Hilma af Klint: Seances and Spirits

Swedish artist Hilma af Klint is one of the 20th century art world’s best-kept secrets. An abstract painter of extraordinary talent and foresight, she pioneered a deeply spiritual strand of abstraction centering around Theosophy, spirits, seances, and the occult long before her male counterparts like Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Kasimir Malevich. Yet she kept her art hidden away for fear of ridicule, only agreeing on its release 20 years after her death in 1944. It wasn’t until the 1980s that her art began receiving critical attention, and it is only in recent years that her full archive has seen the light of day.

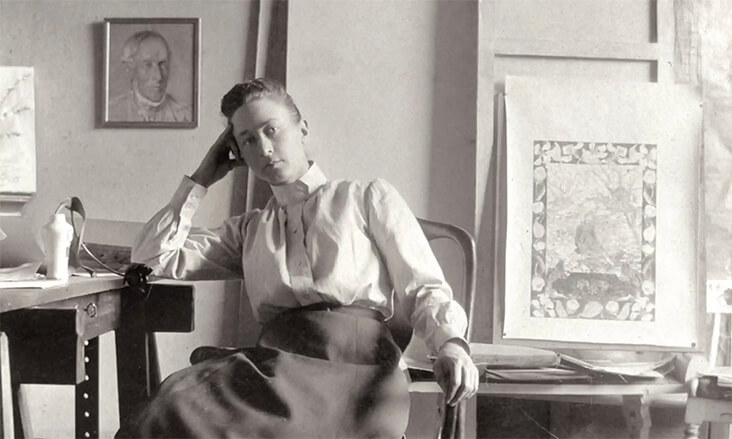

Born in 1862, Klint trained as an artist at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm, graduating in 1887. She set up a studio in the city next door to the Swedish Association of Painters, from where she began producing high-quality traditional landscapes, commissioned portraits, and botanical drawings. Such was her talent she was able to fully support herself as a commercial artist. In 1888, Klint joined the Swedish Theosophical Society, part of a widespread religious movement across Europe and the US which blended elements of Eastern and Western religion with elements of Greek mythology and the occult.

