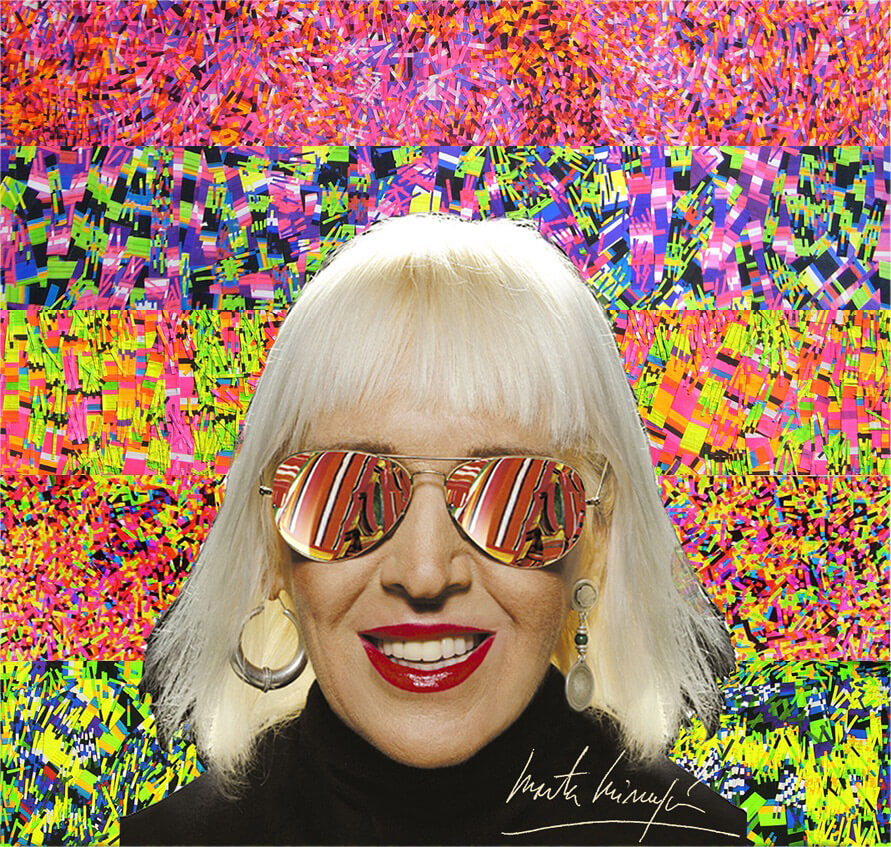

“Colourful, Carefree, Fun”: Marta Minujin’s Wild Textile Art at 80

In 2013, Argentinian artist Marta Minujin celebrated her 70th birthday by ‘marrying’ art. She staged a huge wedding party at the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA), during which she was carried around in a horse drawn carriage wearing a lavish white dress. It is a fitting introduction to Minujin’s madcap, eccentric world, in which art is all about irreverence, celebration, and the creative exchange of ideas. Fabric has been a key aspect of these thought processes throughout her decades long career, and her trademark clashing, colourful stripes have adorned a rich playground of soft sculptures, as well as the vivid jumpsuits she wears so often they have become her signature style.

Minujin was born in 1943 to a Russian-Jewish family in Buenos Aires. Her father worked as a tailor, diversifying into uniforms, where he made his fortune, thus cementing in Minujin a lifelong fascination with fabric. From a young age, she knew she wanted to become an artist, later recalling in an interview, “I was always married to art. I decided to be an artist when I was 10 years old.” She trained as an artist in Buenos Aires, before beginning to experiment with how mattresses could be transformed into works of art. “Half your life takes place on a mattress,” she recently told Rebecca Shaykin, associate curator at the Jewish Museum in New York, “You are born, you die, you make love, you can get killed on the mattress.”

