art scene. In one exhibition Kusama blew up a photo of her surreal, phallus covered boat and had it printed as a repeat pattern wallpaper across a gallery wall. Kusama also began her first Infinity Rooms in the 1960s, which she continues to develop today, in which viewers enter a mirror-lined, dimly lit room alone as light refracts around them, creating the illusion of infinite, endless space and reflecting on our insignificance in the face of the vast universe. Dots often appear in these installations on sculptural objects that reflect into limitless fields of colour and light, as a symbol of life, planetary forms or miniscule particles, as Kusama writes, “My life is a dot lost among thousands of other dots.”

Though she was beginning to garner a reputation within the art world, Kusama was well aware that her position as a Japanese woman fighting for her place in a patriarchal system was fragile. Her struggles only aggravated her mental health issues and in her darkest hours she even made several suicide attempts. Kusama watched from afar as her white male peers, whose ideas closely overlapped with, or copied hers, were achieving far greater levels of recognition, security and success. In a recent film biography of her work, Kusama – Infinity, made by Heather Lenz in 2018, Kusama points out how both Claes Oldenberg’s fabric sculptures and Andy Warhol’s printed wallpapers were lifted from her practice, though raising these issues causes uncomfortable ripples amongst the art establishment, as Lenz points out, “Obviously I checked all the dates and they all work out as she said. People who had degrees in art history still challenge this though; it was as if they don’t want to shift their views.”

Ramping up the desire to be heard, Kusama became increasingly prolific in the later 1960s, spanning a huge range of media including drawing, painting, writing, sculpture, performance, fashion and installation. An extreme workaholic, she was said to have often painted all night, sometimes working for 50 hours straight, though she was hospitalised several times for exhaustion and struggled to make any sort of living from her art. During these years Kusama became notorious in the press for her flamboyance, organising naked happenings, walking through New York’s roughest neighbourhoods in full Japanese costume or selling small reflective balls at the Venice Biennale which she called “your narcissism for sale.” In a series of “Body Festivals” Kusama painted people’s naked bodies with her trademark dot patterns, later selling scandalous costumes with holes for breasts and buttocks. Kusama even famously wrote to President Richard Nixon offering to sleep with him if he would end the Vietnam War.

By the early 1970s the media circus surrounding Kusama’s practice had led her to develop a notorious reputation in New York and she struggled to be taken seriously, particularly when America’s political climate became more conservative under Nixon’s second leadership. This, coupled with the death of Cornell and her own mental exhaustion led her to return to Japan in 1973, yet even there she had become a social pariah, labelled as the “shame of Matsumoto City.” When her father died several years later her mental health took a major toll and in 1977 she admitted herself into the Sewei Mental Hospital, where she has been living by choice since this time. In Sewei she attended art therapy classes and worked on a series of collages in homage to Cornell, while she spent a huge amount of time re-evaluating her life and art, referring to this period as a time when she had to rebuild her life again from the ground up. Biomorphic forms slowly appeared in her art, particularly the pumpkin, which, with its curious eccentricity, became a symbol of Kusama’s alter-ego.

Though she continued to make art, for over 20 years Kusama was almost completely forgotten by the art world, until the International Centre for Contemporary Arts in New York organised a major retrospective in 1989. Since then, both her earlier, and more recent art has steadily grown in popularity, reaching staggering heights of success in the last two decades that she could only have dreamed of in her youth. Major solo shows have been staged in locations around the world including Mexico City, Rio, Seoul, Taiwan and Chile, while in 2017 a five storey building was dedicated to her life and work in Tokyo, a museum so popular visitor numbers have to be capped every day. One of the most popular works in the museum is her famous Infinity Room Pumpkins Screaming about Love Beyond Infinity, 2017, a series of dotted, glowing pumpkins that seem to stretch out into an endless universe.

At 90, Kusama continues to create work in a studio near Sewei Hospital, where she has no plans to stop anytime soon, writing, “Even now, there isn’t a single day when I’m not painting.” Though her nightmarish visions still haunt her she seems to have found a certain peace amongst them through her art, as she explains, “I still see hallucinations even now. Dots come flying everywhere – on my dress, the floor, things I’m carrying, throughout the house, the ceiling. And I paint them.”

Throughout her 60 year long career Kusama has had a profound and lasting influence on contemporary art, shaping not only the Pop Art styles around her in 1960s New York, but also the wave of Feminist and Fluxus performance art in the 1970s, for which she is finally achieving recognition. There is a decorative beauty to her art which makes it appealing to the commercial market; she successfully collaborated with fashion giant Marc Jacobs for Louis Vuitton in 2012, producing a hugely popular series of vibrantly coloured dotted clothing and accessories. Yet Kusama’s profoundly moving inner language is so intimately tied to her own troubled life that it is hard to imagine anyone else filling her shoes. In an interview in 2015 when asked to give advice to emerging artists, she encouraged them to look within, writing, “A true direction will come from overcoming adversity.”

One Comment

Vicki Lang

Yayoi Kusama has one of the most beautiful, tortured souls of any artist. Thank you for the wonderful article.