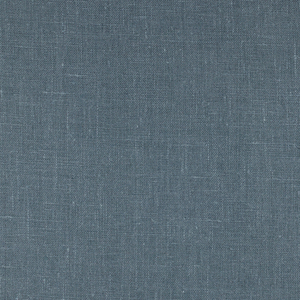

FS Colour Series: Laurel Leaf Inspired by Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Metallic Greens

Scottish artist and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh might be best remembered for his Art Nouveau architecture and furniture, but he was also a highly skilled painter who made distinctive, stylised paintings of flowers and landscapes filled with quiet, understated wonder. Cool, crisp shades of metallic green like Laurel Leaf were a recurring feature of his late career, observed watercolour landscapes, conveying atmospheric patches of enigmatic shadow falling across damp grass, worn buildings, or the uneven patina of craggy rocks.

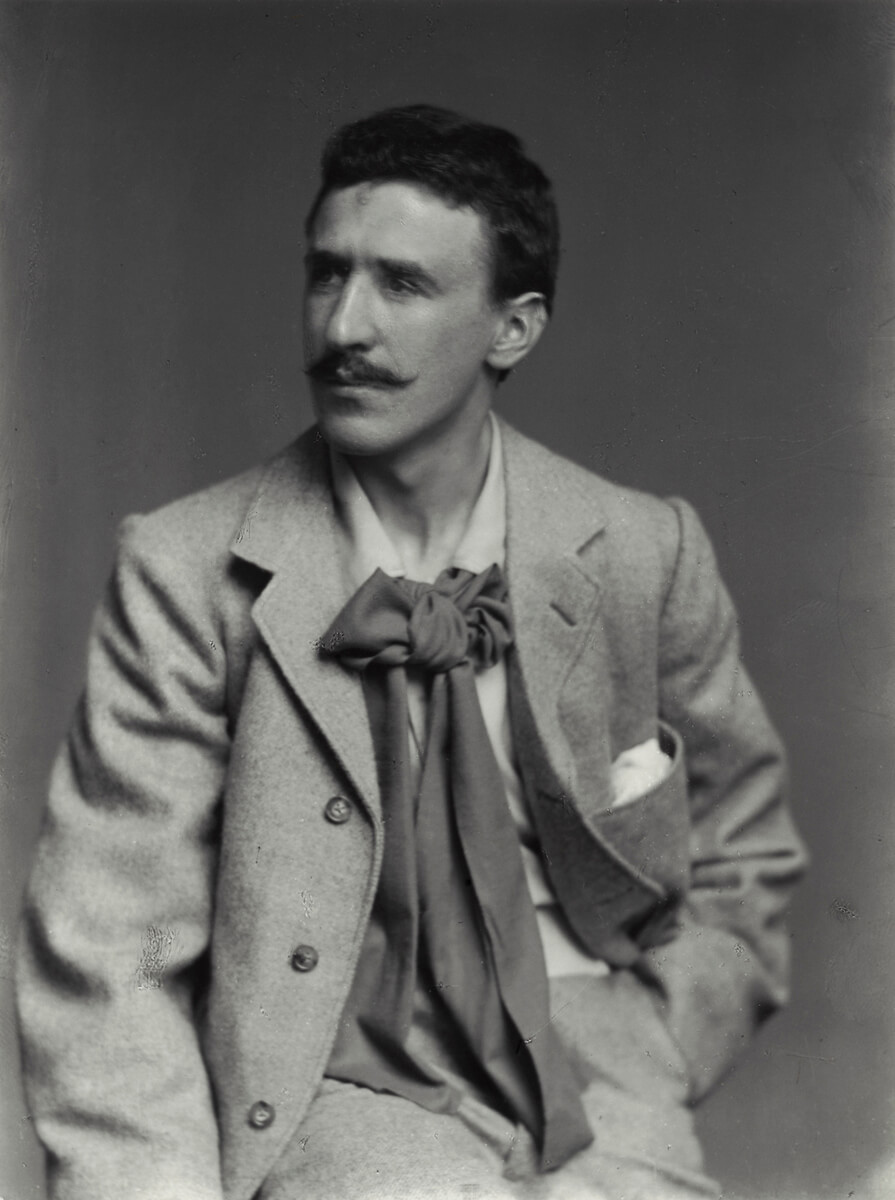

Born in 1868 in Glasgow, Charles Rennie Mackintosh spent the early part of his career earning a steady reputation as one of the most influential architects and furniture designers of his generation. Having lived in the UK for most of his adult life, Mackintosh moved to the South of France with his wife Margaret Macdonald in 1923, travelling throughout the area. From this point forth Mackintosh spent hours out of doors painting the surrounding landscape in watercolour with great enthusiasm, indulging in the sharp, fine details and linear contours of uneven rocks and rustic houses scattered throughout the town and surrounding countryside.

