Artisan Embroidery: Rosalind Wyatt

As we explored in our introduction and history of embroidery, using the craft to tell a story or document history has been common practice since its inception, the greatest example being the Bayeux Tapestry, which was created in around the early 11th century. Our next artisan embroiderer produces modern versions of this phenomenon, stitching stories into garments to create a textile representation of personal histories. Rosalind Wyatt creates this art in a digital age where people are concerned about how little they will leave behind, allowing their stories to come to life through her stitching.

Rosalind stitching. Photo: The New Craftsmen

Rosalind stitching. Photo: The New Craftsmen

Rosalind can trace her needlework skills back several generations into her own history – her grandfather and great grandfather were tailors on Savile Row and her Italian mother’s aunt did fine embroidery for couture. Rosalind started her own artistic career with a focus on calligraphy and bookbinding, but recognized a talent and passion for textiles, going on to complete an MA at the Royal College of Art in Textiles and Mixed Media. Moving from calligraphy to stitching wasn’t as much of a switch as a “œprogression” for Rosalind, where her range of writing tools just became broader. Rosalind says she discovered that “œit’s the intention behind making a mark that gives it power and presence”. One of the tools she picked up to write with was a needle and she began to form letters with it, finding her artistic voice in textiles and stitching.

Her first project in 2009 was “˜The Stitch Lives of Others‘ where Rosalind celebrated the lives of three generations of her husband’s family, the Tukes of York. The project brought together three things – lettering, life and art, and historical artifacts such as letters and garments provided her with the inspiration to create modern artwork out of these personal effects.

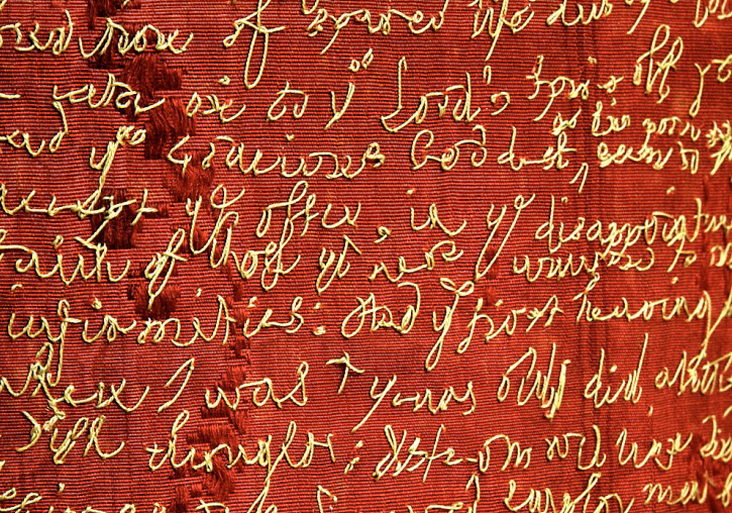

An extract of Rosalind’s’ intricate ‘trans-sewing’. Photo: The New Craftsmen

An extract of Rosalind’s’ intricate ‘trans-sewing’. Photo: The New Craftsmen

Part 1, “˜Tuke’, is an 18th century silk brocade bodice featuring the letters of Rosalind’s husband’s great, great grandfather Daniel Hack Tuke, a doctor who wrote to his father about the treatments he witnessed in asylums he visited with his wife Esther. The bodice was found amongst these letters and became the canvas for Rosalind to tell the story of Daniel and Esther, stitched in their handwriting, some in thread found in Esther’s own sewing box. Part 2, “˜Sainsbury’, is a traditional Japanese kamishimo that features stitched extracts from “œpassionate, poetic, obsessional love letters” written by Japanese playwright Torahiko Kori to his English lover Hester Sainsbury, Rosalind’s husband’s grandmother. Part 3, “˜Shunan’, is a jacket belonging to the child of Hester Sainsbury, Susan who is Rosalind’s husband’s mother-in-law; the piece is embroidered with Susan’s early drawings and childhood experiences.

Part’ 1: “˜Tuke” 18th century red, silk, brocade bodice Photo: Rosalind Wyatt

Part’ 1: “˜Tuke” 18th century red, silk, brocade bodice Photo: Rosalind Wyatt

After Rosalind finished this she was approached by individuals wishing to donate garments and items to explore their own families’ identity and lineage, which is now the ongoing “˜The Stitch Lives of London‘ project. This artwork is a collaborative installation telling the story of London through text and textile – Londoners donate their stories to Rosalind in the form of a garment and a handwritten document, which she then transforms into art. These pieces will eventually add up to be 100 meters long and hang together to replicate the path and shape of the River Thames, bringing the city to life using garments worn by diverse Londoners themselves.