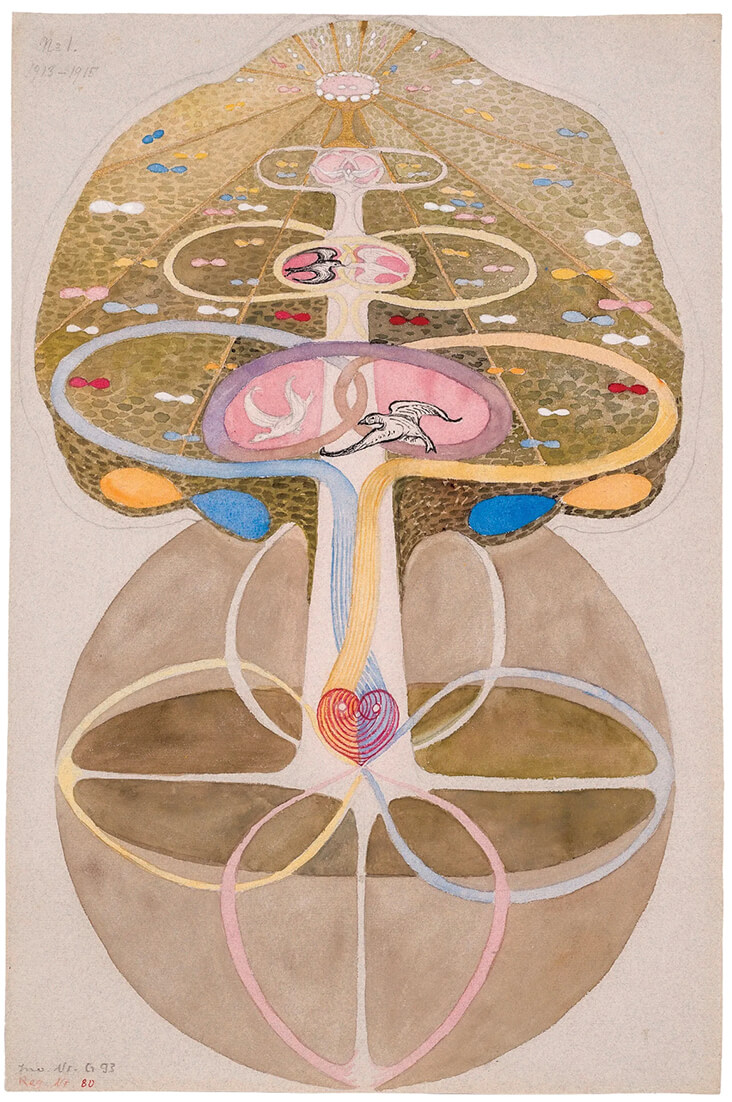

By the 1890s, Klint began incorporating elements of Theosophy into her art practice in private, while keeping up her public persona as a commercial artist. Klint was particularly drawn to the Theosophical notion of nature as a conduit that could lead towards the spiritual, and botanical shapes and forms were a recurrent theme in her mature art representing moments of transition between one world and another.

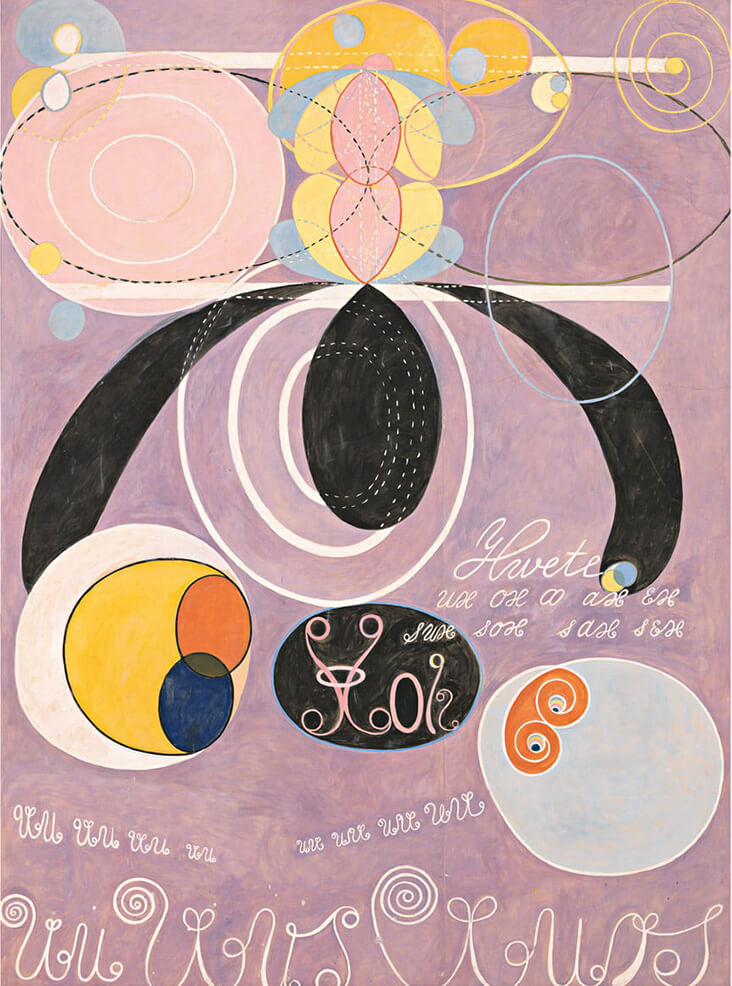

In 1897 Klint joined forces with a group of female artists and friends – Anna Cassel, Sigrid Hedman, and sisters Mathilda Nilsson and Cornelia Cederberg – who called themselves ‘The Five’, or ‘De Fem’. Together they began meeting in secret in one another’s houses, where they would regularly conduct seances, attempting to commune with spirits and mystic beings that they called ‘High Masters.’ These seances were followed by free-flowing drawing and writing sessions to release the imagery brought to them from beyond the real world. Remarkably, the pioneering practices of these five female artists predates the similar automatism of the French Surrealists by nearly 20 years.

