Modern Folklore: Diaghilev and Larionov

Russian radical Mikhail Larionov is perhaps best-known as the rebellious young artist who galvanised 20th century abstraction in Russia. But in his later years, he went through a dramatic transformation, reinventing himself as a set and costume designer for the European stage. It was Larionov’s close friendship with Ballets Russes director Sergei Diaghilev that made this unlikely, cross-continent transition possible. Larionov and Diaghilev had much in common; both were Russian emigres living in Paris, and both shared a mutual fascination with Russian folklore and the European avant-garde. Together, they fused Russian history with the experimental languages of modernity, reinventing a new brand of Russian identity.

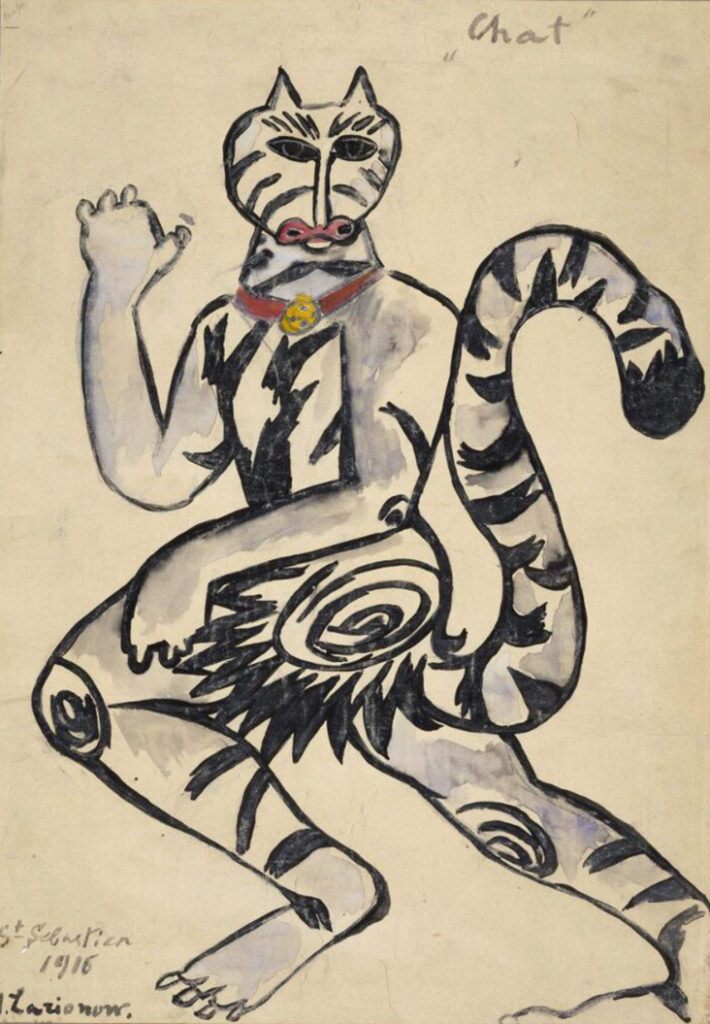

Mikhail Larionov design for the costume of the cat in the ballet Kikimora in the Ballets Russes production of Contes Russes (Children’s Tales), 1916, V&A Museum, London

Larionov began working as a set and costume designer with Diaghilev in Paris in 1915. Diaghilev had long been an admirer of Larionov’s paintings, observing with fascination how he fused Russian history and heritage with the angular shards and faceted forms of Cubo-Futurism. But it was Larionov’s interest in the visual and cultural traditions of Russian folklore and peasantry that really captured Diaghilev’s imagination. Taking inspiration from Larionov’s ideas, Diaghilev sought out ways to instil elements of Russian folklore and what he called Larionov’s “Russian essence” into his ballet productions, through storylines, music and choreography. Ballets Russes choreographer Leonide Massine, who worked closely alongside Diaghilev and Larionov observed how “it was thanks to Larionov,” that Diaghilev began introducing Russian folk dance into the ballet, noting how “he first came to understand the true nature of these old peasant dance rituals.”

Many of the Ballets Russes productions that Larionov designed sets and costumes for were lifted from Russian folk stories. Soleil de Minuit (Midnight Sun), 1915, took its narrative from a series of Russian folk legends, with the choreography of Massine and music by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Diaghilev hoped to create what he called a “modernised folklore form” with the ballet production. Larionov’s response to this theme was to merge the vivid, dazzling colours of Russian lubok prints with the experimental playfulness of Futurism, exploring how moving props, angular face-make-up and jarring, disjointed forms could enliven the theatrical experience. In the centre of his stage set was a huge, rotating sun, against a midnight blue backdrop, recalling the colours of ancient Russian solar symbolism. Circular sun shapes echoed in the dancers’ costumes alongside rich jewel tones in contrasting abstract patterns.

