Ruskin and Morris: The Arts and Crafts Idealists

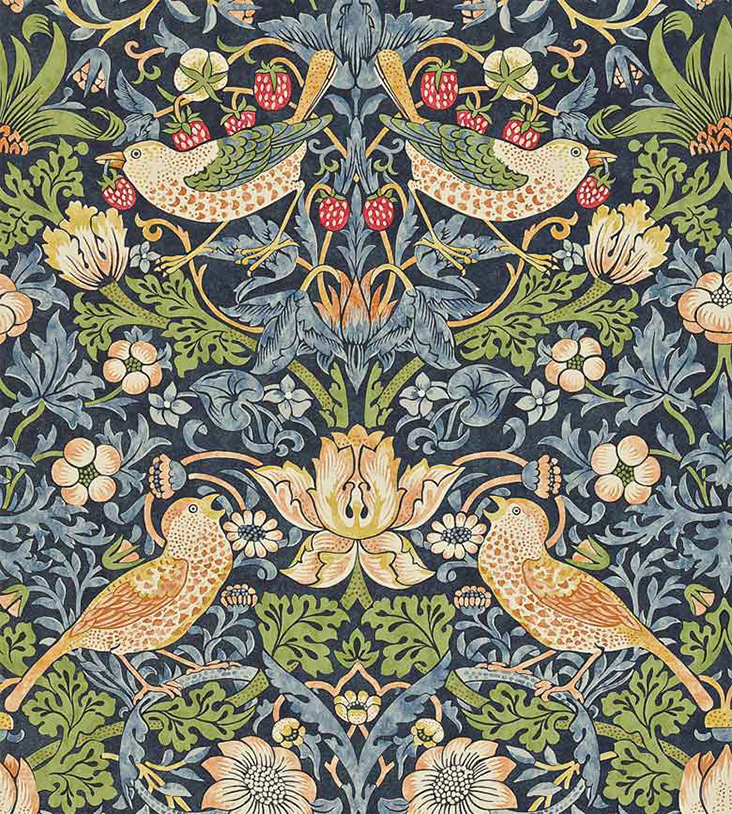

The naturalistic, floral patterns of the Arts and Crafts movement are such a firm favourite with the British establishment that it is easy to forget the idealistic, rebellious roots of the style revolution. Angered by the demoralising effects rising industry and mass production was having on British society at large, writer John Ruskin, designer William Morris and a whole generation of libertine artists, designers and writers that followed set about leading radical societal reform, marching towards fairer, democratic methods of production. Morris summed up the group’s moral and socialist ethos when he made a rallying cry for “art which is made by the people and for the people, as a happiness to the maker and the user.”

Ruskin was Victorian society’s leading art critic, who vociferously expressed polemic opinions on controversial subjects that were not always popular. He was horrified by the treatment of the labouring classes in the urban environment, where factories employed children as young as 8 years old and expected workers to complete back-breaking 12 hour shifts with few breaks and no holidays. The factories themselves, including textile mills and mines, were dirty, noisy and dangerous places that were destroying the mental and physical health of their employees.

Ruskin wrote prolifically on the subject of social reform, arguing such arduous, monotonous working conditions were dehumanising and demoralising, offering little room for creative expression or autonomy. In his publication Unto this Last: Four Essays on the Principles of Political Economy, 1862, he described Britain’s industrial society as a destructive force that was driving labouring classes deeper into poverty and unhappiness. For Ruskin, the solution to such problems lay in the art of the Middle Ages, where high quality products were made in small scale Guilds and workshop spaces which trained workers to take real pride and ownership in the objects they designed and produced. He believed that creative labour, channelling both intellectual and physical abilities, was the healthy foundation for a truly fulfilling society, calling for business leaders to take responsibility for their workers by “shaping the market” with fewer, well-made products that were designed to last.

The young William Morris first came into contact with Ruskin’s ideas as a student in Oxford and was profoundly moved. Seeing the potential for social reform in design, Morris moved on to train as an architect, later changing course to set up the interior and furniture design firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. with several friends. Through his design firm Morris and his colleagues, including Pre-Raphaelite painters Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and architect Philip Webb, believed they could entirely reform the production and dissemination of art and design.