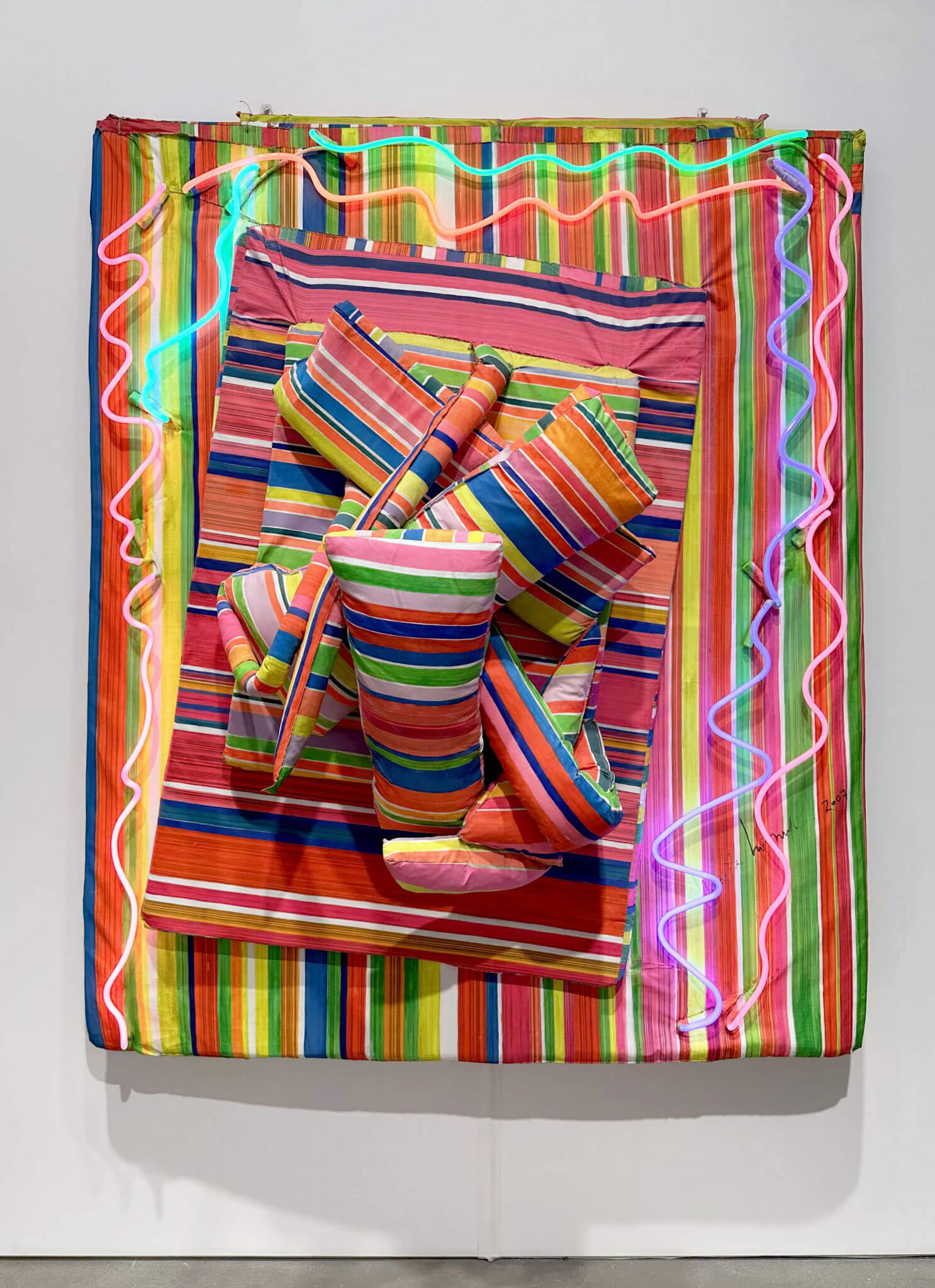

During the early 1960s, Minujin trained in Paris, and befriended many of the leading new realist artists including Nikki de Saint Phalle, Christo, and Jean Tinguely. Like them, she searched out everyday materials that could be reconfigured into artworks – which in her case involved scouring the dumpsters of Parisian hospitals for blankets and mattresses to create her trademark Colchones (Soft Sculptures). The artist’s first immersive, room-sized environment was Chambre d’Amour (The Room of Love), in which an entire room was padded with mattresses to create a fully immersive, softly insulated space. In the following years she expanded into carefully sewn, mattress-like sculptures made from vividly striped, hand-painted patterns, stitching together heaped piles of cushioned shapes to create oddly biomorphic, tactile objects resembling embracing bodies.

In the mid-1960s Minujin relocated to New York, befriending the city’s leading Pop artists including Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein, and it is clear to see a rebellious Pop sensibility in many of her most colourful soft sculptures. In the years that followed she leaned more heavily towards performance and happenings while living predominantly in Argentina, staging ephemeral, politicised events and experiences ranging from a Statue of Liberty replica made of strawberries for visitors to gradually eat (La Estatua de la Libertad de Fruitillas), to El Partenon de Los Libros, a recreation of Argentina’s Athenian temple made from 20,000 books once banned by the military junta, which visitors dismantled by taking away the books one by one.

In the mid-aughts, Minujin returned to making soft sculptures with a renewed vigour, as she explains, “I started with mattresses in the sixties, but then I stopped for 40 years, and then I started again in 2007. I went back to my roots.” In the colossal sculpture Conseptos Entrelazados (Intertwined Concepts), made between 2019 and 2022, a wild and carefree jumble of stitched soft forms in clashing striped patterns come together to create a teeming mass of abstract energy. As with so many of her soft sculptures, she deftly balances the raw, and often inelegant, intimacy of human touch with the soft tactility of mattresses that so often support it. “I was trying to create a world that was colourful, carefree, fun,” says Minujin.

Yet Minujin’s world is not all fun and games – she has often alluded to darker themes within her soft sculptures, such as Para Hacer el Amor Inadvertidamente (For Making Love Inconspicuously) 2010. In this work of art Minujin deliberately leaves rough, hand-made elements on show, including fading, peeling paint on the fabric surface, and forms hung suspended so that deliberately droop and sag. She thereby highlights the fragility beneath the human condition, creating a modern-day memento mori that seems to emphasis living life to the fullest, much like she does, while we still can.

Leave a comment