Arts and Crafts: A New Way of Life

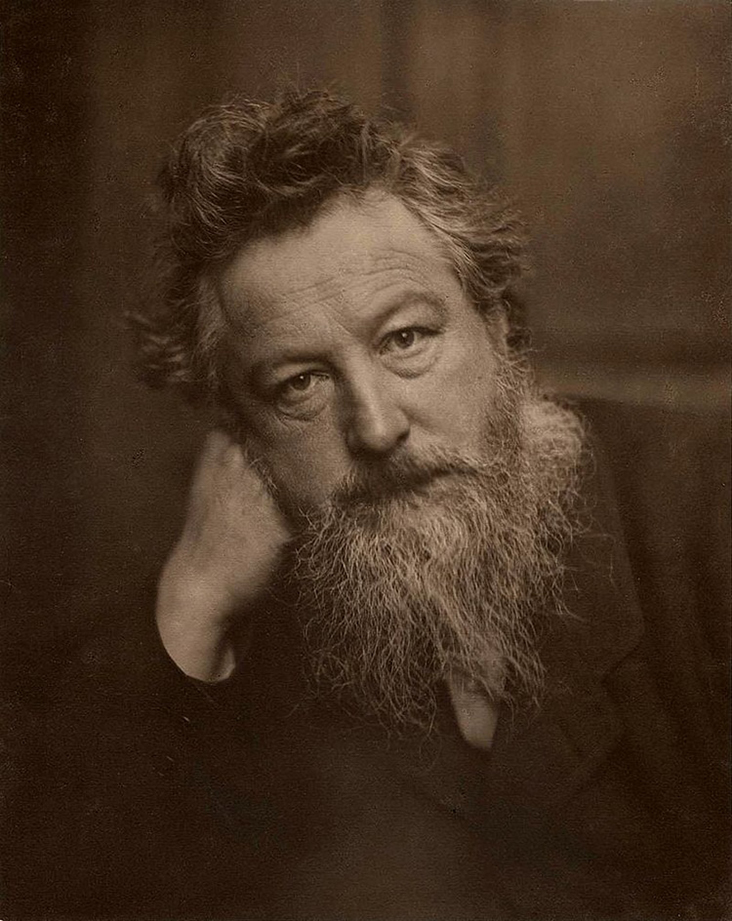

“Nothing should be made by man’s labour that is not worth making.” William Morris

In this new series we will explore some of the key ideas behind the iconic and hugely influential British Arts and Crafts Movement, a widespread phenomenon of the late 19th and early 20th century that continues to shape the world we live in today.

At the heart of the Arts and Crafts movement was a deep desire to improve society for the better. What began as a small, reactionary group promoting high quality craftsmanship over mass production quickly gained momentum, spreading across the UK into Europe, the United States and Japan, encompassing all strands of design including fabric, interiors, jewellery, furniture and architecture. With a socialist ethos the group’s leading members fought for quality over quantity, which they argued could improve working conditions, the standard of design and the aesthetics of people’s homes. William Morris, one of the group’s most prominent leaders, famously wrote, “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” The high levels of skill and originality of design they promoted elevated everyday, useful objects to the status of fine art, restoring dignity to aspects of design that were being homogenised by industry.

From the outset, idealism played a vital role in the development of the Arts and Crafts movement, although some ideals were more realistic and successful than others. London in the 1840s was suffering in the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, with factory-led mass production damaging both social standards and the quality of manufacture. Large numbers of labourers shipped in to the city were crammed into unsanitary, squalid housing and factory working conditions were dangerous, exhausting and underpaid, while factories pumped out pollution into the newly overcrowded city. Manufacture was becoming increasingly distant from designers, leaving many products lacking spirit and humanity.

A strand of frustrated intellectuals had begun to revolt against such changes in the mid-19th century, with a group in London banding together to form The Arts and Crafts Society in 1871, the basis of the movement’s name. Believing the decorative arts could radically transform society for the better, they advocated a higher standard of living, with offshoot groups establishing small scale workshops and guilds providing training and employment. Innovative, hand produced items were made that they hoped would be affordable for all, although the production costs proved too high for this to be sustainable long term. But together the group raised the value of decorative arts through regular exhibitions and displays which proved lucrative and popular, spreading their ideas far and wide. The first president of the society, artist and book illustrator Walter Crane, wrote, “The true root and basis of all art lies in the handicrafts.”