His paintings demonstrate Mackintosh’s unwavering ability to capture the underlying structures and patterns of nature, which he depicted with clearly defined, linear contours, and flat planes or shards of simple, minimal, and elegant colours. He wrote in a letter to a friend about an “insane aptitude for seeing green and putting it down here, there, and everywhere,” many of which were dark, shadowy, and ambient, capturing light falling across the land. We know that Mackintosh produced around 44 paintings during this prolific period of his life, which, although minimally successful during his lifetime, are now much prized and highly sought after collector’s items, capturing a rare, and brief moment towards the end of the artist’s life.

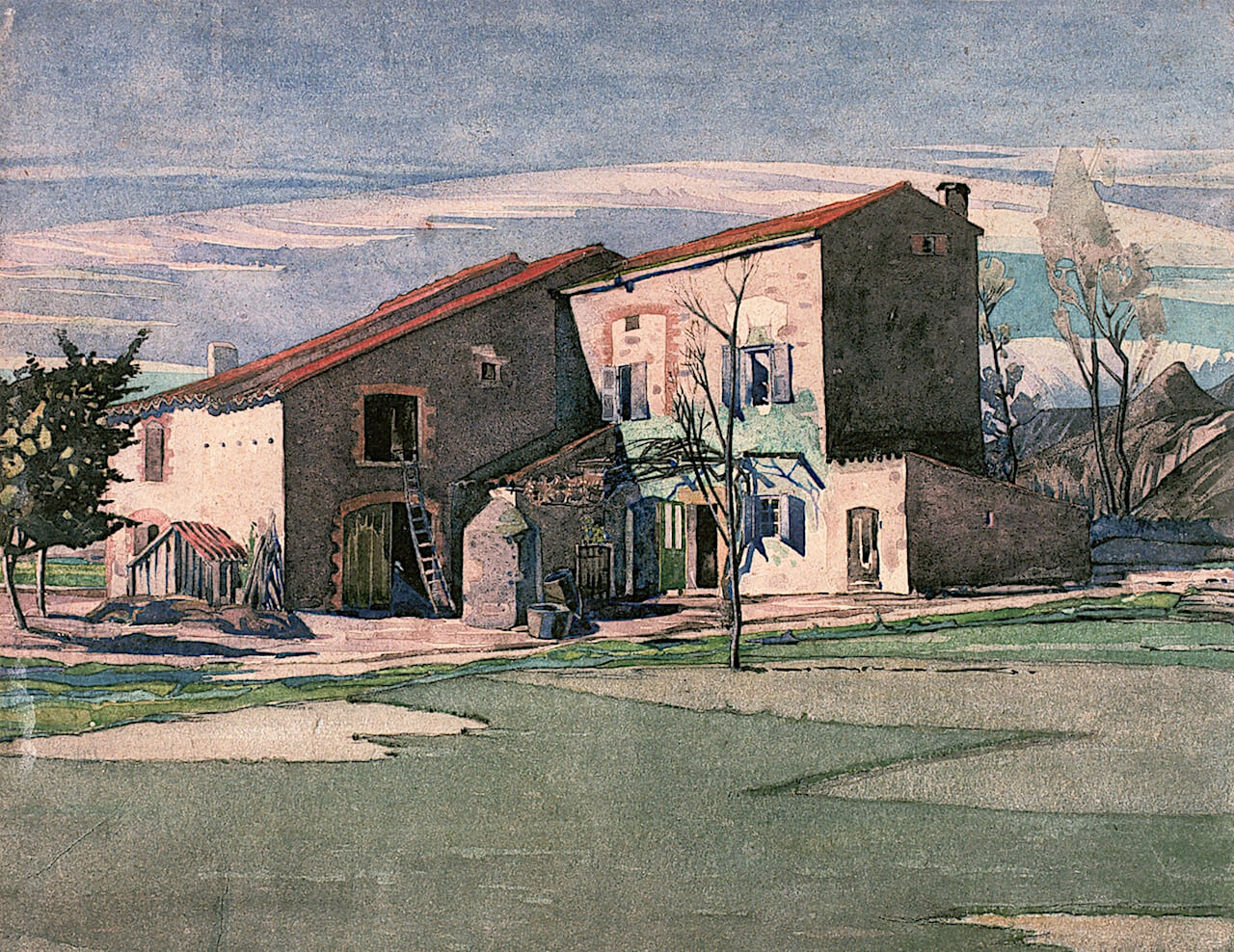

Blanc Ontoine, 1927 conveys the still, even light of a summer afternoon, with sun-baked, softly-toned grass forming a zig-zagged pattern across the foreground, and a near-cloudless sky casting razor-sharp, grey-green shadows onto the rustic French buildings set in the background. He contrasts these soft greens with slim shards of terracotta, streaked across the barely visible slanted roofs of the quiet, sleepy houses, that seem to carry with them the warmth of the sun.

