Everyone is an Artist: Kunstakademie Dusseldorf

Germany’s Kunstakademie Dusseldorf is widely recognised as one of the most radical art schools in the world. The 1960s and 1970s were a particularly profound period for the academy, when ground-breaking teaching methods gave rise to progressive new forms of performance art, painting and photography. Since then, the school has remained a respected centre for educational innovation and experimentation. One of the school’s defining principles is the emphasis on the freedom and autonomy of the individual student, along with an awareness of how global politics can inform art practice. These influences show in the school’s extensive alumni, who include Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, Anselm Kiefer, Blinky Palermo and Candida Hofer.

Kunstakademie Dusseldorf was founded in 1773 in the relatively small German city of Dusseldorf, and it quickly became recognised across Germany as a leading art institution. In the 1960s, the school hit the international stage, and this was largely because of the school’s outstanding roster of teaching staff. One of the school’s most influential and boundary-pushing teachers was the legendary performance artist and ‘social sculptor’ Joseph Beuys, who saw teaching as an extension of his art practice. He even claimed, “To be a teacher is my greatest work of art.”

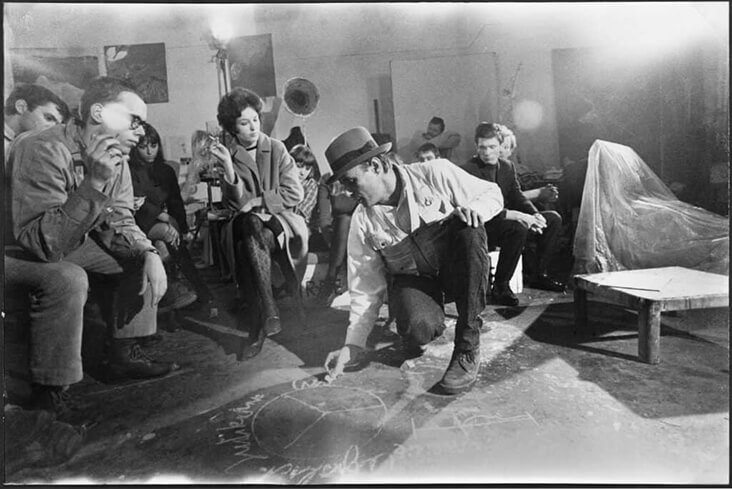

Beuys was appointed as professor of monumental sculpture at the Kunstakademie in 1961, but his teaching methods moved far beyond sculpture, incorporating elements of performance, poetry, installation and drawing. In fact, drawing was at the core of Beuys’ teaching, because he believed it rooted each and every student to their own autonomous way of seeing and understanding the world. He told his students, “You mustn’t look how the others draw, but must discover your own way of drawing.” He also organised ‘ring discussions’ in which students would gather in a circle and have active discussions about world politics and how it could inform their artistic practice.

Over time, Beuys’ teaching methods became increasingly erratic and experimental. He declared “everyone is an artist,” and admitted any willing students into his lessons, even if they had failed the entrance exams. Beuys encouraged his students to see their daily lives as a continuous work of art and argued that simple acts like posting a letter could be as much a work of art as a hand-crafted object. He even founded a political party with his students, called the German Student Party. Such was his popularity, Beuys eventually attracted over 120 students to his class, many of whom had been rejected from the art school. This move was controversial enough to have Beuys dismissed in 1972, but by now he had already left a lasting impact on his students. Among them were the Capital Realists Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke, who went on to become internationally successful in the decades that followed.

