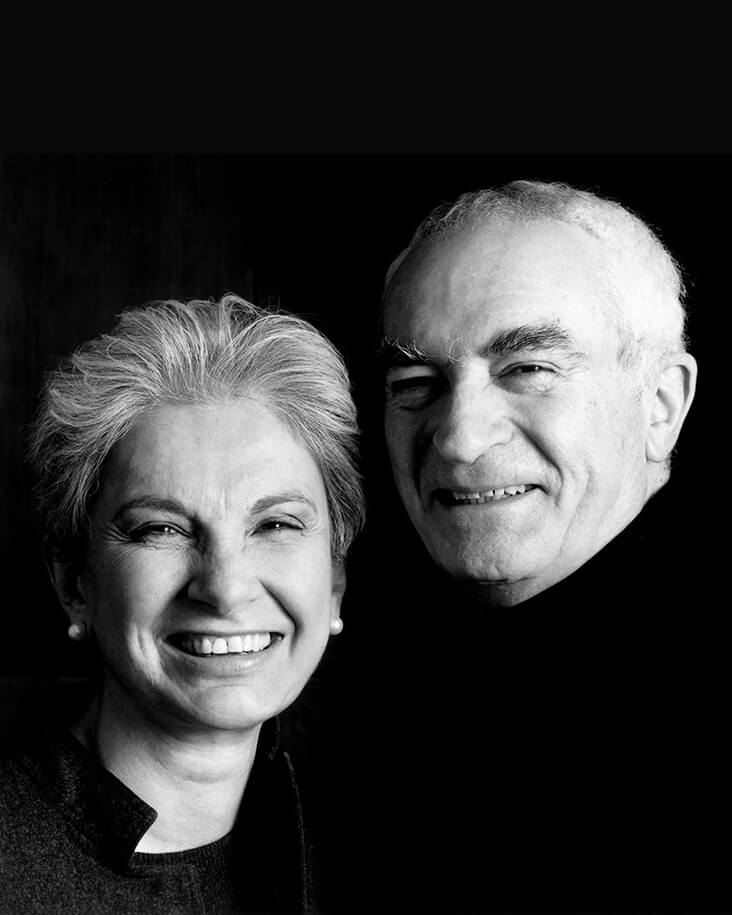

The Italian Touch: Massimo and Lella Vignelli

Italian husband-and-wife team Massimo and Lella Vignelli made a remarkable contribution to late 20th century design, ushering in a new brand of elegance, simplicity and order. Both trained as architects but their legacy is far more extensive, spanning silverware, bags, watches, furniture and typography. “If you can design one thing, you can design everything,” they famously wrote, prompting critic Paul Goldenberg to call them “total designers.” But perhaps most memorably, they are credited today with introducing a distinctly Italian, classical touch to the American market, strengthening the relationship between the United States and Italy.

Massimo Vignelli trained first as an artist in Milan before studying Architecture in Milan and Venice in the early 1950s. Lella (born Elena Vall) also trained as an architect in Venice and later earned a scholarship to study at MIT’s School of Architecture. The couple first met at an architecture convention, and in 1957 they married. The first three years of their life together were spent living in the United States, where Lella worked for the Architectural firm Skismore, Owings and Merrill and Massimo completed a study fellowship.

In 1960 the couple relocated to Milan, joining forces to establish the Massimo and Lella Vignelli Office of Design and Architecture. From the outset their approach was diverse, encompassing interiors, furniture, exhibition and product design. One of the couple’s best-known early works is the Saratoga Sofa, produced by the radical furniture company Poltronova in 1964. Its understated elegance, contrasting glossy polyester chassis with soft leather seating came to typify the couple’s subtle yet powerful aesthetic.

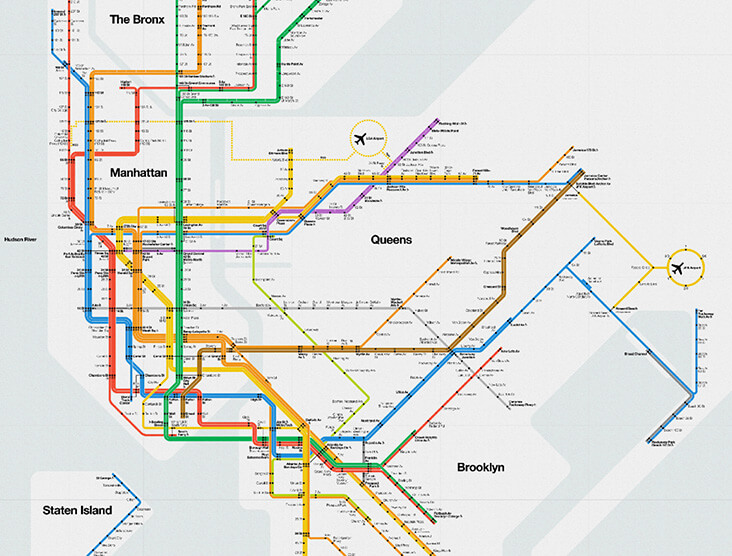

In 1965 the Vignelli’s decided to return to the United States, where they founded the design and marketing company Unimark alongside their friends Bob Noorda and Ralph Eckerstrom. It was through this platform that some of the couple’s most iconic motifs were created, including the logo for the American airlines and the signage for New York City’s subway system. Unimark’s increasing focus on marketing would eventually drive Lella and Massimo out; by 1971 they had established Vignelli Associates, a new company with a wider design outlook.

Both Lella and Massimo were tirelessly ambitious for Vignelli Associates and their dedication led to the company’s international success throughout the 1970s. A central office was set up in New York City, with further branches later opening in Milan and Paris. Some of the company’s most successful and prominent projects of the era included the interiors of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, the redesign of St Peter’s Lutheran Church in Manhattan and the map of New York’s subway system, which built upon their earlier signage with Unimark. From the 1970s to the 1990s the Vignellis also worked closely to create some of the world’s best-known furniture pieces, including the Handkerchief Chair, 1982, the Wagneriana Floor Lamp, 1982 and the Paperclip Table, 1994.

Throughout this prolific period, the couple emphasised striking simplicity and minimalism, but their designs also have a quirky playfulness, combining traditional materials such as marble, leather and polished wood with experimental angular and curvaceous forms. This quietly rebellious streak echoes the subtle, tongue-in-cheek spirit of mid-century modernism.

As a couple the pair each played to their strengths – Lella took on furniture, exhibition and interior design, while Massimo worked on typography and layouts, although they came together before finalising just about everything they produced. Even so, Lella was rarely acknowledged as an equal partner in the company. Massimo was said to be so incensed by this glaring inequality that he would sometimes throw away any magazine or publication that failed to include her name alongside his. In 2013, just a year before his death, Massimo produced the book Designed by: Lella Vignelli, dedicated to her lifelong work and the many unacknowledged contributions she made to the design industry. The book also highlighted the problem with what Massimo called “macho attitudes” that have written out women’s roles in the many husband-and-wife teams of the design world. He wrote, “For decades, the collaborative role of women as architects or designers working with their husbands or partners has been under appreciated.…Lella and I were affected by these standing mores early in our careers. It is why we purposely built the notion of the two of us as a brand, but it took time for the others to see and understand this.”

One Comment

Maureen Christensen

Interesting article, thank you…