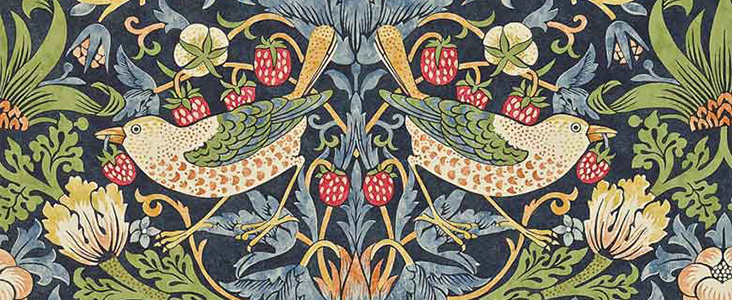

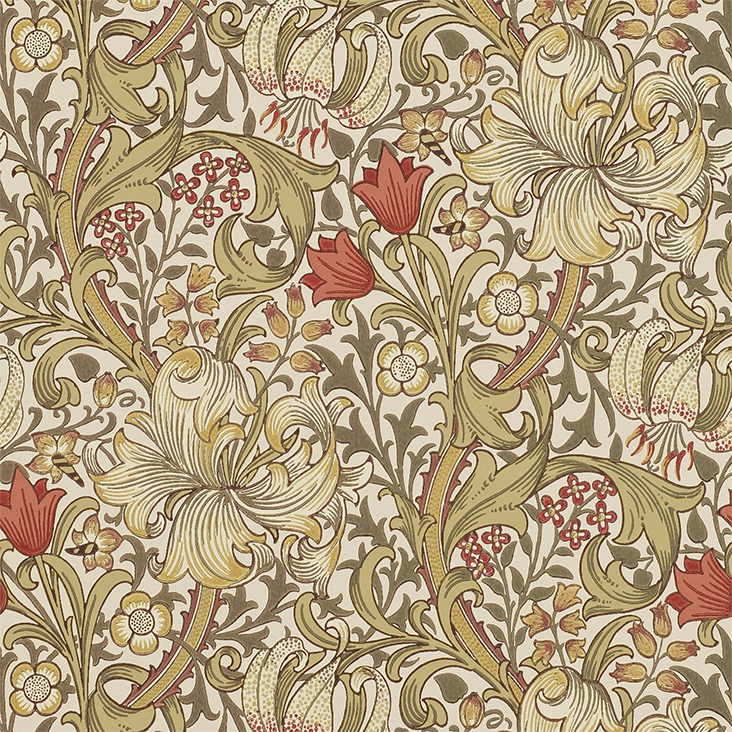

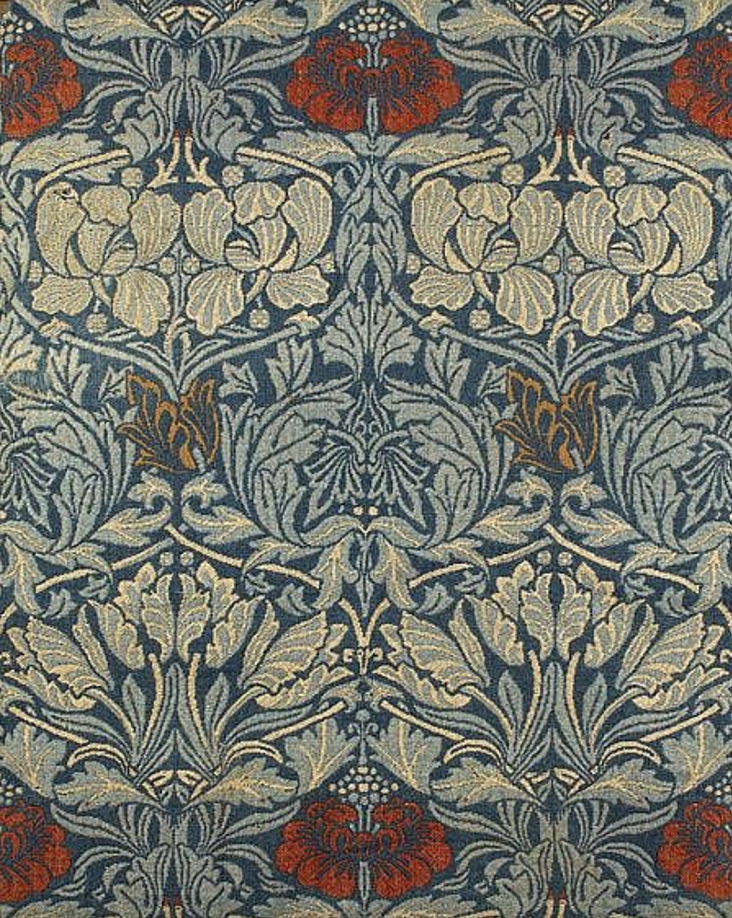

Together they saw art and design practices as indivisible, breaking down barriers between the fine and decorative arts by encouraging traditional skill and craftsmanship. Initially they produced stained glass, hand painted tiles, table glass and furniture, before branching out into providing a full interior design service, creating a vast array of wallpapers, printed and woven textiles and carpets. Most items were made in house using traditional machinery and processes, such as vegetable dyeing techniques, hand-woven carpets and hand-painted wallpapers, although Morris would sometimes sub-contract to larger companies – he was not against all methods of industrial production, but believed the process should be simplified and approached in a responsible way. Famous examples made by their company include the St George cabinet, designed by Philip Webb featuring decorative panels designed by Morris, as well as commissions for St James’ Palace and the Green Dining Room at the South Kensington Museum.

