Fabric in Ukiyo-e Art: The Utagawa School

The Utagawa School was one the most successful periods in the history of Japanese ukiyo-e art, lasting from the late 18th to the late 19th century. Under the leadership of master printmaker Utagawa Toyoharu, the school revolutionised Japanese woodblock printing, discovering new techniques that allowed them to work quickly and efficiently, creating a huge array of affordable images they could sell widely across the city of Edo (now Tokyo) and beyond. These prints were radical and modern in design, making a departure from ancient Japanese traditions with elements of perspective, stylised line, busy designs and dazzlingly bold costumes. Fabric, as we will see, was vitally important, aiding in the storytelling potential of these progressive ukiyo-e prints.

Utagawa Toyoharu (1735-1814) was born in Toyooka in the Tajima. He studied art in Kyoto, before moving on to train in Edo with Toriyama Sekien. It was here that he established his successful woodblock print workshop. Though his subjects were varied and diverse, he became particularly well-known for his pioneering prints featuring two particular subject areas: bijin-ga (beautiful women) and uki-e (perspective pictures).

Utagawa’s bijin-ga prints were particularly focussed on the fashions and customs of beautiful Japanese women, which he portrayed with his own distinctively stylised use of slim lines and decorative patterns. Many were based on real women seen in the ‘ukiyo-e,’ or ‘floating world’ of Edo, the bustling street and theatre district which was expanding in popularity – a typical example is his elegant print, The Noda Jewel River in Mutsu Province, 1800, which features a family group whose neutral, organically printed clothing merges with the surrounding landscape.

Some women who featured in Utagawa’s prints were even high-class courtesans, and Utagawa portrayed their clothing with such sensuous beauty that their dress sense was adopted by women from all walks of life across Japan. This celebration of the erotic possibilities of fabric, (as opposed to the nude female form which dominated Western art history) can be seen in Utagawa’s print, Courtesan and her Attendant under a Cherry Tree from the early 19th century, where a high-ranking courtesan wears dashing red underlayers and a stunning black surcoat adorned with peacock feather motifs, an ensemble mimicked by her smaller attendant.

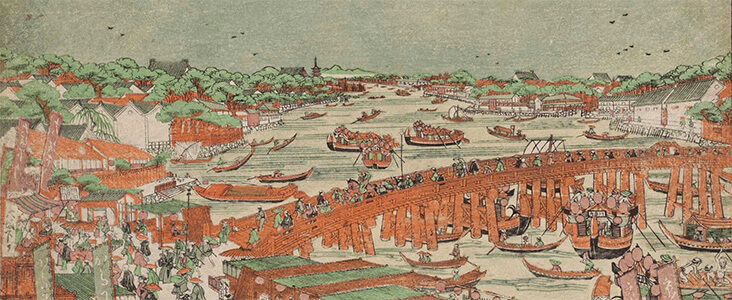

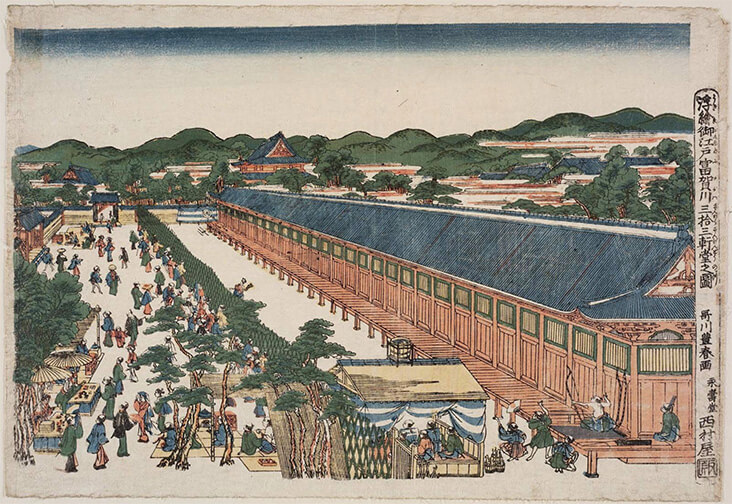

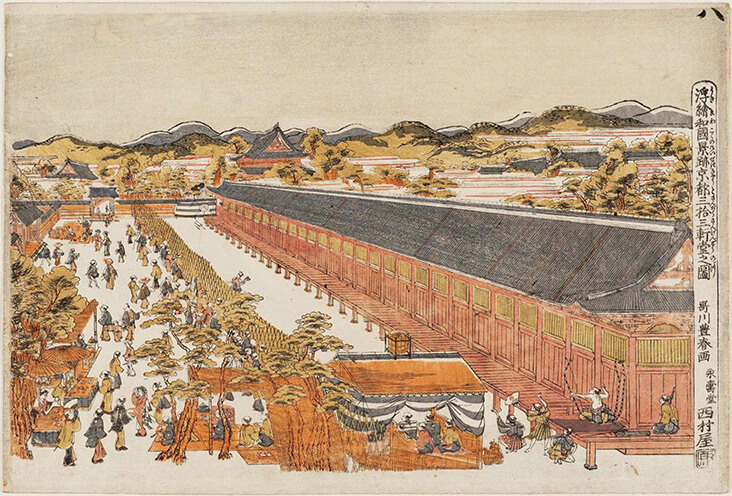

Utagawa’s uki-e (perspective picture) prints were strongly influenced by the single point perspective of Western and Chinese art, introducing new levels of depth and space into the flattened stylisation associated with traditional Japanese art. Although Utagawa’s uki-e prints were often wide-open vistas and busy street scenes featuring architectural detail, the artist still explored how fabric and costume could enhance depth of space by suggesting bristling bodily movement and curving organic forms. We see this clearly in the bustling, strikingly complex prints Perspective Picture of the Sanjusangendo at Fukagawa in Edo and The Sanjûsangendô in Kyoto, both from the late 18th century.

As was customary in Japanese tradition, Utagawa’s most ardent followers adopted the ‘Utagawa’ name and carried it forward for a new generation, copying and advancing on the style of their master. Utagawa’s most prominent pupil was Utagawa Toyokuni I, who took over the Utagawa School following the death of his predecessor. His prints were similar in style to his master but even more daring and striking in colour, texture and design, as seen in his adventurous Courtesan as Botanka Shohaku, featuring two women adorned in layers and layers of richly decorated fabric, featuring ornate floral patterns that emphasise their femininity. Toyokuni I was profoundly influential as leader of the Ushagawa School, leading his group of followers to become the most popular and successful phase of Japanese woodblock printing so far. The school’s influence was far ranging, not just in Japan but into the West, influencing a whole host of artists including Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, whose stylised Japonisme is still shaping the nature of the world’s art today.

Leave a comment