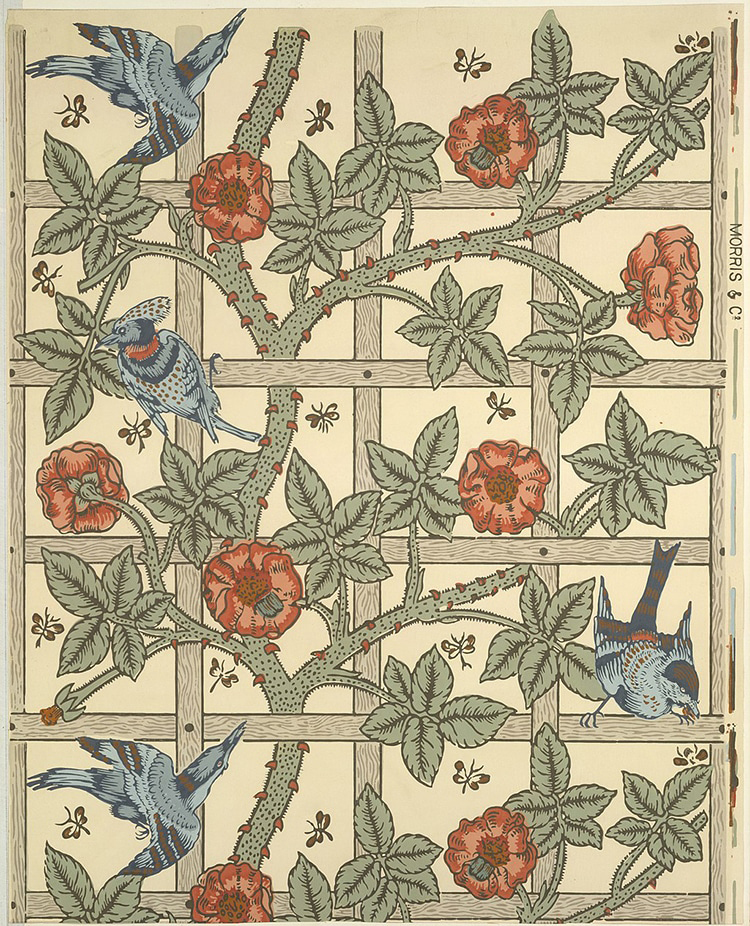

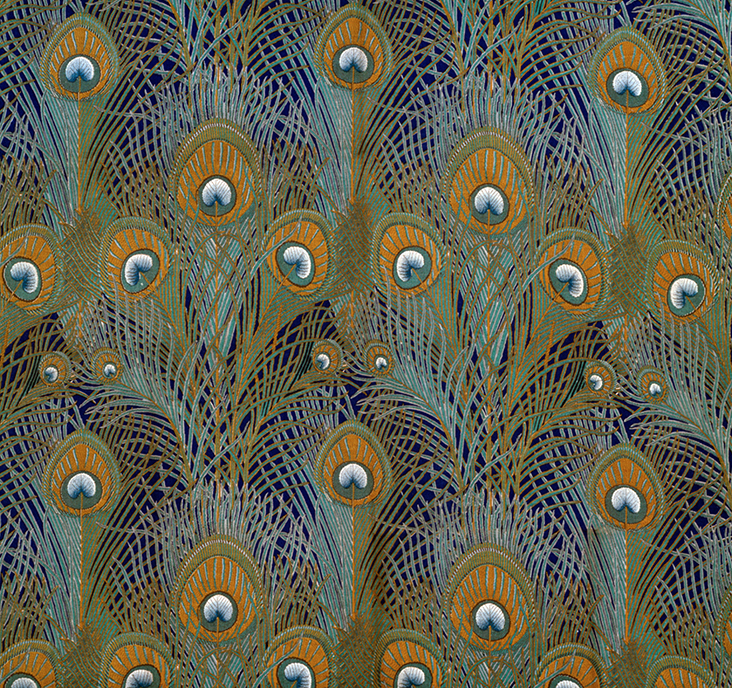

While the group were united through socialist ideas rather than aesthetics, nature became a recurring theme, seen in plant forms, feathers and floral decorations, as single motifs and richly layered, intricate repeat patterns. As a reaction against the depersonalising effects of industrialisation many of their densely patterned designs drew on vernacular plants and flowers from their native English countryside, including wildflowers and weeds. They celebrated the human need to connect with the natural world by filling interior spaces with decorative items including wallpaper, furniture, lamps and fabric. Some of the most popular fabrics to be designed include C.F.A Voysey’s distinctive patterns, Arthur Silver’s much celebrated peacock feathers for Liberty and Lindsay Butterfield’s floral textiles, decorating the homes of the British public. Such designs infiltrated the world of British fashion, which was initially ridiculed, but in following decades became the mainstream trend.

The intricate, curling tendrils in William Morris’ extensive design collection proved particularly popular, so much so that they have become synonymous today with the entire Arts and Crafts oeuvre. A passionate socialist, Morris began his career as an architect’s apprentice before moving towards interiors, founding the wallpaper company Morris, Faulkner and Co., where he saw the potential for taking art out to the people, to create an accessible art for all, saying, “I do not want art for a few, any more than I want education for a few, or freedom for a few.” Running his own company gave Morris the freedom to collaborate with other artists and designers, including Pre-Raphaelite painters Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and the architect Philip Webb, who all worked together to produce the integrative “total work of art” Red House, where Morris lived with his wife, a project described by Rossetti as “more a poem than a house.”