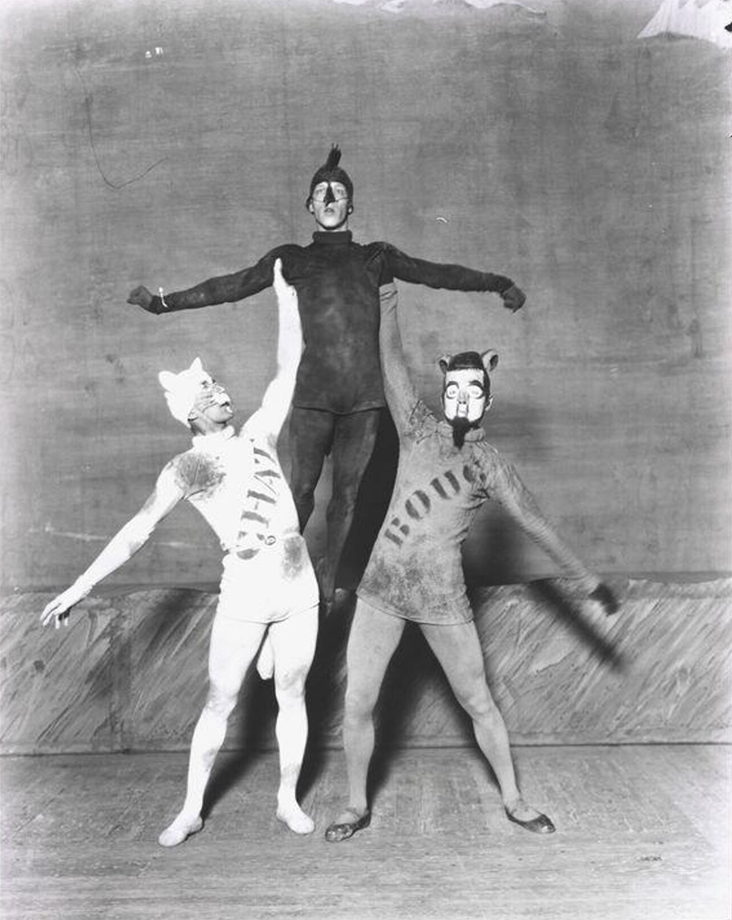

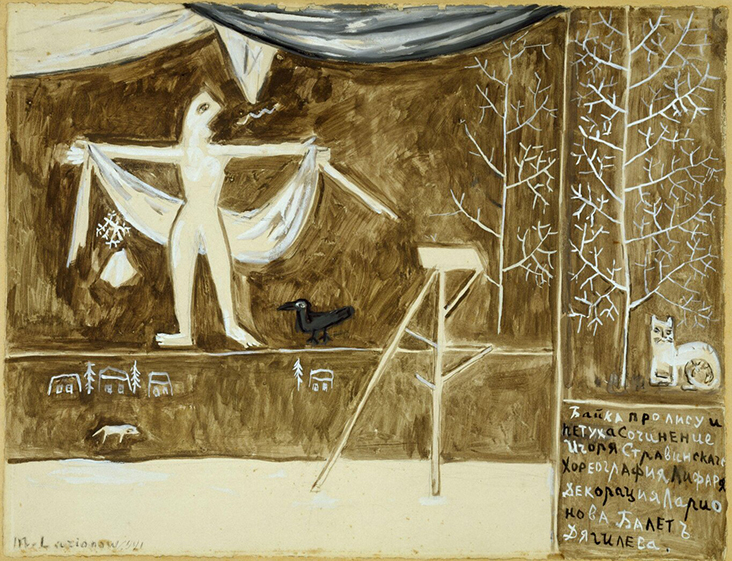

In Contes Russes (Children’s Tales), 1917, another suite of popular Russian folk tales were brought alive through the Ballets Russes and a magical score by Liadov Anatoly. Larionov designed sets, costumes and his own choreography this time, taking an experimental approach with dancers disguised as sets that suddenly sprang to life as swaying flowers, moving huts and living forests. In his set design for Baba Yaga’s forest, Larionov brought in a series of intersecting diagonals and varicoloured arcs, recalling the splintered language of his earlier Rayonist art, and the dynamic movement of Futurist painting.

Costume for a Soldier in Larionov and Slavinsky’s ballet Chout designed by Mikhail Larionov, Diaghilev Ballet, 1921

The experimental ballet Chout (The Buffoon), 1921 was based on another Russian folk tale, this time one of duplicity and disguise, with the music of Prokofiev and choreography a team effort between Larionov and Thadee Slavinsky. Larionov demonstrated his growing confidence with the experimental art of ballet design with vividly coloured Cubist-style scenery featuring bold graphics and intense, eye-catching colours. The outlines of Larionov’s costumes were based on traditional Russian peasant clothing, but he filtered them through his modernist European eye, re-imagining their shapes and forms with angular shapes, patterns and colours arranged into lively, haphazard and deconstructed forms. Some costumes were even made to extend outwards like stage props with stiffened buckram, felt, rubberised cloth and heavy cane structures; they constricted dancers’ movements to such a degree that some feared they might not be able to perform the choreography on stage.

Following Diaghilev’s untimely death in 1929, Larionov continued to work on a wide array of theatre projects including ballet and opera productions. But it was arguably his work alongside Diaghilev that made the biggest splash, combining a distinctly Russian spirit with the wild and unchartered freedom of modernity.

4 Comments

Cynthia Vournas

Thank you for this very interesting article,

Rosie Lesso

Great to hear you enjoyed it!

Elizabeth Horst

Thank you for this succinct history lesson. Its great to think about how the arts interconnect, and especially in clothing construction, how we can look to the stage and to costuming for modern inspiration.

Lately I’ve been wanting to do some creative color blocking and this article has inspired me to ‘dance’ right into it.

Rosie Lesso

Thanks for the comment – that’s wonderful to hear!