The Village of La Llagonne, 1927, is brighter and clearer in tone, an aerial view looking out across a crowded cluster of buildings that open out into a patchworked landscape beyond. He contrasts the angular lines of the foreground architecture with the wayward, meandering contours of the farmlands, while a craggy cluster of rocks to the left, drawn with minutely careful precision, echoes the shapes and tones of the buildings. Throughout the scene, pale, luminous and golden tones are contrasted with metallic greens and greys – soft, subtle hues that convey the nuanced patinas of rock, stone, and grass cast into the cool shadows.

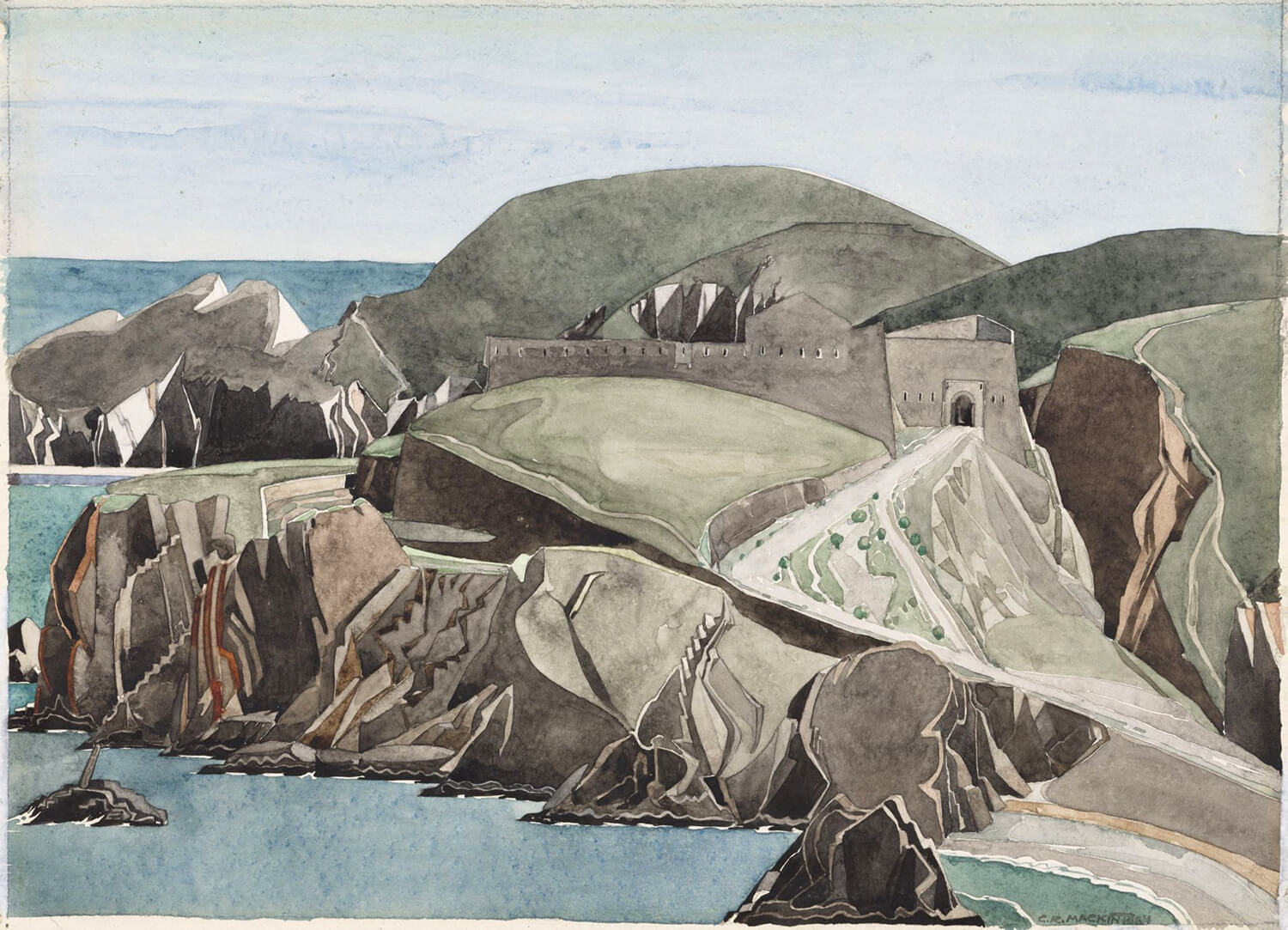

In Fetges, 1927, Mackintosh creates a greater fusion between the structure of the farmlands and the tangle of haphazard buildings that occupy it, echoing the same jagged, angular lines and crisp contours in each. Silvery strands of green and grey are interspersed throughout the buildings and the landscape, a point of sharp contrast against the vivid greens, yellows and oranges around them. He demonstrates his skill in rendering structure and form with an exacting, architect’s eye, capturing the rectilinear angles of the rocks and houses as they shift in and out of the light, and a believable depth of field as our eye travels across the jumbled foreground and off into the barren landscape beyond.

Leave a comment