Together with the Pre-Raphaelite painters, Morris championed and helped spread the ideas of John Ruskin, the renowned writer and art critic. Ruskin rejected the rising capitalism of contemporary society, arguing for a return to the social structures of medieval society, particularly their focus on small scale guilds that apprenticed highly skilled workers to make lovingly crafted objects; these ideas led to the foundation of various new art schools teaching technical skills across the UK. He also celebrated medieval visual culture, which he saw as more in tune with nature and the human spirit, encouraging artists to revive illuminated texts, to take influence from close studies of nature as observed directly from life, and to revive Gothic styles, particularly in architecture, which he felt held a much greater “fitness for use” than grandiose Neoclassical styles. Stained glass was lifted from medieval times, with artists reinventing the technique into an expressive form of art, as led by the charismatic designer and teacher Christopher Whall.

The Arts and Crafts movement spread across the UK in the later 19th and early 20th century, driving the creation of over a hundred organisations based on Arts and Crafts ideas, including new art schools and technical colleges teaching artisan skills including enamelling, embroidery and calligraphy, as well as community based workshop spaces providing apprenticeships and employment, with many still running today. Arts and Crafts ideas spread from Britain to Germany and Austria, influencing the styles of decorative arts being made, to the United States in the early 20th century, where it adopted various names, including the American Craftsman Style and the Mission Style, and into Japan as the Mingei movement in the 1920s.

The socialist stance at the heart of the Arts and Crafts movement was revolutionary and affected the way design was made and appreciated around the world, allowing the decorative arts to infiltrate people’s homes, offices and public spaces with a unique human touch. Many cities developed garden spaces based around Arts and Crafts ideas which still exist today, such as the botanic garden at Darmstadt in Germany and Letchworth Garden City in England. Their melding of art and design led the way for subsequent avant-garde movements including Art Nouveau, Art Deco, the Bauhaus and the rise of 20th century Modernism, while an emphasis on skill and craftsmanship at the root of design continues to affect the way many products and designs are made today, as British organisations including Liberty and the V&A Museum will testify.

In an age of environmental damage, excess and climate change, the argument for cottage industries and handcrafts is more pertinent than ever, as V&A curator Karen Livingstone points out, “People today are …socially responsible and concerned about overconsumerism – and they want to escape the pressure of urban life.” Designer Dries Van Noten has picked up on this current school of thought, producing hand-blocked prints and textured fabrics, while designer Consuelo Castiglioni produces feathery accessories, delicate leaf patterns and earthy rustic colours and Christopher Bailey for Burberry has taken inspiration from his native Yorkshire, creating Autumnal, decadent prints reflecting the raw beauty of the English countryside. Livingstone sees the Arts and Crafts as an ideal antidote to the issues we face with industry today, saying, “It’s the right time – Arts and Crafts laid down a whole principle of living and working that has a resonance today.”

Join us next time when we will be looking in more depth at the role idealism played in the development of the Arts and Crafts movement, and the lasting impact it has had on design since.

12 Comments

Elaine Rutledge

William C Morris is a contemporary artist in Mobile, Alabama. His style is very different from the William Morris, textile designer, but he is equally acclaimed internationally. His painting of Mother Teresa hangs in the Vatican. He also happens to be my husband’s first cousin. You can see examples of his work here: http://wcmorrisart.com/

Maureen Medrano

Wonderful Article – Thank You!

Cat Tillotson

Very well written: thanks, Rosie!

Gigi Deroin

Thank you for a very interesting article. A revival of the sentiment behind the Arts & Crafts Movement continues in many small independent clothing lines as well as designers. More people are interested in creating their own garments, if only one or two unique pieces. I for one find it encouraging.

Lindsey Palmer

Well done Rosie. I look forward to your next article.

Madelyn Lenard

Oh the ones who take one word out of context and condemn an entire group without even knowing what was meant by the word “socialism” in the early 18th century.

Karen Pardue

Thank you for a thoughtful and informative piece!

Julia Fletcher

Its spelled Kool Aid

Sally Bussey

Morris “ a passionate socialist” …. with the freedom to run his own company… I smell cool aid. Oh the young and easily influenced. Please don’t let education teach you what to think but rather how to think… for yourself. Otherwise you just become another hypocrite promoting something called socialism for everyone but yourself.

Jane Henderson

Oh the elderly and entrenched. Please try and keep an open and inquiring mind, otherwise you are just drinking another flavour of cool aid.

Lindsey Palmer

How sad that this is what you got from this article. This man made a huge contribution to the world of art and textiles. His spectacular sense of design and color are unparalleled. He inspires me and I am neither young nor easily influenced. Just open minded and still willing to listen and learn.

Rosie Lesso

Hi there – thanks to everyone for taking the time to read and comment on the text! Sally, in response to your comment on Morris, I think it’s very important to note that in spite of his middle class, relatively privileged upbringing he was a hugely political figure and really tried to live out his socialist and Marxist ideals, and not just as a designer – the facts speak for themselves. If you are interested in finding out more please do read this article from the Socialist Review magazine which delves into his political involvement, as a speaker, activist and writer promoting socialism and Marxism in the UK: http://pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk/sr196/nineham.htm