The first pieces completed from this was “˜If Shoes Could Talk’, which tells the story of Mary Pearse, the troubled daughter of a London shoemaker. The garment is a pair of silk satin dancing shoes from the early 19th century – a pair which her father would have sold, but Mary would have been too poor to wear herself. The next was “˜A Boy who Loved to Run’ – a running top which belonged to a young boy named Stephen Lawrence who was murdered by a gang of white youths in South East London in 1993 because he was black. His mother, Baroness Lawrence of Clarendon, OBE told Rosalind about his running, achievements and how he lived for the moment; the running top features a school essay which stops mid-way through a sentence in order to celebrate his life rather than his death. There’s even a piece from actor Jude Law – the shirt he wore when he played Hamlet in 2009 on the London stage. Jude hand-wrote an excerpt from the Shakespeare play which Rosalind then stitched on the original garment.

‘If Shoes Could Talk’ from ‘The Stitch Lives of London’. Photo: The New Craftsman

‘If Shoes Could Talk’ from ‘The Stitch Lives of London’. Photo: The New Craftsman

Rosalind hand-stitches directly on to the garment by copying traces of its owners’ original handwriting in her stitch, which she calls “˜Trans-sewing” – writing with a needle. She says her hands become the “˜teller’ of the tale as she follows the “œpattern and rhythm of writing”. To Rosalind, anything we have worn bears our imprint, it has been close to our skin and carries the “œmarks and ravages of time”. Handwriting is also direct evidence of a person, it is a personal mark of their voice and the art of stitching “œcreates a subtle space where you can allow that voice to be heard”. For Rosalind, “œwhen text and textile come together, it gives a visceral sense of a human presence”.

‘A Boy who Loved to Run’. Photo: Feeling Stitchy

‘A Boy who Loved to Run’. Photo: Feeling Stitchy

The sense of life and human presence comes through her work in a strong way and acts as a snapshot of a person in a certain place and time. In a world where things move on so quickly and the physical is more and more fleeting, Rosalind’s work allows people to be brought back to life and for moments to live on, celebrated in a more permanent way. One of Rosalind’s favourite quotes is “œyou are a note in a world song” – a small part of something much bigger, but as important as any other and the world song is happening right now so should be acknowledged.

“˜I wish I were with you’ Commission for Fortnum & Masons, Piccadilly, London’ Photo: Rosalind Wyatt

“˜I wish I were with you’ Commission for Fortnum & Masons, Piccadilly, London’ Photo: Rosalind Wyatt

Rosalind has had many commissions in her artistic career, including the National Portrait Gallery and the British Council as well as calligraphy clients in Gap, Fendi, Burberry, Swarovski and Vivienne Westwood. A recent project for Fortnum & Mason depicts the iconic department store and its relationship with explorer George Mallory, telling his fascinating fatal journey to summit Everest in 1924 through the art of stitching. Rosalind also teaches and has lectured at the V&A, the BBC, Kew Gardens and The Art Academy, and remains involved in the community by encouraging Londoners to be involved with her “˜Stitch Lives of London’ Project. Rosalind herself will live on through her art, recreating history with her modern-day Bayeux Tapestry.

Part of ‘…because its there’ for Fortnum & Mason. Photo: Rosalind Wyatt

Part of ‘…because its there’ for Fortnum & Mason. Photo: Rosalind Wyatt

5 Comments

Bonnie

Stunning. Completely stunning. What a splendidly creative effort.

Thank you for helping so many to become aware of Rosalind Wyatt’s work, who otherwise would not have the opportunity to know of it.

(MimiB, and other smug detractors need to get a life; and those of us who have not been condemned to live inside MimiB’s skin and slag through life burdened with so critical a spirit, can only be grateful. Ms. Wyatt’s carefully exquisite embellishments would no doubt be joyfully celebrated by the original owners of the garments.)

Susana

Very interesting concept, and so timely to me. Just yesterday I stopped at a Chinese restaurant I’d never patronized before, and while waiting for my order, I studied a beautiful picture on the wall of a complex Chinese scene. Looking closely at it, I realized it was all embroidery on a neutral beige background. Clearly, these forms of needlework have universal appeal.

Rosalind’s work is especially intriguing in that she embroiders words to tell her stories. Beautiful!

Barbara Vickers

Many thanks for such interesting stories of the history of sewing.

Emily

This is incredibly beautiful work; very moving. Thank you for sharing her story with us.

MimiB

As someone who has worked to preserve and conserve old textiles and artifacts, I absolutely cringed seeing these photos.

I’m sorry, but defacing rare historic garments with crude, poorly executed modern embroidery is just wrong, despite the “artistic” impulse behind it. Please, don’t destroy any more 18th century bodices or 19th century shoes.