In 1875 Morris took sole ownership of the company, renaming it Morris & Co., with the aim of creating an art that could be affordable and accessible for everyone, as an art for everyday life. He wrote, “I do not want art for a few, any more than I want education for a few, or freedom for a few.” The company was oriented towards a working / middle class audience and became hugely popular, establishing shops in London and Manchester with goods produced at an active workshop space in Merton Abbey, Surrey.

By the 1870’s Morris’ influence was being widely felt across Britain, with decorative art practices experiencing a dramatic period of revival. The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society was founded in London in 1871, aiming to create regular showcases for makers to exhibit and sell their products, proving hugely influential and popular in the following years. First president of the society, illustrator and artist Walter Crane was a staunch socialist and a close friend of William Morris, describing the aims of the society in a powerful text written for the group’s first exhibition catalogue, which revealed a close continuation of Ruskin and Morris’ ideologies:

“The movement represents in some sense a revolt against the hard mechanical conventional life and its insensitivity to beauty. It is a protest against that so called industrial progress which produces shoddy wares, the cheapness of which is paid for by the lives of their producers and the degradation of their users. It is a protest against the turning of men into machines, against artificial distinctions in art, and against making the immediate market value or possibility of profit the chief test of artistic merit.”

Such ideas became widespread and influential, first across the UK and later in Europe and the United States. Various off-shoot societies for exhibiting decorative arts were developed, as were small scale workshop spaces and larger technical colleges teaching specific skill sets which could prepare makers for employment in industries such as jewellery, stained glass, weaving and furniture making, many which still exist today. In the long term, Morris’ aim to create an art for everyone was financially unsustainable – much to his deep disappointment he realised his art and design ware was catering to a wealthy audience, “ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich.”

But Morris’ socially responsible business model was hugely influential on methods of production in Britain, where hand-crafted techniques were revived and appreciated by a whole new generation to follow. The emphasis Morris and his Arts and Crafts colleagues placed on originality of design spread across Europe, helping define the Art Deco, Art Nouveau and Bauhaus styles of the following decades, as well as the American Craftsman Style and the Japanese Mingei movement. While such ideas were largely dissolved by the war, in the 1950s The Festival of Britain celebrated the Arts and Crafts influence that was still shaping an ethical strand of British and International design, felt in forms as varied as typography, furniture, architecture and textiles.

Today, various designers have tried to uphold Morris’ socialist beliefs, producing affordable items rather than inaccessible luxury products, including Terence Conran, who writes, “I have a Morris-like view about not producing things only the rich can afford.” But many of the issues about mass-production, consumption and capitalism raised by Ruskin, Morris and others are even more pertinent today than they were in Victorian times, with valuable lessons in their revolutionary idealism. Reflecting on their hugely important contribution to British culture, art critic Herbert Read wrote, “(Morris) rediscovered the artistic conscience, the most essential of all qualities in art.”

Join us next time when we will be looking in more depth at the influence of nature on the Arts and Crafts style and examining the ways the distinctive, decorative motifs continue to influence designers today.

5 Comments

Pingback:

Graphic Design History – IAART105 Graphic Design Process 02Maureen Castro

Thank you for today’s post on the Arts and Crafts movement by Rosie!! I thoroughly enjoyed it. While I’m writing, I’ll say thank you for all the tutorials, and beautiful patterns, too. Of course, the linen is beyond compare. I love everything I’ve ever bought from you. Keep up the lesson posts, please.

Sincerely, Mary J Wilder Smith

Maureen Castro

MAJOR kudos to who made the decision to incorporate Rosie Lesso’s knowledge and expertise into the FABRICS-STORE website. I love your product, your customer service (Maureen especially) is amazing, tutorials and patterns available are perfectly suitable for linen garments, shipment and the careful packing of fabric can’t be beat…and NOW my heart starts pounding when I see one of Ms. Lesso’s articles has been posted. I so enjoy and appreciate the effort to honor what we as customers and creative beings need to better understand the history of human endeavors in art/color. This serves to uplift and inspire all of us who follow in the same footsteps. Please pass my remarks onto your management.

Thanks again,

Laura Overturf

Judy Tepley

Our own times have segregated the designs and wallpapers, most interior design products into the realm of the upper class again. Wealthy can afford to decorate using his work but the low income worlds cannot. Not a Wm. Morris design insight for a modest budget. How would he feel about that?

Sherry Berbit

Beautifully written- so enjoyed this!