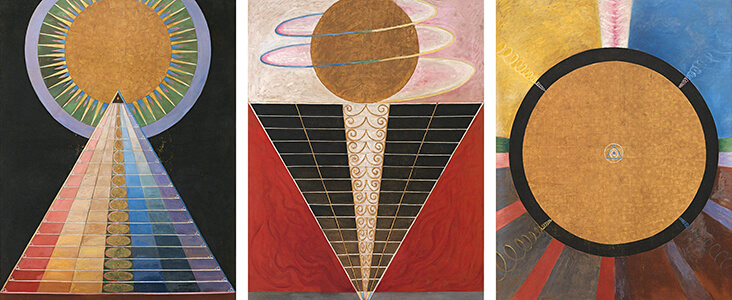

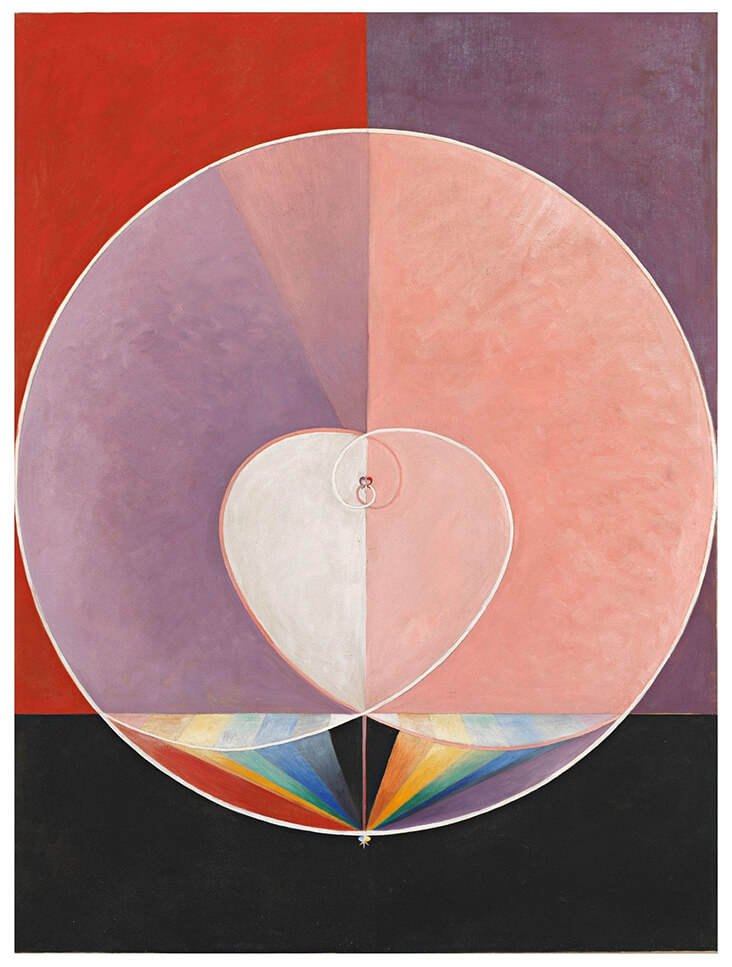

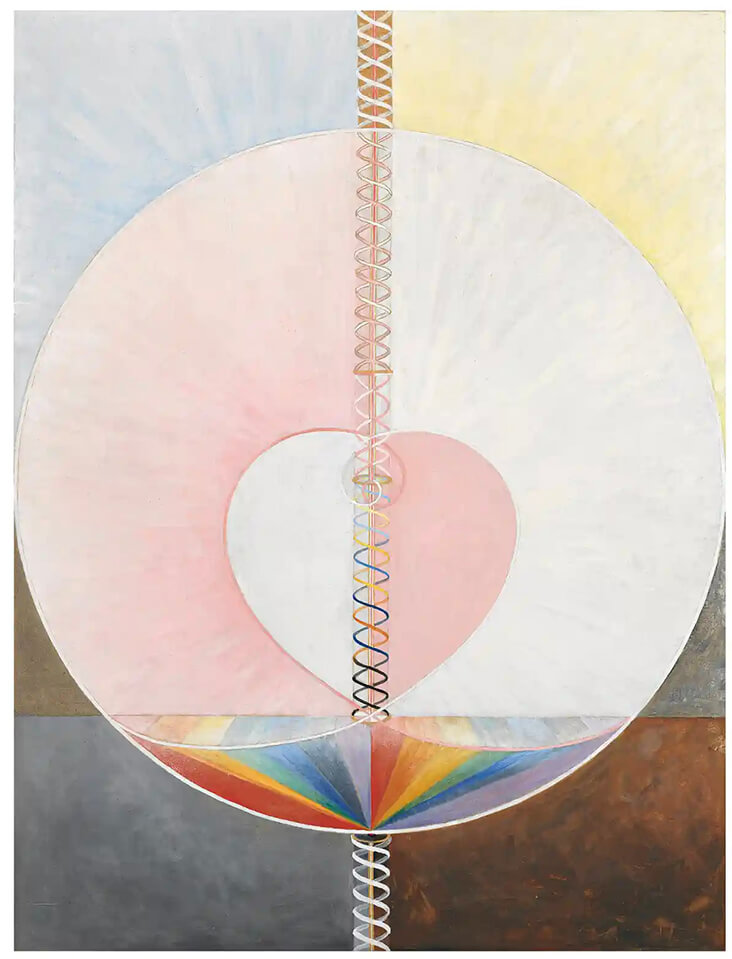

In 1905 Klint experienced an epiphany during a particular séance. She wrote in a notebook that a spirit named Amaliel had given her a personal commission to create a large body of work as a gateway into unseen realms. This moment of awakening led Klint to create what is now recognised as her most significant body of work, titled Paintings for the Temple. From 1906 to 1915 Klint was extraordinarily prolific, producing 193 paintings for this series, which she divided into various thematic sub-groups. She wrote in a personal notebook, “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

Among themes explored in the series are the discovery of electromagnetic waves, the teachings of Rudolf Steiner, a friend and mentor to Klint, and the connection between animals, nature, and metaphysical realms. Throughout this incredible series Klint painted in a surprisingly diverse range of scales, sizes and themes, producing an extraordinary body of work that merged abstract geometric and biomorphic forms, a private, coded symbolism, and brilliantly bold colours that hum and vibrate with sonorous musicality. Klint envisioned one day showcasing her series in a spiral temple, taking viewers on an intoxicating journey higher and higher towards heaven. Whether she thought this would be a real temple or one in another dimension is unknown, but earlier this year an art group called Acute Art created a virtual reality site where Klint’s images appear to be hung in a swirling temple, thus finally realising her vision.