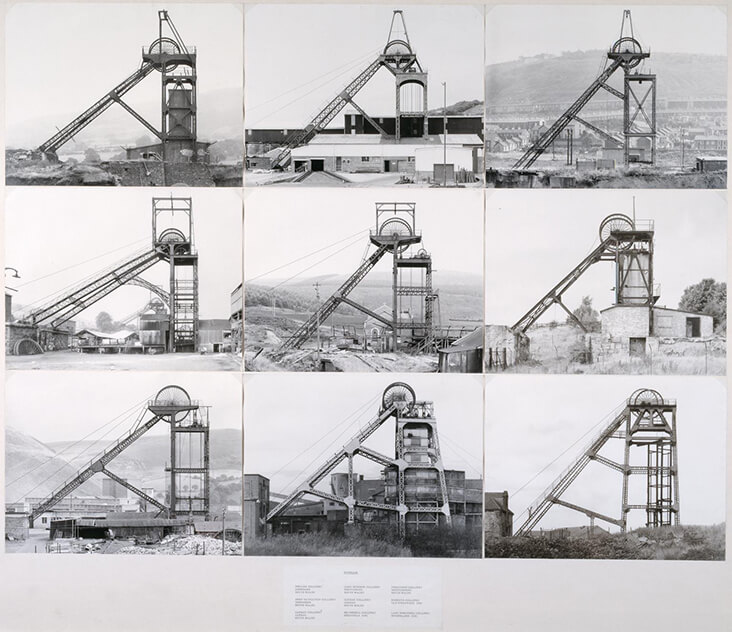

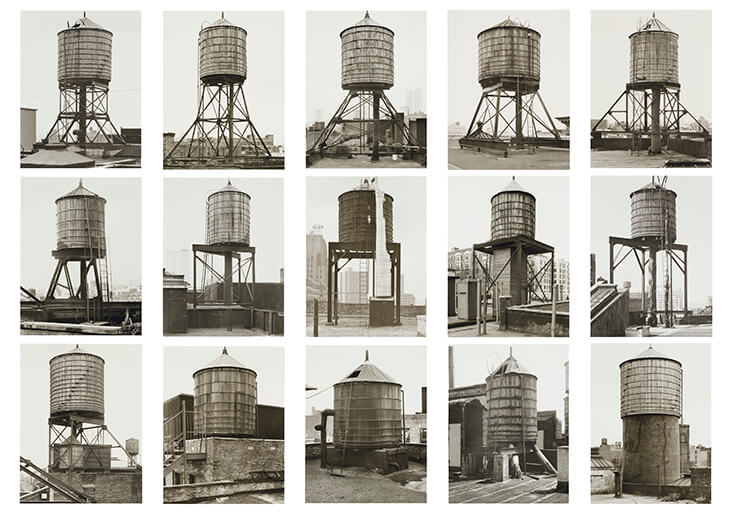

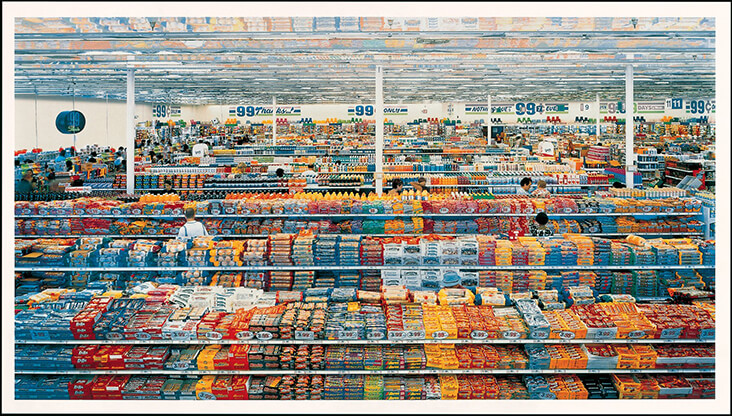

In the 1970s, the pioneering husband and wife photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher joined the teaching faculty at Kunstakademie Dusseldorf. Their influence was nothing short of monumental. The Bechers’ own brooding, atmospheric photographs documented industrial relics on the brink of destruction, brought together as a series of hypnotic, repetitive grids. These serial artworks merged the boundaries between photography, conceptual art and even sculpture in an entirely new and novel way. As teachers, the Bechers encouraged their students to take an observational, socially engaged approach to photography, and to find ways of relating their photographs to their own humble, ordinary, and individual experiences out in the real world. Today, a core group of the Bechers’ former students from the 1970s and 1980s, including Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth, are world-renowned, and known collectively as the Dusseldorf School of Photography. Meanwhile, the conceptual approach that the Bechers pioneered continues to dominate the nature of photography today.

Principles of the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf, including Markus Lupertz, Tony Cragg and most recently, Rita McBride, have tried to maintain the school’s reputation for fostering experimental freedom and artistic autonomy, even when faced with governmental challenges to standardize higher education into a school-like structure. The art academy has continued to understand how vital this spirit of individual freedom has been in securing success in so many of their former students. On their website, they write, quite simply, “Artistic activity unfolds in the spirit of total freedom in art.”

Leave a comment