A World of Escapist Wonder: Diaghilev and Bakst

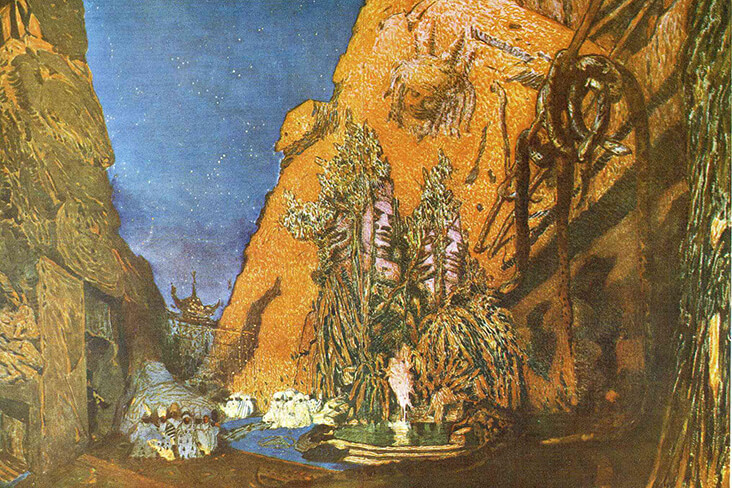

Scenery design by Leon Bakst for Scheherazade, produced in 1910 by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes.

Sergei Diaghilev and Leon Bakst were two fellow Russians of monumental talent, whose partnership became one of the most radical of the early 20th century. Leon Bakst was the first artist that Diaghilev would work with on his Ballets Russes in Paris, and together they transformed the theatrical stage into a living canvas, revolutionising ballet into a site for avant-garde experimentation. Their collaboration proved monumentally successful, stunning Parisian audiences with a mystical world of far-flung distant places filled with ornate decor, from the tall columns of Ancient Greece and Egypt to the magical colours of the Orient. Bakst held audiences in the palm of his hand, transporting them into a mystical, entrancing world of escapist wonder that was like nothing anyone had seen before.

Costumes for brigands in Fokine’s ballet Daphnis and Chloé, designed by Léon Bakst, 1912. © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Trained as a painter in St Petersburg, Bakst turned his hand to theatre set design in the early 1900s in Russia. Bakst moved to Paris in 1909 to begin working for Diaghilev’s new Ballets Russes, which was still in its infancy. Diaghilev’s idea was to completely transform ballet from a traditional site of pink tutus, flat backdrops and conventional choreography into a realm of creative exploration, with the help of Russian choreographer Michel Fokine, dancer Vaslav Nijinksy and the composer Igor Stravinsky. Bakst, too, played a vital role in making the dream a reality.

Costume for Zobeide in Scheherazade, designed by Léon Bakst, about 1911, Europe. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

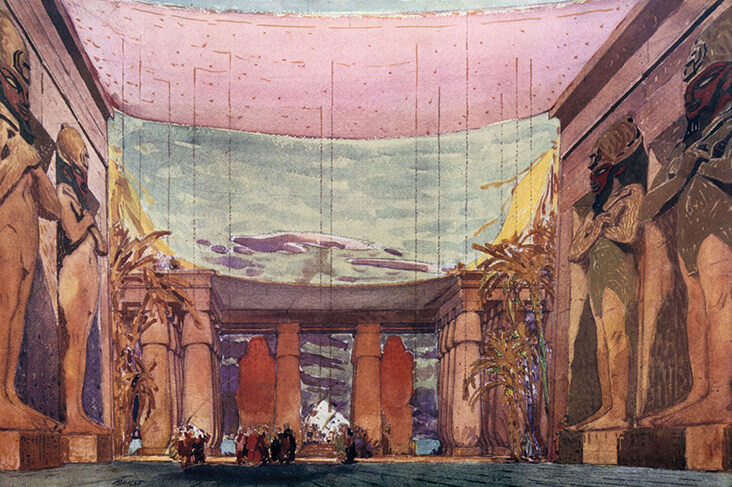

Bakst had a particular gift for capturing the spirit of place, and his designs for the Ballets Russes first season production of Cleopatre, 1909 captured the essence of Ancient Egypt, with dramatic backdrops filled with monumental statues and cavernous temples that seem to fade far into the distance. His costumes were equally as atmospheric, featuring stunning bejewelled embroidery, deep, entrancing colours, and swirling, linear designs that followed the contours of the body as it moved through space. Gone were the traditions of the past and audiences were dazzled by the exotic beauty of the new ballet. Bakst wrote, “It is goodbye to scenery designed by a painter blindly subjected to one part of the work, to costumes made by any old dressmaker who strikes a false and foreign note in the production; it is goodbye to the kind of acting, movements, false notes and that terrible, purely literary wealth of details which make modern theatrical production a collection of tiny impressions, without that unique simplicity which emanates from a true work of art”.

The ballet Scheherazade, 1910 was even more sensational – Bakst captured the magical eroticism and danger of the Arabian Middle Ages with violent slashes of colour and indulgent layers of beads and jewels that were dripping from his characters’ bodies. Such was the success of Bakst’s designs that he came to influence the nature of Parisian haute couture fashion – Russian poet of the era, Maximilian Voloshin noted how, “Bakst managed to grasp the elusive nerve of Paris, which is in charge of fashion. At the moment his influence affects all of Paris – from ladies’ dresses to art exhibitions.”

Bakst was particularly skilful at conveying mood through the colour and pattern of his costumes, noting how subtle nuanced differences in shades and tones could convey a change in tempo. “There are some reds which are triumphal”, he observed, “and there are reds which assassinate”. He was also acutely aware of the ornamentation of the Art Nouveau style, exploring how he could introduce its indulgent linear forms, floral shapes and intricate patterns to add depth of weight to his characters. He mixed elements of hand-dyed fabric with applique stitching, sequins, beads, metal studs, pearls and jewels to create stunning costumes now recognised as works of art in their own right.

The later ballet Daphnis et Chloe, 1912, was set in the depths of Ancient Greece, a love story that unfolded in amongst deeply atmospheric backdrops featuring tall painted trees and dusty temples. Costumes were brought up to date for the 20th century with an array of vivid colours and patterns; shepherds and shepherdesses wore earthy shades of yellow, brown, green and white adorned with naturalistic motifs such as stylised ram’s heads, while invading brigands were a stark contrast, dressed in jarring shades of purple or dark blue and aggressive checks and zig-zags.

Bakst and Diaghilev worked together less frequently as the years rolled on, with each moving in divergent directions – Diaghilev was increasingly involved with artists practicing avant-garde styles of abstraction, while Bakst moved on to work with various other theatre companies and costumiers. But it was Bakst who set the stage for the next branch of artists that came to work with Diaghilev, proving just how subversive, contemporary and magically escapist the ballet could truly be.

Leave a comment