In her later years, Klint continued to explore the same breakthrough language of this series up until her death in 1944, but she kept this radical art hidden away, working in isolation without a connection to the wider art world. Since the 1980s, the reputation of Klint’s art has continued to grow and grow. Thanks to recent retrospective exhibitions in high profile spaces including London’s Serpentine Gallery and New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Klint is now achieving a level of international recognition that she never would have expected, but completely deserves.

5 Comments

t a

messing with the occult leads to all kinds of spiritual bondage, dangerous territory.

Kate Renwick

Thank you for bringing this to our attention. Truly amazing art and person.

Thank you for all of your articles introducing us to artists we might not know of.

Michelle French

The first time I heard of Hilma af Kint was at the time of the Serpentine show. It was amazing and gave me chill bumps. Her work is so fresh and inspiring. Several times I thought “I wish I had painted that.” Just looking at her art online or the books I have makes me want to go to the studio and paint huge paintings.

I suppose the Guggenheim show did present her work in a “spiral temple” though who could have imagined it at the time.

I have snickered that the Guggenheim represents itself as the first show to a world audience.

Erika Jean

What a talented and intriguing artist! I’ve read about her before, but not with this much detail. Thank you!

Vicki Lang

What a beautiful spirit and person. Her paintings are fantastic and move the spirit when viewed. Thank you for bring such a lovely person to the fore front.